Par Zoë Tousignant

Canadian photographic art was not born in the 1970s. There is evidence that photography was in use here as an expressive form, by professionals and amateurs, throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.1 Through such outlets as exhibitions, salons, books, and periodicals, artists and other practitioners in Canada were both aware of and actively contributed to the development in photographic aesthetics that was occurring internationally. Nevertheless, the 1970–90 period was a time of particular growth in Canada – a time when a great number of photography-centric institutions were created and the discourse on contemporary photography emerged.

The process of institutionalization – but also simply of popularization – of the medium had begun gradually in the 1960s, chiefly through the activities of the National Film Board of Canada’s Still Photography Division (NFB/SPD), which from 1960 to 1980 was headed by Lorraine Monk. The NFB/SPD’s regular organization of travelling exhibitions, acquisition of contemporary photography, and production of photography books gained momentum with the approach of the 1967 centennial celebrations.2 Acting as both an inspiration and a counter-model for future photographic institutions, the NFB/SPD was crucial in helping to define the very notion of “Canadian photography.” As the 1960s drew to a close, signs that such a blanket notion had its limitations began to appear in the discourse, with regional distinctions such as “Quebec photography” and “Western Canadian photography” being affirmed with increasing force.

The 1970s and 1980s saw the establishment of a multitude of local photography-oriented institutional entities that included commercial galleries, artist-run centres (or parallel galleries), associations and groups, museum collections, and periodicals. Many did not last beyond the 1980s, and those that did have done so mostly with slightly adapted, broader mandates – a fact that contributes to the sense that these two decades were a self-contained moment of glory for the practice of photography in Canada. It was a time when it was widely believed that photography needed its own, medium-specific institutions in order to thrive here.

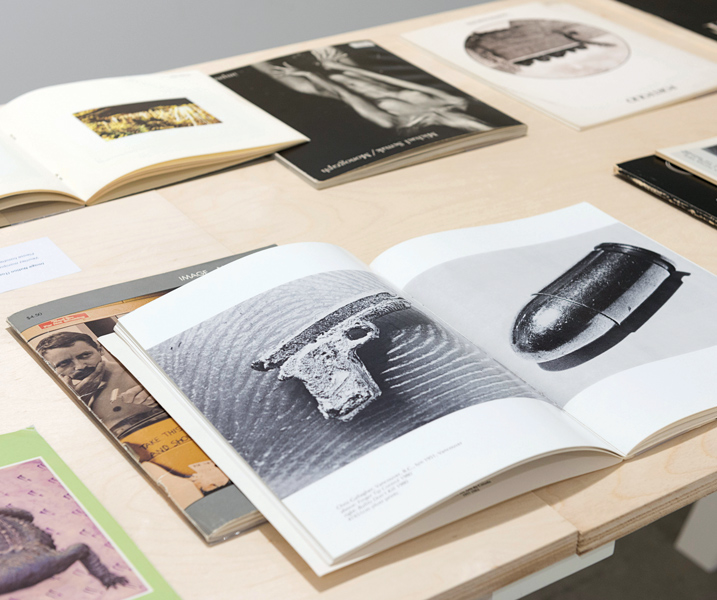

A number of magazines were created in the 1970s and 1980s as spaces devoted exclusively to the exploration of photography as a creative form. Seen through contemporary eyes, they can be understood as a key ingredient in the construction of a field of photographic art.3 These print objects contributed to the dissemination and actualization of photographic expression and discourse, and, as such, are today vital in retracing the unique development of contemporary photography in Canada.

