So pervasive have the interventions become that they challenge the stereotype of nature as an ongoing and seemingly inexhaustible eternal backdrop to all that we do. Our era is all about the intertwining of the human built landscape and the natural world. It is what we now call the Anthropocene, an era in which humanity activates and impacts Earth’s climate and ecology as it never has before. Geneviève Chevalier’s Montreal exhibition My Woodland, phase II is conceived like a developer’s project presentation. The difference here is that nature is presented on an equal footing with the developer’s omnipresence and with a sublime sense of mimicry. The artist addresses those touchy human-built interventions at the edges of cities, in historically significant places and parks, and, in the case of the island of Montreal, even in newly built suburbs. Development impinges on so-called pristine, untouched nature reserves and green spaces in the urban environment.

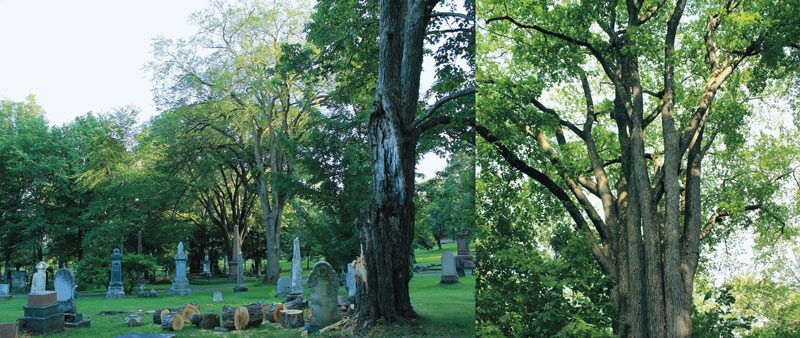

Sillery, Quebec, is a case in point. Sillery was the focus of Chevalier’s My Woodland, phase I, presented at La Chambre Blanche in Quebec City as part of Manif d’art in 2014. Like My Woodland, phase II, My Woodland, phase I addressed development in the historical green space near Sillery and in nature preserves – in this case, Boisé Woodfield, located in the historical district of Sillery adjacent to the St. Patrick cemetery. Sillery was settled under the French regime, and this wooded area had three-hundred-year-old trees still standing as recently as 2015. Protests by scientists, ecologists, and residents were to no avail as the Quebec provincial government finally approved a construction project in Boisé Woodfield. Leading in to Quebec City, Sillery and the Boisé form a beautiful historic suburb that is now increasingly encroached upon, as Chevalier’s documentary-style photographs of apartment buildings in the making show. At the Quebec City venue for My Woodland, a recorded interview with Marilou Alarie embroiders on the recurring theme of displacement of nature sites “for the view” or access to nature. Alarie discusses a development at Forest des Hirondelles near Saint-Bruno-de-Montarville.

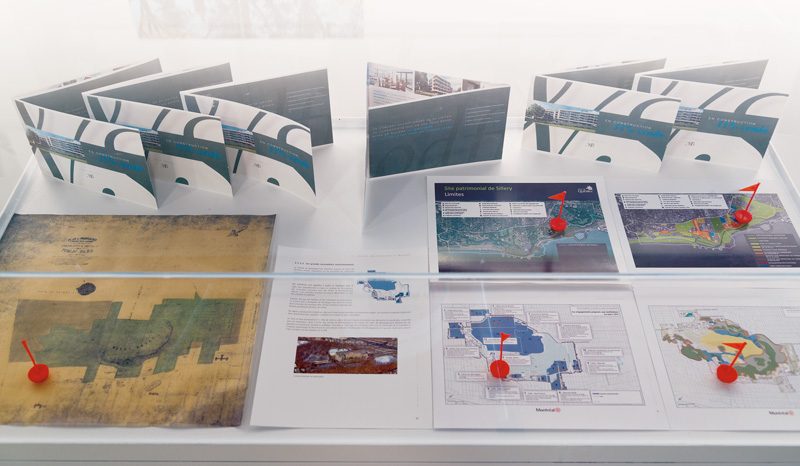

The scale of Chevalier’s My Woodland photographs at the Maison de la Culture Notre-Dame-de-Grâce in Montreal is approachable and human. There is no conceivable barrier between us – the viewers – and the woods that she presents. Her lightbox series has a presentational format resembling advertising, but the language of imagery is of our times and what we are used to. It is neutral, undramatic, nearly insignificant. A series of small-scale photos has a walk-about feel – as if we were actually walking the woods, even though we can see the occasional sign. Signs in nature! What an anomaly! And what a sign of the times! Some of the trees are spray-painted and marked for cutting or marking. Marking becomes a form of ownership, just as Aboriginals marked trees to suggest points of reference in a landscape. In one of the “showcases” we even see tiny maps and overviews – some of it green space, and some of it city. A red plastic flag becomes a whimsical point of reference. The red flag designates nature, something contrary to a developer’s project. Maps and a video of still images of the former seminary of the Priests of Saint-Sulpice next to Mount Royal in Montreal show another example of a heritage site just outside a protected nature area, on Cedar Avenue in Westmount. The developer of luxury condos at this site has built fences around an area of forest previously accessible to the public. Here again, Chevalier is bringing art into the political realm, making it a forum for discussion and awareness of nature displacement of which we are seldom aware.

