By Érika Nimis

Lagos – Eko in the Yoruba language – is a typical megalopolis. With its some twenty million inhabitants, it is the economic and cultural heart and soul of Nigeria, which is the birthplace of Wole Soyinka (Nobel Prize for literature) and Fela Kuti (the father of Afrobeat) and the home of Nollywood (the third-largest movie industry in the world). “Lagos la mégalo,” a “centre of excellence” (according to the licence plates) is also a “capital of chaos, ” with its monster “go-slows” (traffic jams) and random brownouts that make the city the most plugged-in – to generators. One thing is certain: the hustle and bustle of the “capital of Africa” leaves no one indifferent. And so it is not surprising that Lagos has become a breeding ground for talents of all types.

In Lagos, the photography sector has seen an enthusiastic revival since the turn of the millennium; it seems that a new artist emerges every day (or almost), if one judges by the different spaces and events (art centres, galleries, festivals) devoted to the fixed image in this city that never sleeps. Nigeria is Africa’s most populous country, with a quarter of the continent’s population, and also its top economic power, due mainly to oil exports. As this economic prosperity, consolidated by relative political stability,1 has taken hold, photographic initiatives have proliferated. These initiatives are characterized by a spirit of very strong entrepreneurship, for, although the country is relatively wealthy, no government policy exists to support arts and artists. Thus, a few individuals (curators, patrons, artists), who have a wealth of experience abroad and hope to transmit their knowledge to the younger generations, play an essential role.

A Brief History. This new and burgeoning scene did not spring out of nowhere but is anchored in Lagosian history. A port city on the Atlantic Ocean, Lagos is connected to the rest of the world and has been open to photography since it was invented. It welcomed photographers passing through, then photographers who opened studios there in the 1880s – mainly on Lagos Island, where a community of repatriated “Brazilians” settled (following the gradual abolition of the transatlantic slave trade).

Starting in the 1920s, connections with Great Britain and the United States (where the élites went for their education) allowed for the emergence of a fertile photographic scene that claimed the “Stieglitz tradition.”2 Among the great figures in the history of Lagosian photography (in studio photography, art photography, and photojournalism) are Jackie Phillips, Billyrose, Peter Obe (whose photographs of the Biafra war were seen around the world), J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere, Tam Fiofori, and Sunmi Smart-Cole. Today, photography is, more than ever, a recognized profession, increasingly feminized, taught in university,3 and, better still, a means of expression that draws new practitioners.

2001: The Turning Point. Although the photography scene has always been dynamic in Nigeria, and particularly in Lagos, a turning point was reached in 2001 under the impetus of several photographers, including Akinbode Akinbiyi (based in Germany) and Don Barber, who guided the first steps of a new generation that soon organized into collectives. Depth of Field was the first collective to form, in December 2001, following the Bamako biennale. Some of its members (Uche James-Iroha, to mention just one) are now leading initiatives dedicated to photographic creativity and its dissemination throughout Nigeria and beyond.

Things accelerated in 2005, when the Goethe-Institut in Lagos hosted workshops, most of them run by Akinbiyi, leading to the creation of another important photographers’ collective, Black Box, from which emerged a number of confirmed talents who are known internationally today and are passing on their experience in their turn (Andrew Esiebo, Abraham Oghobase, Charles Okereke, Uche Okpa-Iroha).

Another important year for photography in Nigeria was 2007: World Press Photo’s Spot News award was given for the first time to an African photographer, Lagosian Akintunde Akinleye, who works for the Reuters Agency. The Centre for Contemporary Art (CCA) opened in Lagos, and it immediately threw strong support to contemporary creative photography. That year, Bisi Silva, the director of CCA Lagos – always ready to support the young generation from which she had come – was co-curator of the Rencontres africaines de la photographie in Bamako; eight years later, she was artistic director of the 2015 edition (October 31 to December 31). Located in Yaba, not far from the University of Lagos, CCA Lagos encourages the development of critical thinking among young artists and cultural actors by programming exhibitions, discussions, seminars, and workshops.