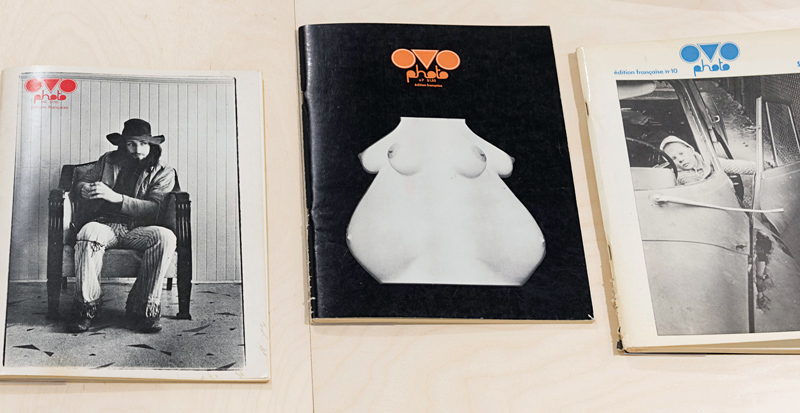

An overview of the photography magazines published between 1970 and 1990 reveals that there were two distinct yet complementary types: the almost-entirely image-based and the primarily text-based. The first category includes Image Nation (Toronto, 1970–82), Impressions (Toronto, 1970–83), and many issues of OVO (Montreal, 1970–87).4 The lack of text in these magazines (there was often nothing but a short introduction by the editors or, in OVO’s case, occasional interjectory articles and poems) reflects a “distrust” of the word that was current at the time, or certainly the idea that the photographic image, understood as a universal visual language, could and should be allowed to speak for itself.5 The primary aim of these magazines, it must be assumed, was the sharing of creative or non-commercial photographs among a specialized readership.

The first type is interestingly hybrid, for it borrowed many characteristics of the photographic book and, in my view, of an older style of pictorial magazine that was highly popular between 1930 and 1960. Issues of Image Nation and Impressions, especially, frequently played dual roles of magazine and book – or even catalogue. One example is number 6/7 of Impressions (1973), which reproduced the photobook version of John Max’s Open Passport series and acted as a record of the exhibition organized by the NFB/SPD in 1972.6 Another is Kenneth Fletcher and Paul Wong’s project Murder Research, which had been originally presented in 1977 as an exhibition and performance at the Vancouver artist-run centre Western Front and was published as a book work for number 21 of Image Nation (Winter 1980).7 In the absence in this country of an established photobook or art book publishing industry, these magazines sometimes provided the only permanent trace of important artistic projects.

Such autonomous, single-author works stand alongside the far more common strategy employed by image-based magazines: seamlessly combining a large number of individual photographs under a specific theme. The strong editorial voice apparent in these thematic issues connects them to the pictorial magazines of the earlier twentieth century (such as the American magazine Life, the French Vu, or Quebec’s La Revue populaire), which were put together by the expert hand of a picture editor. Even when several images by one photographer were incorporated within a theme (like a photo-essay would be in a pictorial magazine), their particular combination was determined not by the photographer but by the editor.8 Image Nation and OVO were big proponents of the thematic approach, combining a variety of images under such topics as “Photographs by Women About Women,” “Montreal Photographers,” “Punk Rock in T.O.,” “Femmes photographes,” “L’Autoportrait,” and “Les vitrines.”9

