By Jill Glessing

Despite their great diversity in culture and geography, the countries of Latin America share inextricable ties with Europe forged by the Iberian incursion. Columbus’s navigational confusion instigated centuries of bloodletting that passed through what Eduardo Galeano has called “the open veins of Latin America.” After these countries gained political independence, the relations between colonizer and colonized began to change. Today, as Latin American economies continue to ascend relative to crisis-crippled Europe, immigration and cultural exchange are becoming mutual.

Emblematic of this intertwined history was this year’s Latin American focus for PHotoEspaña, the Madrid-based international festival of photography and visual arts. In 2014, the festival’s curatorial format shifted to a regional focus, inaugurated with a program of Spanish photography; next year, the spotlight will be on Europe.

PHotoEspaña’s increased presence in Latin America – particularly through its Transatlántica program, which offers portfolio reviews and exhibitions for emerging artists – makes its commitment this year a natural development. Forty-eight of the sixty-nine exhibitions spread across Madrid’s public and private art spaces, in addition to fifteen international venues in places such as Bogotá and Paris, reflected the complex, and often difficult, history and conditions of Latin America.

The “New World.” Photographic technology came too late to capture Columbus’s first glimpses of America; only through the imaginary can that fateful voyage be represented. Polish photographer Janek Zamoyski, in his exhibition Heave Away at Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, sailed the sea steps that moved the navigator toward his second encounter with what Europeans considered a new world. The empty and open sublimity expressed in Zamoyski’s twenty-one seascapes, each of them representing one day of the conquistador’s voyage, both belie and forecast the intense and churning history that would follow.

Desire for control of the trade with Asia prompted the Europeans’ exploration. But what was discovered proved far more profitable: rich resources extracted by indigenous labour and new souls for their Christian god. The racism that justified both kinds of thefts, the heritage of which exists today in complex racial divisions, is apparent in the photographic archive of the Salesian Apostolic Vicarship in the Ecuadorian Amazon. In the Eye of the Other Historical Photography of Ecuador: Breaking into the Amazon, at Círculo de Bellas Artes, presented vintage and contemporary prints from these archival glass negatives. On display were conventional frontal and profile ethnographic shots of naked Amazonians, such as the Shuar-Achuar people, and group portraits of paternalistic missionaries and rubber-plantation managers surrounded by child-like natives. The colonized were photographed performing traditional rituals and new European ones: mourning their deceased within Christian ceremonies, kneeling in prayer wearing crucifixes; and collecting in curiosity around the instrument that documented them – a large camera on a tripod.

Colonial photographers such as Manuel Jesús Serrano, who made some of the images above, conformed to Eurocentric perspectives. When indigenous people gradually got behind the camera, their images began to reflect their own interest (a process that young Latin American photographers are still engaged in today). Between 1920 and 1973, Martín Chambi, a Peruvian Mestizo, worked as a studio, landscape, and documentary photographer in Cuzco and the surrounding highlands. Chambi is celebrated for his gentle melding of European aesthetics with his own culture. Seeing twenty-five of his images, beautifully printed from original glass plates by the Madrid photographer Castro Prieto, was thus a highlight of the festival for me. (Prieto’s re-photographs made in Cuzco were paired with Chambi’s original images at the Museum of Anthropology in Martín Chambi – Perú – Castro Prieto.)

Chambi excelled at manipulating natural Peruvian light at a time when artificial studio lighting had not yet reached outlying areas. He made use of remarkable Rembrandt-style chiaroscuro to model his bourgeois and Indian subjects alike. Outstanding is Wedding of Don Julio Gadea of Cuzco (1930) in its expression of pictorial depth through fathoms of blackness out of which floats a white veiled bride and her coterie.

In the 1930s, revolutionary movements were sweeping through South America, and traces of this spirit might be discerned in Chambi’s warm and sensitive portraits of ragged campesinos with whom he shared the Quechua language, but who, unlike him, served at the bottom of society as indentured labourers in mines and haciendas. Chambi’s images of Machu Picchu were also thrilling, both for their pictorial beauty and in the knowledge that he was among the first to photograph the Inca ruins.

Modernist Visions. Much exhibition space was given to early- to mid-twentieth-century Latin American photographers. Among them were two women photographers whose work has largely been neglected by modernist avant-garde and formalist canons,

Tina Modotti and Lola Álvarez Bravo, both of whom were engaged in the Mexican cultural revolution in the 1920s and 1930s.

Upon arriving in Mexico in 1923 from the United States with Edward Weston, Modotti, after connecting with the political and arts intelligentsia, became active in Mexican indigenous movements and the Communist Party. Her increased engagement with the latter led Modotti to abandon photography and, in 1929, to her forced exile from Mexico. It is this central bit of biography that made this exhibition venue – the gallery in Loewe’s high-end handbag shop – an awkward fit. Produced in just six years, the work presented here expressed her deeply political and sensual signature.

