[Winter 2017]

By James D. Campbell

Jessica Eaton, a fast-rising star in the photographic world, has for some time now explored the notion of “colour is a verb” with rare verve, intensity, and thematic abandon. In her recent dovetailing series of works shown at Galerie Antoine Ertaskiran in Montreal as part of an exhibition aptly titled Transmutations,1 Eaton, already celebrated as a doyenne of colour theory, shows that she is preternaturally alert to the morphologies of colour as they occur across the breadth of the visible, and that she easily has a handle on their vast bandwidth. She seizes upon the moment of maximum visual gain with exquisite gravitas, and the sheer vivacity of chroma in her work has few equals or antecedents. The level of formal invention is high, and the results intoxicating.

A resolute seeker, her large-format film camera firmly in hand, she has developed a truly unique and compelling practice in pursuit of previously undisclosed secrets of colour. Without any handy bag of digital tricks, this supremely resourceful artist interrogates the medium of photography itself, deconstructing its essentials and underpinnings and bringing back from the margins where they had lain fallow what had once been its comfortably ostracized possibilities.

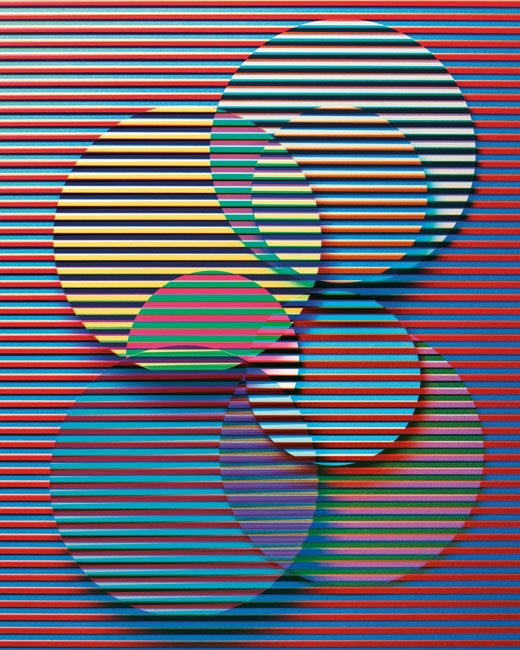

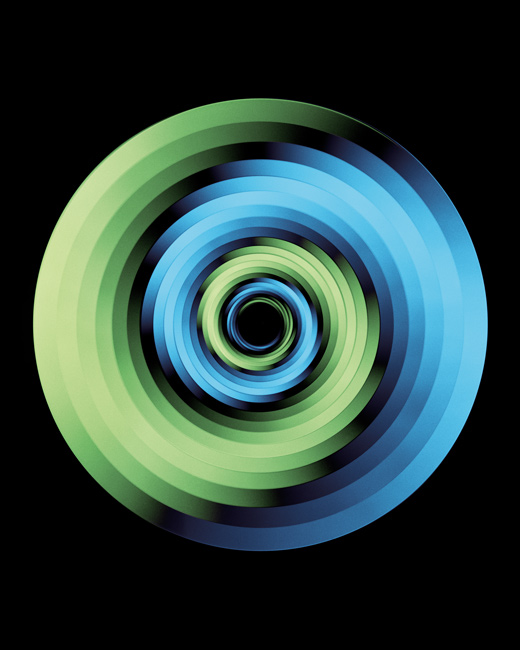

In her recent exhibition at Galerie Antoine Ertaskiran, Eaton selected captivating extracts from three new bodies of work, each with its own redoubtably heuristic core. She proceeds according to a trial-and-error methodology, deeply experiential and intuitive in its mien. The first series, Pictures for Women, is a hypnotic and moving homage to female artists through the use of kinetic sets and her signature experimental camera techniques. The pictures from the Revolutions series are also kinetically staged and set against black backgrounds, with colours that emerge from monochromatic grey-scale patterns finessed by the artist through her trademark colour-separation techniques. In the Transition series, following hard upon her acclaimed series Cubes for Albers and LeWitt (cfaal), she again employs additive colour techniques and staggered multiple exposures to produce ever more intricate, radiantly saturated geometries.