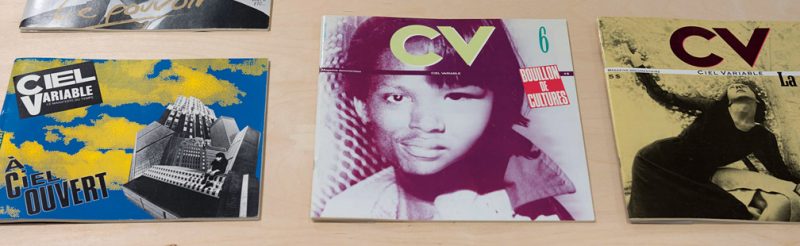

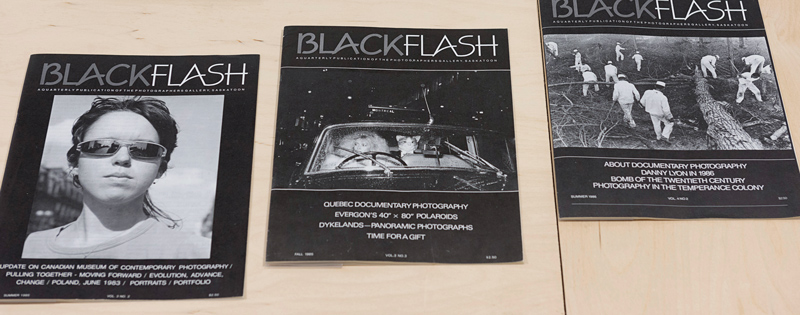

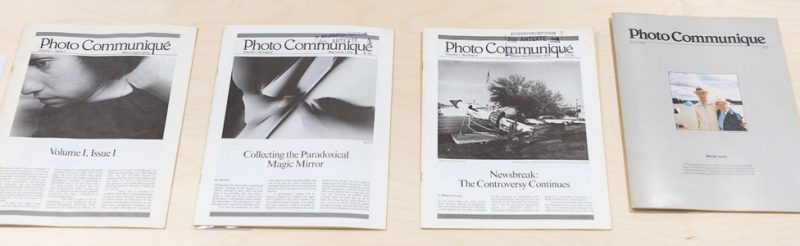

The second type of photography magazine helps to elucidate much of what is left unsaid by the first. The aim of magazines such as Photo Communiqué (Toronto, 1979–88), BlackFlash (Saskatoon, 1984–) and Ciel variable (Montreal, 1986–) was to provide a forum in which members of the expanding photographic community could engage in dialogue, and thereby develop a discourse of contemporary photographic practice in Canada. Still – despite evidence, especially discernible in the pages of Photo Communiqué, that the target audience was Canada-at-large – each of these magazines was grounded in a specific community and region.10

Obvious antecedents of this type of periodical can be found in community- or institutionally centred newsletters, with their gathering in one location of news and events of local interest. BlackFlash, for instance, which was at first published by The Photographers Gallery in Saskatoon, grew out of the cooperative’s previous internal publications, Exchange: The Photographers Almanac (1975–76) and The Photographers Gallery (1983). But this class of publication can also be affiliated with the burgeoning genre of the art magazine – a genre into which both BlackFlash and Ciel variable would transition during the 1990s. Like publications such as Parachute (Montreal, 1975–2006) and Vanguard (Vancouver, 1972–1989), this second type of photography magazine worked toward developing a field of contemporary art criticism in Canada, but with photography at its core.

A debate that was central to photographic discourse during the 1970s and 1980s, discernible in all of the magazines, concerned the distinction between photography-made-by-photographers and photography-made-by-artists. With the increasing use of the camera by conceptual artists, and the sanctioning of these artists’ work by regional and national art institutions, a divide was created between the photograph whose frame of reference was the history of art and the photograph that drew upon a specifically photographic heritage.11 At the crux of the debate was a desire to define photographic art – to take possession of it – at the very period when it was earning institutional and theoretical consecration. Exhibition reviews – and letters in response to reviews – became a prime site for engaging in this debate, frequently in strident tones. A good example is the review by Tom Gore, which appeared in the first issue of Photo Communiqué, of the infamous exhibition 13 Cameras, organized by the NFB/SPD and first shown at the Vancouver Art Gallery. The exhibition, which brought together works situated firmly on the photography-by-artists side of the dichotomy, along with Gore’s initial (scathing) assessment of it, acted as the driving force behind much public argument, carried out over several issues, on the state of contemporary photography, not only in Vancouver but in Canada as a whole.12

The eventual adoption by BlackFlash and Ciel variable of the art magazine model (as well as the demise of OVO in 1987)13 could be seen as reflecting the gradual “defeat,” from the 1990s onward, of the photography-by-photographers side of the debate. It is an indication, at any rate, that photographic art was being assimilated into the broader Canadian art world, making photography-centric institutions superfluous. It seems that once the need for photography institutions had been identified and acted upon, and once these institutions had become “public” by being officially recognized by provincial and federal funding bodies, the urgent question was: “What is Canadian photography and who has the right to speak in its name?” This question resounds through both types of photography magazine – the visual and the verbal – published during this period. The persistent questioning partly explains why the tone employed in these periodicals is so often fraught and why, in most cases, the strength to keep the magazines alive eventually faded.

The question continues to reverberate occasionally today (although in different, less regular circumstances), but it is largely evaded by the subsuming of photography into the post-medium-specific and post-nationalist art world. The very topic of Canadian photography – or Canadian photography magazines, for that matter – seems almost embarrassingly out of date, as though the words had been fished straight out of the 1970s. And it isn’t just “Canadian,” with all its identity-related pitfalls, that is problematic; even “photography” seems to jar. Whether or not contemporary Canadian photography exists today is a separate question. But that it once did cannot be denied.

2 See especially Martha Langford, “Introduction,” in Contemporary Canadian Photography from the Collection of the National Film Board (Edmonton: Hurtig Publishers, 1984), 7–16.

