By Isa Tousignant

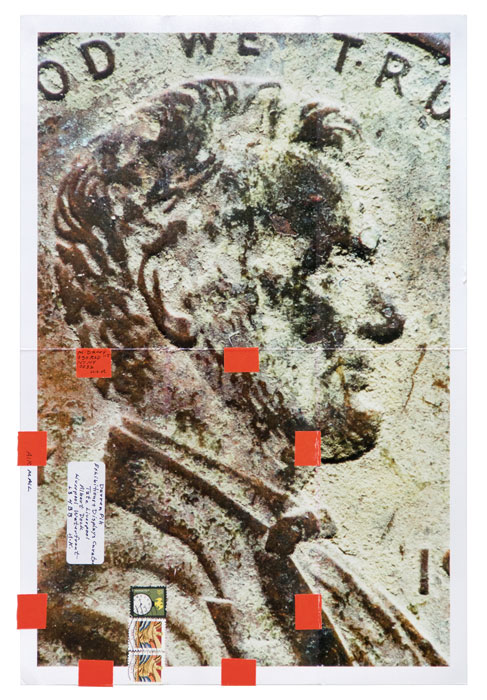

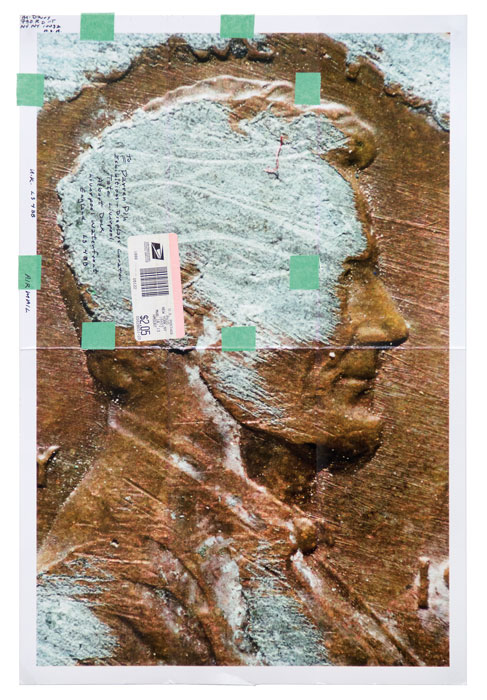

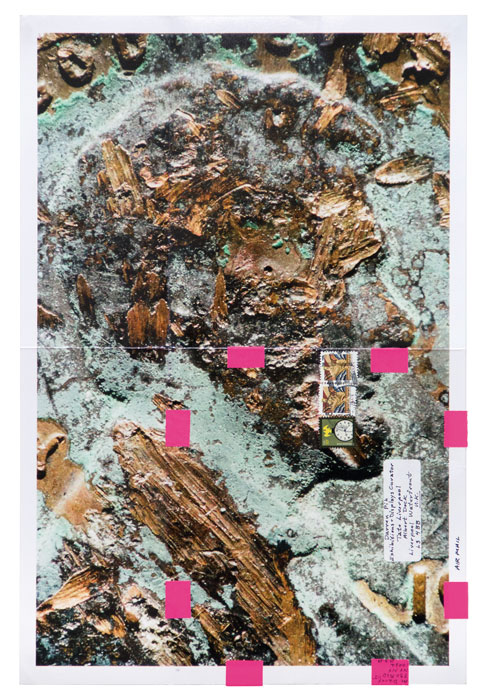

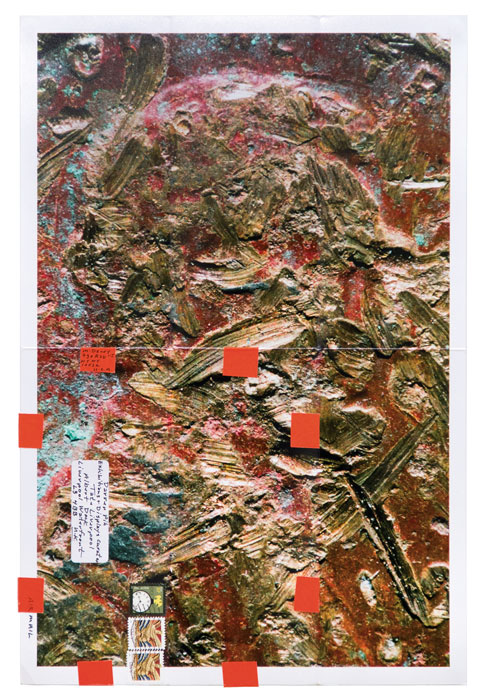

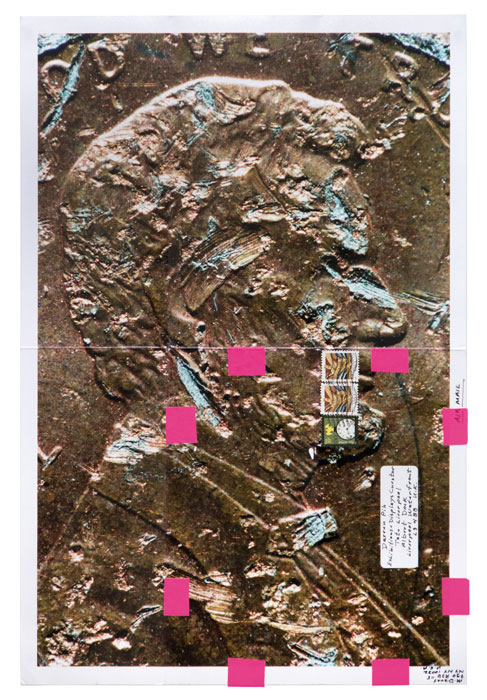

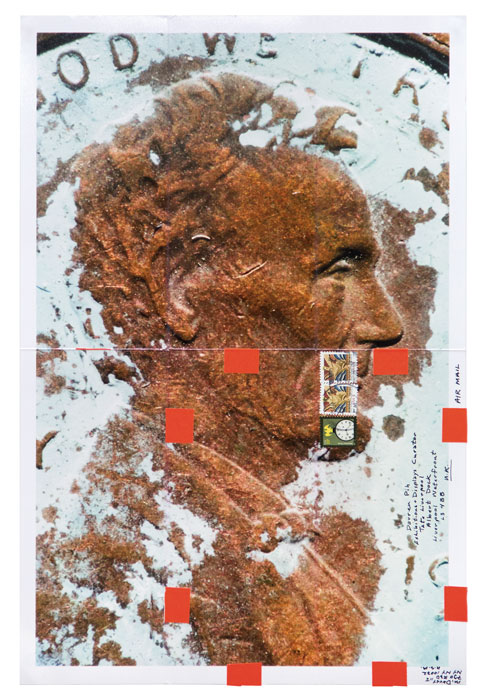

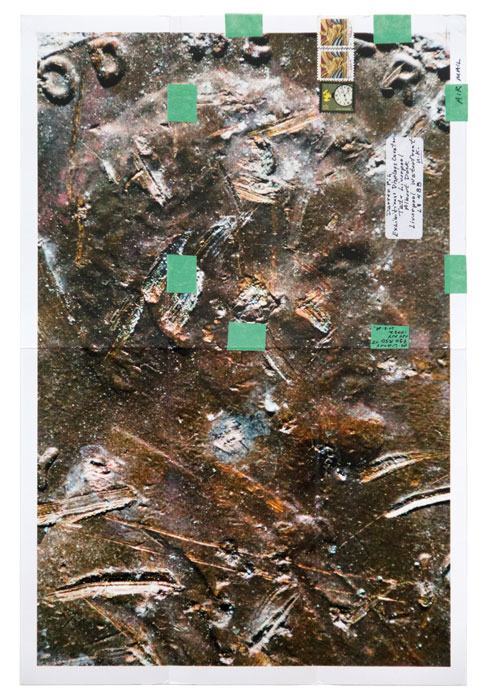

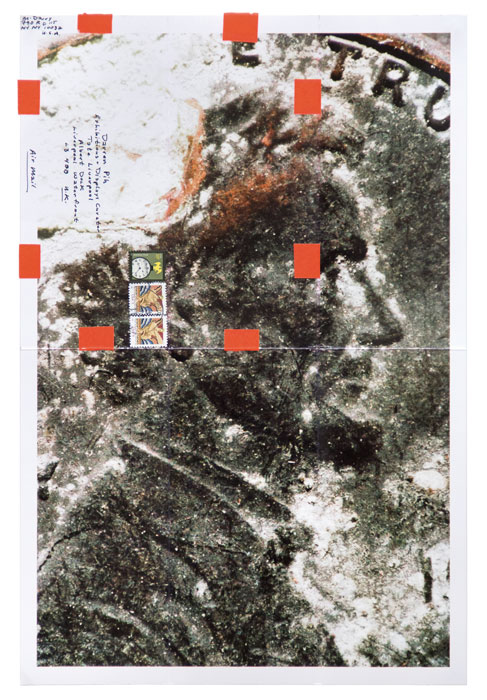

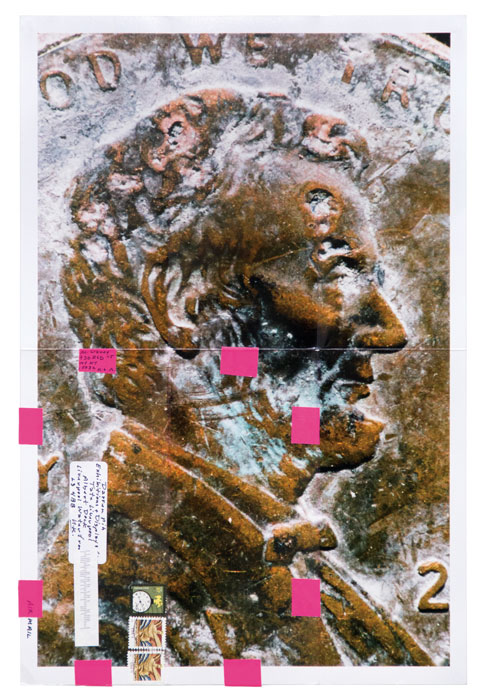

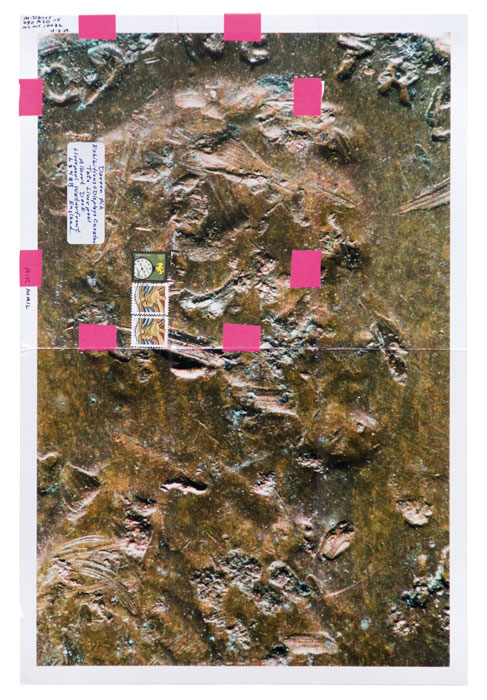

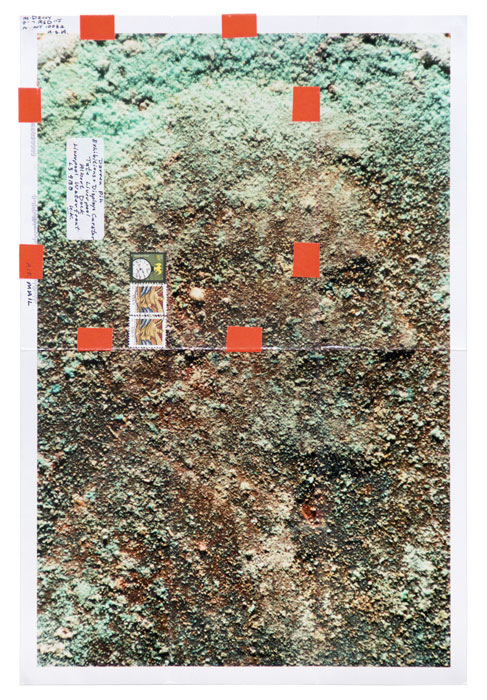

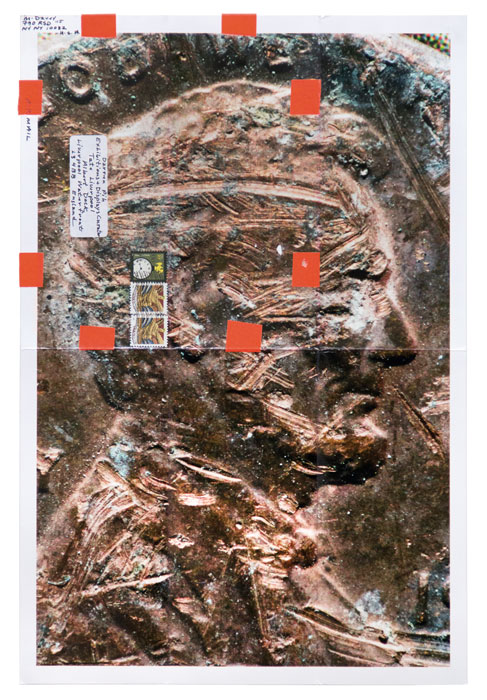

Moyra Davey’s Copperheads series has had a few existences. It was born in 1990, soon after the Canadian-born artist moved to New York, where she still resides. In those early days it was a project that lived a practically private life; after photographing Lincoln’s massacred head from the most age-ravaged pennies she could find, Davey kept her prints in a binder, at letter size, ready to be blown up to their intended 18″ x 24″ if purchasers or exhibitors showed interest. It was only nearly twenty years later, in 2009, that the entire series