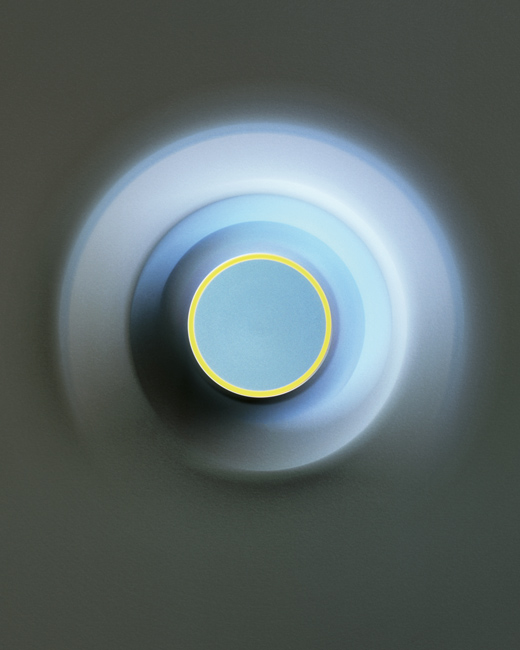

The standout here is the selection from the remarkable Pictures for Women series. Here, Eaton culls the punctum from a work by an artist that speaks to her and, through the most exacting technical manoeuvres, distils something like its chromatic essence. Her alambiccus is the camera itself, cozened through sundry hoops and rabbit holes, producing images that cross over from photography to painting and back again. Consider Georgia 01 (Georgia O’Keefe, Pelvis Series – Red with Yellow, 1945) (2016), in which the centre-most disc of yellow resembles bee pollen, pungent, seemingly friable, pigment-like, and seems to lift off the plane with beguiling and balletic excrescent grace – and this despite the fact that the plane is flat. Or is it? That Eaton makes us question both surface and support in terms of just what it is that we are seeing is part of her works’ allure and a reason that they stake such a lasting claim upon us. These are images that would make an ophthalmologist pause, a plasticien painter salivate, and a more conventional photographer gasp. She explores the limiting definitions, fey minutiae, and latent depths of seeing, inside out and upside down.

Drawing upon the work of art stars such as Helen Frankenthaler, Sonia Delaunay, Tomma Abts, and Hilma af Klint, Eaton essays a dazzling act of tribute that is also a celebration of abstraction itself. Take Hilma af Klint’s Svanen (The Swan, 1917, an abstraction never exhibited during her lifetime), which is remarkably kindred in spirit to the works exhibited here, but several light years removed in kind from the painting homeworld. Still, speaking now as a critic of advanced painting for almost forty years, I am reminded just how much more there is still to say about painting from within the world of analogue photography – if, that is, you possess the enviable technical chops and wildly unhinged imagination of a Jessica Eaton.

The Revolutions and Transition works (all archival pigment prints, 2016, with the exception of Revolutions 20, a silver gelatin print2) remind us of Marcel Duchamp’s Rotoreliefs (1935), a set of six double-sided discs designed to be spun on a turntable at 40–60 rpm. (Duchamp and Man Ray filmed early versions of the spinning discs for the short film Anémic Cinéma.) That work, which grew organically out of Duchamp’s abiding interest in optical illusions and mechanical art, is a haunting forebear to Eaton’s equally enticing photographs.

Like those two-dimensional rotoreliefs creating an illusion of depth when spun at the correct speed, Eaton’s otherwise static images draw the viewer down the rabbit hole into a dimension of stranger things. But rather than engage or replay the often dizzying order of Op Art, there is no enervating spectre of déjà vu here. Eaton’s work neither estranges nor deranges the viewer, who is left with a palpably sensuous aftertaste of colour’s heady elixir. Indeed, her works remind us not just of Duchamp’s unorthodox experiments but also of nineteenth-century microscope slides, which opened up new, unforeseen microworlds of nature in the same way that Eaton now travels a compelling geography of the visible at once voluptuous and unforeseen. She maps the terra incognita of the universe of pure chroma. One might suggest (as the cartographers of an earlier era did in their maps to annotate the unknown): “Here be dragons.”

Eaton attempts to deconstruct chroma itself, unearthing its true underpinnings, but ends up celebrating it in all its incarnations. A wily conjuror and illusionist at heart, her discipline is almost purely scientific in its approach, but her goal, it seems, is religion. Rare is the photographer who is as much an unabashed hedonist as a nose-to-the-bench research scientist. This exhibition reminds us why she is seen as the doyenne of colour theory, and a dealer in first-level perceptual ecstasy. Like Lorna Bauer, a fellow traveller with analogue camera ready in hand, Eaton demonstrates both jaw-dropping technical expertise and an undying desire to show that what appears within the ambit of the camera lens is not the world we know but a host of possible worlds heretofore undreamt of.

2 It is an archival pigment print rather than a gelatin silver print that was exhibited here, but I defy most viewers to tell the difference.

James D. Campbell is a writer and curator who writes frequently on photography and painting from his base in Montreal.