Her range of genres was shown through fifty vintage silver prints, as well as warm-toned platinum prints that softened her formalist experiments. The abstract approach, filtered down through Weston’s Group f/64, used in Modotti’s still lifes (of lilies, cacti, and telephone wires) bleeds softly into her images of indigenous subjects: the circles of sombreros under which campesinos peruse political newspapers or march in protest, the creased bums of babies settling onto their mothers’ hips, worn hands resting on a shovel or scrubbing clothes, and a revolutionary composition of a Mexican guitar, sickle, and bandolier. Looking away from hard-edged formalism altogether is Roses (1924); languishing within its frame are soft heaps of petals folding and falling over themselves.

Also exhibited were government-commissioned photographic documents of post-revolution frescoes by Mexican muralists, including Diego Rivera. After Modotti’s deportation to Berlin in 1930, both her camera and her position were passed on to Lola Álvarez Bravo. Like her predecessor, Álvarez Bravo was trained, and overshadowed within photography canons, by her partner – in this case, Manuel Álvarez Bravo. Her comprehensive solo show at Círculo de Bellas Artes, Photographic Collection from Fundación Televisa, thus offered a rare opportunity to see her work. Like Modotti, Álvarez Bravo worked across commercial, journalistic, and art genres, but with a greater interest in surrealist street photography and a more limited political commitment. Striking were constructivist-style abstract street compositions, such as the silhouetted figures on metal steps (Some Climb and Others Descend, c. 1940) and charming street photography moments emerging from the deep shadows cast by Mexican light. These latter showed the influence of Henri-Cartier Bresson, whom Álvarez Bravo photographed during his visit to Mexico, the results of which are included here.

At Museo Lázaro Galdiano, the exhibition My Beloved Mexico illustrated the mutual influence between Mexican and American photography. Twenty-one works by such Mexican photographers as Manuel Alvarez-Bravo and Graciela Iturbide, as well as American straight photographers such as Paul Strand and Edward Weston, were followed by twenty-eight images by Manuel Carrillo. The Mexican photographer’s black-and-white images express great warmth for his subjects – indigenous people, children, and animals – embraced by dramatic Mexican light and solidly structured within formalist composition.

Cracks in the Colonial Legacy. Colonial independence, achieved by many Latin American countries in the nineteenth century, didn’t end the pattern of repressive regimes; they were perpetuated up to the late twentieth century by U.S. foreign policy, which sought full influence in the region. Although democratic political forms developed in response to social movements and political unrest, the warmth that they injected into society soon dissipated when these “new democracies” became the first testing grounds for neoliberal policies. The growing disparity between ruling and marginal classes created a huge underclass, populated largely by descendants of indigenous peoples, who had to fend for themselves through drug trading, prostitution, and perilous attempts at migration.

Contemporary photographers have been preoccupied by these traumatic conditions, and by concerns about race, identity, and gender. In six big group shows, each one organized around a different perspective, hundreds of works made by Latin American artists during the last several decades explored such issues, increasingly within concerns with form, technology, and aesthetics.

At CentroCentro Cibeles, Latin Fire: Other Photographs of a Continent 1958–2010 presented Anna Gamazo de Abelló’s collection of Latin American photography. The titular “fire” refers to the passion that has been rippling through the subcontinent in favour of political, social, or sexual rights and expression. Images of authoritarian state police powers and street protests and violence in response to them predominated. In one image made in 1966, soft Venezuelan rainforest light filters down on a group of guerrilla fighters as they pause to pose for Mexican photojournalist Rodrigo Moya; in Alberto Korda’s Quixote on Lamppost (1959), a sole individual perches comfortably above, overlooking swells of post-revolutionary Cubans compatriots.

Strongest among the group shows was Revealing and Detonating: Photography in Mexico, ca. 2015, also presented at CentroCentro Cibeles. A large selection of the most sophisticated contemporary works by both Mexican and visiting artists dealt with topics of violence, social and economic inequality, and cultural and gender identity. Among these concerns, the land figured prominently, for its own condition and its metaphoric value.

In 2014, an earthquake tore open a massive rift in the Mexican landscape. Delivering this image of a Mexico undergoing tumultuous upheaval were two dramatic colour photographs of the ominous opening by Juan Carlos Coppel, titled The Fissure (2014). Oscar Farfán guides us to the land that swallowed the blood of innocents. His series Scorched Earth (2009) documents sites where the Guatemalan military inflicted terror to eradicate over four hundred indigenous communities due to their presumed alliance with terrorists. The mute landscapes in two large colour photographs, Cajixay and XIX, speak only through the texts that accompany them – survivors’ transcriptions describing the atrocities and loss that occurred there. In Ray Govea’s large colour photographs Gravedad Arterias (2012), the land itself is destroyed, its pain revealed though shimmering toxic glows signalling the chemicals, including cyanide, that had been dumped there.