Another of the show’s Plexiglas presentation boxes has earth and growth in it – like a miniature Walter de Maria Earth Room or a Land Art maquette. This “model,” like the photographs and the other visual elements and objects in the show, prescribe how we assess visuality and imagery. The art, like its subject – nature – becomes commodified by its conception and presentation. The artist’s emphasis is less on experience as a direct phenomenon than on conception and presentation – as quantifiable and measurable as this box of earth!

With My Woodland, Chevalier suggests that our ideas and expectations are likewise quantified and mediated by what we are made to expect through repetition and mediation of desire. Our perception of the land and of place is what Paul Virilio has called the “sudden cybernation of geophysical space and its atmospheric volume.”1 As real-time experience is transmuted by data-transfer systems, spatial mobility becomes a place of reference, and it supplants the stationary or the permanence of a land or cityscape or the details therein. A series of green bouquet ribbons presented in another Plexiglas presentation box is, like the prize ribbons for cattle at an agricultural fair, a symbolic signal of a “successful” real-estate sale, or it could be a “welcome signature” placed on the door of the real-estate “object” that the latest buyers have purchased.

Then there are the more subtle images of forest in the show. Trees become a screen through which we can see the outlines and silhouetted structures of apartment buildings. The forest begins to feel like a veil that gives way to open fields with fewer trees surrounding the buildings. The trees exist as photographs in a design-like relationship with the overall exhibition space. A soundtrack recorded in Mont-Orford National Park adds a background aural environment replete with bullfrogs, birds, and other nature sounds. There is a sensitivity in the way that Chevalier’s artwork represents a “total artwork” (part of an overall theme and process that has traversed all of her projects to date) and a public gesture of recognition of the actions, strategies, and programs that developers use and abuse each and every day. These artworks do not dominate the exhibition space, but are merely elaborated in the space, as if proposing a dialogue between the image and the physical reality. A tension is inherent to this neutral yet dualistic dialogue on image and reality.

If anyone could critique My Woodland as a presentational art piece, it is for its very neutrality, its hands-off documentation of the invisible, ever-evolving tragedy of unregulated

development in cities. This development eventually gives way to a kind of chaos, in which the history of development, of culture, of the people who preceded it all, is ultimately erased, wiped out, aside from the occasional memento house, church, and street. The art in My Woodland is less about the photograph as document, and more about the presentational mode. The museum-like presentation, like all presentations – including those of real-estate developers – is the art, and it says much about the gap between reality and fiction, expectation and realization.

Part fiction and part reality, My Woodland plays on the gap between illusion and reality, in which developers, governments, and profiteers build a paradigm of expectations never realized, but always in opposition to the status quo, to what is there, to the nature that is a part of our global culture. These are the tensions that Chevalier seizes on – the actions that occur invisibly, changing the landscape, the cityscape, until it is too late, and later forgotten. While the permanence of a tactile and physical nature can seem real, it exists only if the mindset of the public is there. Value is contained, sequestered, set apart, as if we were not living at all, but participating in an image quest. And yet the physical, tactile, real world reacts to our interventions, our tampering with ecosystems; it does not challenge our ideologies, but simply reacts in its preternatural and chaotic way to what we are doing to the living world that we are a part of.

Artist and independent exhibition curator Geneviève Chevalier has presented her work in Quebec, Ontario, and abroad. She has completed a doctoral dissertation on the practice of situated curatorship and exhibition as mechanism for public debate. Currently, she is a lecturer at UQAM and postdoctoral fellow at the École de l’image of the Université du Québec en Outaouais. She was previously co-conservator at the Foreman Art Gallery at Bishop’s University in Sherbrooke. Born in Quebec City, she lives and works in Eastman, in the Eastern Townships. genevievechevalier.ca

John K. Grande curated Earth Art for the Pan Am Games (2015) and Merano Nature Art Spring 2015 in Merano, Italy. His most recent publication is Nils-Udo, sur l’eau (Arles: Actes Sud, 2015).