2010: Things Move Quickly. In 2010, Silva started an original training program, later named Asiko Art School.4 This thirty-day workshop in residence continues to take place every year in a different African art capital (Dakar in 2014, Maputo in 2015).

Silva is also interested in constructing a historical discourse on photography and, more generally, art practices in her country (and the entire continent). Recently, she edited a magnificent monograph, produced completely independently, on the Nigerian photographer J. D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere, who died in February 2014, and who was known internationally for his series on women’s hairstyles.5

Returning to 2010, when the Asiko program was launched, it was also the year that LagosPhoto, the first international-scale photography festival in Nigeria, was launched. The festival ran a summer school in partnership with a German school, the Neue Schule für Fotografie in Berlin. LagosPhoto is organized by the African Artists’ Foundation (founded in 2007), directed by Azu Nwagbogu. It takes place every October in spaces mainly on Ikoyi Island and Victoria Island (wealthy districts of the city), at the Eko Hotel (the festival’s headquarters), and in art galleries, among them Omenka and Art Twenty one. In parallel to these initiatives, which provide visibility to the local scene, a market – still fragile – is emerging as collectors who used to purchase paintings are now, quietly, turning toward photography. But it is still outside of Nigeria that artists gain their reputation.

Lagos: Primary Source of Inspiration. All photographers based in Lagos have the city on their minds and in their eyes. It is impossible to escape. Some, witnessing daily life, try to capture the city’s quirks and transcend them; Charles Okereke,6 for instance, became known for his series Canal People and Unseen World on the dreamlike microcosm of trash. In the series Homecoming, he takes a look, both concerned and detached, at certain alarming effects of the unmanageable overpopulation in Lagos – which attracts more migrants every day to what they assume will be their El Dorado – precarious jobs, interminable go-slows, pollution, and more.

Andrew Esiebo is updating the documentary genre in the era of Instagram (a network on which he is very active) by focusing on a society that, although quite dysfunctional, generates each day models of resilience, invisible heroes. In Who We Are, he presents members of the gay community where they live, very simply, to silence the prejudice and discrimination from which they suffer. In his most recent series, such as Transition, he takes an unblinking look at social, economic, and urban transformations that are sweeping through the most populous city on the continent.

Adolphus Opara is also interested in the uncertain fate of the marginalized communities of Lagos. In his series Shrinking Shores, he portrays how these communities are suffering the full brunt of the effects of globalization and dependent on an increasingly threatened environment on the shore of the Atlantic Ocean. Like Esiebo, Opara photographs as a storyteller, in the hope of raising awareness.

Other photographers redesign the reality of Lagos through mises en scène to better point out its problems. Since he returned from the United States in 2005, Ade Adekola has been conducting a visual reflexion on Lagos, through which millions of anonymous people transit daily – men and women struggling to survive. He transforms them into “icons” of modern times through a solarization effect, and transposes them into Western urban scene “postcards” in a series titled Ethnoscapes – Icons as Transplants.

A former member of the Depth of Field collective and director of Photo.Garage,7 Uche James-Iroha became known internationally for his series Fire, Flesh and Blood, for which he received an award from the Prince Claus Fund in 2008. In his most recent series, Power and Powers, he challenges, in settings that are highly charged – almost apocalyptic – in highly contrasting black and white highlighted with a few touches of colour, the harmful links that tie political powers to the (poor) management of electricity in Nigeria.

Transcending Outer and Inner Chaos. All of the photographers mentioned here have in common the desire to decipher “planet Lagos” and its permanent chaos in images. Some do this through performance and self-fiction.