of one hundred photographs was exhibited in a grid formation at The Fog (now the Harvard Art Museum), in Cambridge, Massachusetts. By then, Davey had begun habitually mailing her work and exhibiting it with the traces of the transit, and so she did the same with Copperheads. The body of work has existed as such since, and expanded into other series of one hundred, with still more to come. Davey has never stopped collecting pennies.

Life is filled with discarded objects, moments, and thoughts, and those are the things that capture Davey’s attention. Her lens elevates the vernacular into the spectacular, whether it be words on a page, as in her Mary, Marie series, or photographs of her family members, in Les Goddesses. With a particular interest in little-known areas of history and unsung aspects of everyday life (the rudimentary process of mailing, for example, which touches upon ideas of exchange, travel, infrastructure, and accumulative mark-making, or the mundane world of economics, in its smallest and most insignificant form), Davey creates works that quietly infer profound thought processes. With Copperheads, the photographer, filmmaker, and writer became captivated by the signs of use on the lowly penny when she began researching eighteenth- and nineteenth-century misers, as well as Freud’s writings on money. Behind the images of scratched, corroded, etched, burnt, and petrified faces of the former president lies a heady mix of musings about the purpose and journey of money, and the ironic disconnect between its value and its devalued treatment. But the series also displays sheer sensorial pleasure, in the way that the copper plating warps in contact with the world, in the way that the photographs get marked in the mailing system, even in the way that the colour of the tape adds a graphic element to the assembled works.

I reached Davey in her New York home.

Isa Tousignant: You integrate a lot of material from the past in your work, whether it’s historical figures or images of your own family. Do you also have an interest in reusing past artworks of your own? Repurposing them to make new art? Moyra Davey: Oh yes, I do that all the time. Sometimes I’ll recycle images from the nineties, but more recently I’ve just started showing them as is. In a show I did in Vancouver I included five works I made in 1986, believe it or not. I like to do that, to connect things across decades. To feel that works from twenty years ago can still be part of a conversation with something I’ve just made, there’s something very pleasurable about that.

IT: What would you say is your relationship with time?

MD: I think it’s most people’s relationship with time! Especially as you get older, it gets more and more freighted; we’re always trying to be friends with time. But you have to work at it.

IT: What role does trace-making play in your work?

MD: It’s really important. The mailing process registers a lot of traces; the person it’s sent to, the postage. The photograph itself shows many marks of transit. They often get pretty scuffed up.

IT: Is there a reason behind the colours you choose for the tape that keeps the photographs folded through the mailing process?