3 For an insightful application of the notion of “field of art” to photography, specifically in 1970s Montreal, see Lise Lamarche, “La photographie par la bande. Notes de recherche à partir des expositions collectives de photographie à Montreal (et un peu ailleurs) entre 1970 et 1980,” in Exposer l’art contemporain du Québec. Discours d’intention et d’accompagnement, ed. Francine Couture (Montreal: Centre de diffusion 3D, 2003), 221–265.

4 The first issue of Impressions was printed in Toronto in March 1970. The original editors were John Prendergrast and John F. Philips, co-founder of the Baldwin Street Gallery of Photography, Toronto. Subsequent co-editors would include Shin Sugino and Isaac Applebaum. The magazine aimed to showcase photographers whose work was “too personal to find an automatic commercial market.” In October 1970, the first issue of Image Nation appeared in Toronto. Edited variously by David Hlynsky, Fletcher Starbuck, and others, it succeeded the Rochdale College Image Nation, published from 1969 to 1970 by a printing collective based at the short-lived “alternative” Rochdale College in Toronto. Image Nation was aimed primarily at photographic artists active within the parallel gallery network across Canada. In late 1970, the first issue of OVO was published in Montreal. Initially a multidisciplinary leftist periodical based at the Cégep du Vieux-Montréal, it soon evolved into a photography magazine with an emphasis on the practice of documentary photography. From 1974 on OVO was edited by Jorge Guerra, joined later by Denyse Gérin-Lajoie.

5 Langford, “Introduction,” 14– 15; Lamarche, “Photographie par la bande,” 249–50.

6 Highly influential for its distinctive use of photographic sequencing, this publication is now commonly considered a masterpiece in the history of the photobook in Canada.

7 See “Murder Research, “Paul Wong Projects,” accessed August 25, 2016, http://paulwongprojects. com/portfolio/murderresearch/#.V6TBc1fQdZ0

8 A more direct antecedent may also be located in the books produced by the NFB/SPD in the late 1960s, and especially those published within the Image series, which also share attributes with the editor-driven pictorial magazines of the earlier twentieth century. Even the Image books that were devoted to the work of a single photographer (for example, Image #1, on Lutz Dille) were clearly and unabashedly composed by the editor, Lorraine Monk.

9 “Photographs by Women About Women,” Image Nation, no. 11 (1970); “Montreal Photographers,” Image Nation, no. 14 (1973); “Punk Rock in T.O.,” Image Nation, no. 18 (Fall 1977); “Femmes photographes,” OVO (September–October 1974); “L’Autoportrait,” OVO (January–February 1975); “Les vitrines,” OVO 10, no. 37 (1980).

10 The first issue of Photo Communiqué appeared in Toronto in March 1979. Edited by Gail Fisher-Taylor, the magazine was apparently created as a direct result of the Eyes of Time conference, held in Ottawa in 1978, at which the need was expressed for a publication that could unite the fine arts photography community. The magazine was dedicated to the exchange of information and ideas on photography in Canada. The first issue of BlackFlash appeared in 1984. Initially published by The Photographers Gallery in Saskatoon, it succeeds the institution’s newsletter The Photographer’s Gallery (1983). It aims to be a serious photography magazine with a strong regional base that also has an impact on photography nationally and internationally. Ciel variable was launched in Montreal in 1986 by the collective Vox Populi. This “magazine documentaire” was committed at the outset to reflecting, through photographs and texts, on contemporary social and cultural conditions. It became independent from Vox Populi in 1987. Over the course of the next few years Ciel variable was transformed into a thematically oriented photography magazine.

11 Lamarche, “Photographie par la bande,” 225.

12 Tom Gore, “Thirteen Ways to Wrap a Board,” Photo Communiqué 1, no. 1 (March–April 1979), 19.

13 See Jocelyne Lepage, “OVO, un anniversaire qui ressemble à des funérailles,” La Presse, June 21, 1986.

Zoë Tousignant is a historian of photography and a curator specializing in Canadian photography. She holds a PhD in art history from Concordia University. In her doctoral thesis, she investigates the dissemination of photographic modernism in popular illustrated magazines published in Canada between 1925 and 1945. She currently works as an assistant curator at the McCord Museum’s Notman Photographic Archives and as a curator at Artexte.