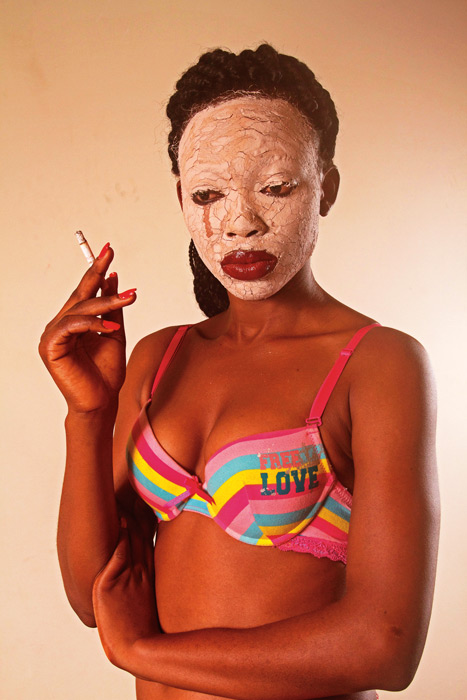

Chriss Aghana Nwobu, a founding member of the Invisible Borders collective,8 defines himself as an experimental, unclassifiable, multifaceted artist. Through fashion photography, portraits, and photojournalism, he tries to convey emotionally what he captures from the world around him. In the series Masked Burden, he photographs women of different ages and with various careers, their faces covered with a white mask that cracks, allowing the weight of suffering and unsaid things of an entire society to emerge.

A member of the Black Box collective and director of the Nlele Institute,9 Uche Okpa-Iroha first became known for his series Under bridge life, Grand Prix Seydou Keita 2009. In The Plantation Boy, (2012), again Grand Prix SK en 2015, Okpa-Iroha, now practising self-fiction, inserted himself into a masterpiece of world cinema, Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather (1972), in a firm desire to rewrite not only the history of the cinema, but history writ large.

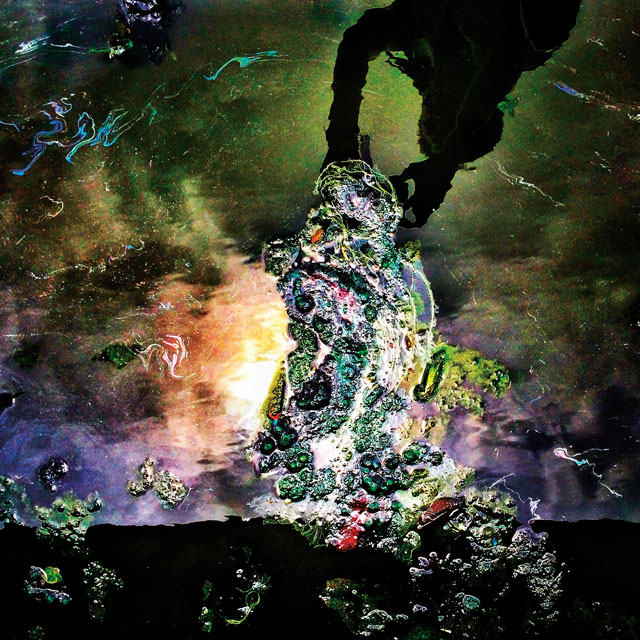

After meeting with the artist Delphine Fawundu (Brooklyn) in 2012 during LagosPhoto, Adéola Olagunju unleashed her creativity; she produces images through not only photography, but also painting and collage on paper. A member of Invisible Borders, she first came to notice for her performance on the city (Resurgence: A Manifesto). In Beautiful Decay, a continuing series, she shares her fascination with how things decay by casting a reflective gaze on the ephemeral – in particular, the garbage filling Lagos’s waste channels.

Abraham Oghobase has also made Lagos his site of performance; in Untitled 2012, a series for which he was nominated for the Prix Pictet, he underlines that battle that each individual in the city undertakes to preserve his or her private – and commercial – space by conducting what is literally “guerrilla marketing,” to judge by the thousands of messages anarchically flooding the walls of Lagos. Oghobase, also a member of the Nlele Institute, was, in September 2015, co-curator with the video artist Jude Anogwih of the first edition of Lagos OPEN RANGE, presented at the Goethe-Institut with the support of the CCA, Lagos. Among the artists with works in this event, Aderemi Adegbite stood out with a series, Time-out, that revisits his own history through digital manipulation of family photographic archives, into which he inserts himself through a double-exposure effect, as if to exorcise his personal demons.