Like the land, the faces of those who have lost their daughters and mothers – the disappeared women of Ciudad Juarez – are etched in pain. Maya Goded has spent much of her career – risking her own life – documenting the many Mexican women who work in prostitution in the violence and machismo of the border towns. Many go missing. To powerful effect, a dual video projection on either side of a corner shows long quiet shots of the sun-beaten land, littered with debris and grazed by dry breezes, where her subjects dwell. Breaking up the bleak landscapes are sections in which young girls (perhaps daughters of disappeared mothers?) speak softly to the camera, and mothers stand weeping in cemeteries, whipped by arid winds.

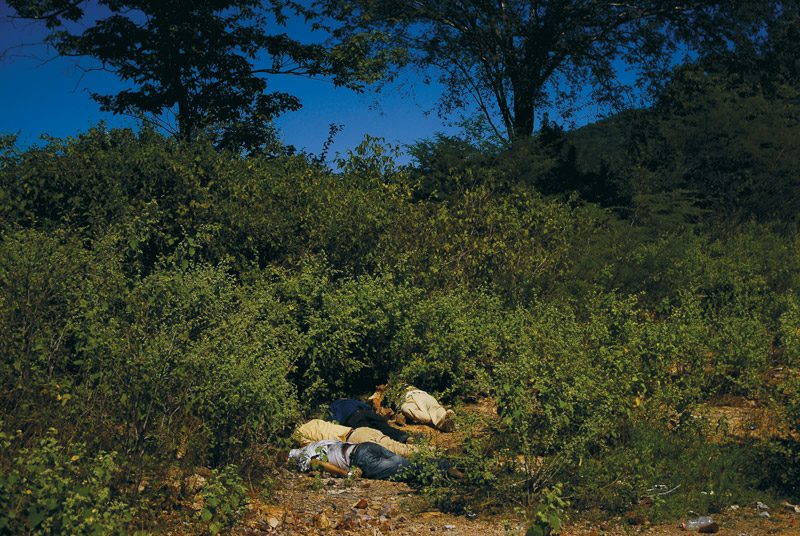

Showing another side of chronic poverty in Mexico are images related to the drug trade: gangs, brutal murders, and police raids. Photojournalist Fernando Brito documents, in the stark style of Weegee, the murdered bodies found brutalized and dumped in woods and on roadsides. Pieces from his series Your Steps Were Lost in the Landscape, Culiacán, Sinaloa (2006) were shown here.

Very different in tone is Luis Arturo Aguirre’s series Undressed (2011–13). Each of the closely framed vertical portraits presents a young male transsexual, posed prettily against vivid candy-coloured backgrounds. The boy–girls are sweet and slender, coiffed and pouting, with innocence or glamour, at the camera, in an array of iconic types of feminine seductiveness.

Two mature artists with polished bodies of work were given deserved tribute in their respective solo shows. Ana Casas Broda is a Spanish artist currently residing in Mexico (and co-curator of Revealing and Detonating, discussed above). In Kinderwunsch, at Círculo de Bellas Artes, Casas Broda conducted a profound exploration of body and psyche, amorphously sliding between states of adulthood and childhood. Photographs, diaristic text panels, audio, and video wove a narrative that shifted seamlessly from the artist’s dark descent back to memories of her troubled childhood, her desire to have children (Kinderwunsch), and her role as a mature and loving parent. Many of the photographs are styled as secular Baroque paintings, in their large size, chiaroscuro, and richness in drama and colour. A looped, red-toned video projection covering two full walls of a darkened room shows a mother bathing her infant. The accompanying sound of tender cooing is a deeply moving evocation of mother-and-child intimacy.

This sampling of the 18th PHotoEspaña can conclude at no higher a point than with the Guatemalan-born Luis González Palma and his Constellations of the Intangible at Espacio Fundación Telefónica. This seasoned artist engages in themes that cut across Latin American photography – in particular, indigenous heritage, colonial violence, and post-colonial identity. But he melds these subjects within highly sophisticated explorations of historical, and often Western, visual technologies, aesthetics, and genres.

Many of his images present a face that looks directly out at the viewer. But unlike the Mona Lisa, whose eyes seem to benignly follow its viewer, his indigenous subjects force a confrontation with a murderous colonial past. Faces shine out from a catoptric mirror, an anamorphic optical device of the style explored by Leonardo. A photographic face – stretched, distorted, and circling the base of a central silver cone – is brought under rationalist perspectival control when reflected in the mirrored cone. Which has the greater hold on reality – the scattered photographic face or its image in its curved reflector? Identity, particularly for indigenous peoples, is slippery and ephemeral.

Faces also emerge printed on the large rolled surfaces of brown-toned felt. Red thread is sewn into some of their surfaces, sometimes dangling loose, suggesting centuries of blood lost through open veins, and the constant stitching and suturing that continues to be necessary for any perception of Latin America.

Jill Glessing teaches at Ryerson University and writes on visual arts and culture.