MD: I have a palette of colours, and I always decide before-hand. In the case of these particular pennies, a lot of them were corroded and green, so I picked the pinkish hues to contrast with the green. But I actually use some green tape in that hanging as well. I’m still experimenting with the tape to see what works and what’s interesting. I’m still assessing how important the tape becomes as an abstract formal element on the surface of the print itself. You have this kind of pixel effect.

IT: In your writings about the series you mention an interest in misers, which I found fascinating. It got me wondering whether you were more fascinated by the idea of miserliness – having money and yet choosing not to spend it – than in poverty, or being frugal because of necessity?

MD: The interest in misers grew out of something very specific. When I first made Copperheads, I was doing a lot of work about money and I was reading up a lot about the psychology of money and Freud’s theories about money and anality, and I was pretty fascinated by all of that literature. Somehow I came across a book about eighteenth- and nineteenth-century misers, and my partner, Jason Simon, ended up making a film that was riffing off Erich von Stroheim’s film Greed – an epic 1920s silent movie about a miser. But to answer your question directly, I had actually never thought of the relationship to poverty.

IT: What led you down the path of study of psychoanalysis and money?

MD: Well, I grew up in Canada, and went to San Diego to go to UCSD, then ended up moving to New York with Jason, who was from New York. It was a whole new start: I’d just graduated with an MFA, I was in a new city, I was pretty broke, and I was thinking of what kind of work I would make. And I think because of the financial situation, money was the topic that was meaningful. It was related not exactly to poverty, but need. Financial need.

IT: Did moving to New York also affect your perception of consumer culture?

MD: As soon as I moved to the United States I could see the difference. There were hospitals that advertised – in Canada you would never see that! All the holidays here, Halloween, Easter, Valentine’s Day, every little holiday is an excuse to sell whatever you can sell. That was definitely an influence.

IT: Is there significance to the figure of Lincoln?

MD: Not really, he just happened to be the head that happened to be on the penny.

IT: So it would have worked the same with an image of the queen, if you’d done the series with Canadian cents?

MD: It would be different, with the queen . . . then you’d really be making a statement about colonialism or the empire. But no, in this case it was really about a psychoanalytic understanding of money. Freud believed that unconsciously we equate money with excrement – these dirty encrusted pennies simply summed that up. He brings it back to infancy, infants retaining their feces, or producing it for parents as their first gift to them. Think of the use of the concept of dirt as it’s associated with money in language: “filthy rich,” “filthy lucre,” “making a deposit” to mean relieving oneself; there are so many instances. Freud picked up on a lot of those. An obstinate, stubborn character is also connected to stinginess, seen as retentive, or anal . . . all of these kinds of things were what I was trying to figure out.

IT: Is there meaning to the number 100?

MD: No, it was just a dollar.

IT: Do you foresee further series?

MD: Yes, I’m doing more! I’m doing another hundred now, with another artist’s collection of pennies; and after I’ve done his, I’ve got another hundred of my own. It’s as if these dirty pennies are multiplying. It’s not like Canada here, where the penny coin has been discontinued; here they’re still minting them. Some of the ones I’m photographing now are from the fifties, but I also have a lot of really new ones that are completely messed up. I can just imagine kids in metal shops going at them. I like that idea.

Isa Tousignant is a contributing editor of Canadian Art and freelance writer on art, design, and lifestyle who cut her teeth as arts editor at an alternative weekly, back when cultural journalism still existed. She has dabbled in independent curating and helped create a number of art happenings, including the hostile takeover of a money-exchange centre by a dozen dissident artists. Her post-graduate research into the theme of animals in contemporary art and inter-species power dynamics has led her to become a born-again vegan. She lives and works in Montreal.

Over the past three decades, Moyra Davey (b. 1958, Toronto, Canada) has built an influential body of work composed of photographs, writings, and video. Recently Davey has had solo exhibitions at MUMOK, Vienna; ICA, Philadelphia; Camden Arts Centre, London; Tate Liverpool; Presentation House Gallery, Vancouver; Wilfried Lentz, Rotterdam; and Murray Guy, New York. Davey’s work was included in the 2012 Whitney Biennial and in the 2012 São Paulo Biennial, and is held in important collections such as the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Tate Modern in London.