In the “laboratory of the impossible”10 that is Lagos, a megalopolis of incredible vitality in which everything dies and is quickly reborn, photography has a past, a present, and especially a future. And if the competition there is rough, the local scene is developing and always attracting recruits fascinated by the infinite possibilities that the medium offers in the digital age. In Lagos, photography always makes people dream.11

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 Y. Ogunbiyi, “Introduction,” The Photography of Sunmi Smart-Cole (Lagos: Daily Times of Nigeria LTS, Ibadan, Bookcraft, 1991), xiii. This text is a reprint of an article that originally appeared in The Guardian (January 15, 1984).

3 Universities (such as those in Zaria and Nsukka) and the Yaba College of Technology in Lagos, and even the Nigerian Institute of Journalism have never adequately valued the teaching of photography, even though – good news – the University of Port-Harcourt soon plans to open a photography section named for the first Nigerian photographer, Jonathan Adagogo Green (1873–1905), who was born in the region.

4 See http://www.asikoartschool.org/.

5 Bisi Silva (ed.), J. D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere (Lagos: CCA, 2014).

6 With his wife, poet Tobi Ilori, Okereke mounted an educational and ecological project, the Alexander Academy of Arts, Design and Alternative Methods. Situated in Badagry, an hour away from Lagos by road, far from the pollution and stress, this project, which is an invitation to decentralize art, is financed entirely (for the moment) with personal funds.

7 Uche James-Iroha founded Photo. Garage as a space for exchanges, open to all photographers, amateur and professional. With a studio with a large-format digital printer, a residence, and a gallery, it also serves as a site for encounters and is known for its passionate debates on society and politics.

8 As are Uche Okpa-Iroha, Uche James-Iroha, Charles Okereke, and Adéola Olagunju. For more about Invisible Borders Trans-African Photographers, initiated by the photographer Emeka Okereke and presented at the 56th Venice Biennale, see http://invisible- borders.com/.

9 The Nlele Institute African Centre for Photography is a non-profit organization whose objective is to professionalize short (workshop) programs and longer ones (that might last a year) for new generations of photographers. The Nlele Institute is currently collaborating with the Goethe-Institut to open an independent space for research and creativity on urban cultures on Lagos Island.

10 To use the term of journalist Jean-Philippe Rémy in Le Monde, March 27, 2015.

11 I would like to thank everyone who opened the doors of Lagos to me – in particular, Andrew Esiebo and his brother Mamus, Taiye Idahor, Lucille Haddad, Charles Okereke and his wife Tobi Olori, Jelili Atiku, Uche James-Iroha, Moïse Gomis, Abraham Oghobase, Adolphus Opara, and, last but not least, Bisi Silva.

Érika Nimis is a photographer (former student at the photography school in Arles, France), Africa historian, and associate professor in the art history department at the Université du Québec à Montréal. She is the author of three books on the history of photography in West Africa (including one drawn from her doctoral dissertation: Photographes d’Afrique de l’Ouest. L’expérience yoruba [Paris: Karthala, 2005]). She contributes to a number of magazines and founded, with Marian Nur Goni, a blog devoted to photography in Africa: fotota.hypotheses.org/.

Photographers’ websites:

www.abrahamoghobase.com/

adeolaolagunju.com/

aderemiadegbite.com/

www.adolphusopara.com/

www.andrewesiebo.com/

charles-okereke.blogspot.ca/

theplantationboy.blogspot.ca/

www.iconsofametropolis.com/

Websites related to this article:

www.ccalagos.org/

www.lagosphotofestival.com/

tniacp.org.ng/

www.goethe.de/ins/ng/de/lag.html?wt_sc=nigeria

www.art21lagos.com/

www.omenkagallery.com/

www.africanartists.org/