[Spring-Summer 2017]

By Francine Paul

Waters lands suns clouds

And then all this fundamental freezing

Ice and icebergs

Floes and turrets

Chorbacks and ropaks

That the ancient Empedocles

never spoke of

Foulanges and snows

Over there all over there1

— Jean Désy, Petite suite de poèmes nordiques

Whereas Jean Désy’s poem echoes Nordic beauty by choosing the inventive vocabulary of the North and its ice forged by geographer Louis-Edmond Hamelin,2 Alain Lefort’s recent landscapes create sensitive and personal representations of it. With the photographs in his recent series Eidôlon and Sans titre (Eidôlon), Lefort attentively observes the multiple layers of the mystery of “over there all over there.”

Photographic Projects. Since 2010, Lefort’s photographic series have evidenced his desire to go to increasingly remote regions alone to photograph natural phenomena; most recently, he has been intrigued by icebergs, huge in both dimensions and appeal. Like many of us, his imagination may be fed by accounts of the voyages of the great Arctic explorers Roald Amundsen, Robert Peary, Frederick Cook, and Sir John Franklin. Literature, including the writings of Walt Whitman and Herman Melville, is another source of inspiration for Lefort, as Sylvain Campeau and James D. Campbell point out in their monograph devoted to him.3

No doubt Lefort also keeps in mind the private and public photography campaigns of the nineteenth century and, closer to the present, the DATAR photographic missions in the 1980s that offered, in the context of contemporary reflections on the concept of landscape, a personal vision demonstrating that a “representation of the landscape must be created rather than simply recorded.”4 As the designer and initiator of his photographic projects, Lefort is their principal sponsor, occasionally supported by research grants.

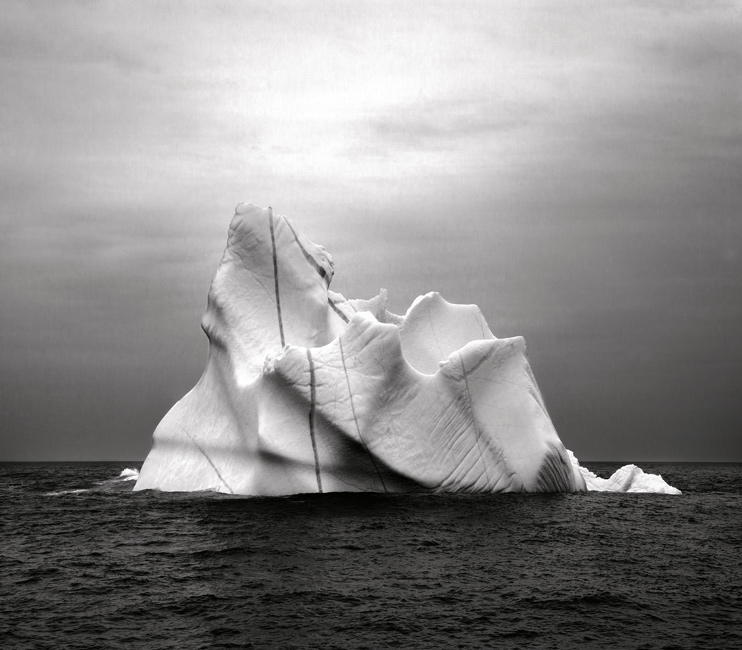

Nordic Landscapes. In spring 2015, Lefort went to Newfoundland, equipped with his analog and digital cameras, to find and track drifting icebergs. Choosing black and white, rather than colour, as an aesthetic parameter and almost square framing rather than panoramic horizontality, he clearly establishes that the picturesque, the anecdotal, and neopictorialism are not part of his photographic venture. Faced with the wild expanse of the visible world that spread before him as far as the eye could see, he opts for an objective attitude emphasizing depth of field to better discern the shapes, surfaces, lines, shadows, textures, and tones of the icebergs. Lefort’s landscapes transport us to the heart of an open and immense nordicity, offering an almost exponential tonal chart of whites, greys, and blacks of icebergs standing out against the horizon or packed together, depending on whether he has captured them from far or from close. Thus, by standing still, blocking his gaze, and framing a site with his camera, he has selected “the ideal tool to materialize”5 the concept of landscape, defined by Henri Cueco as “an intellectual point of view, an abstraction, a fiction.”6 This construction, also forged by models of painting, is a representation: “Landscape would thus be the world as it is seen through a window, whether this window is simply part of a painting or is confused with the painting itself in its totality. The landscape would be a framed view, and in any case an artistic invention.”7

Two Photographic Scenarios. Lefort invests the scholarly and technical performance of the photographic landscape by fostering two scenarios inspired by the wandering of the floating boulders of ice that drift down from the High Arctic to between the coasts of Labrador and Newfoundland. In both scenarios, the photographer frontally collides with the tranquil exuberance of the glacial figures,8 on the look-out for their presence, for the ideal angle, for the meaningful instant to point the camera at them like a hunter would, for, as Susan Sontag has put it, “There is something predatory in the act of taking a picture.”9

In the landscapes in the Eidôlon series, what is immediately striking is a succession of horizontal planes superimposed on each other from the lower edge of the image to an almost infinite distance on the horizon line that divides the image into dark and light zones, in front of which, in the centre, one or a few luminous icebergs seem to be deposited. The frontality of the instant idealizes the majestic effect of the almost portrait-like isolation of an enormous form or figure placed against a background of sea. Curves, hollows, differences in levels, diagonals, verticals, plays on shadow and light magnify and individualize the architecture of the floating icebergs as if they were animals on parade.

In the other series, Sans titre (Eidôlon), the horizon line has disappeared in favour of close-ups that melt into each other, producing, in their frontal proximity, pieces of atmospheric, abstract winter landscapes. The contrast, muted to several tones of whites and greys, accentuates the granular, opaque textures of the icebergs. The tight framings on the folds and refolds of the surface crystals emphasizes the generous materiality of the ice submitted to the random force of the wind, currents, precipitation, and sun, which constantly sculpt its contours by shaping bumps and polishing surfaces.

Lefort’s dramatic landscapes, both long-distance shots and close-ups, call our knowledge of icebergs into play. It is common knowledge that they are composed of freshwater and that their visible portion above the waterline represents only 10 percent of their mass, with nine-tenths left underwater. The laws of physics also remind us that icebergs only look stable – a false stability that is revealed when the part immersed in the dark ocean flips over, making the ice crash and groan and creating whirlpools and waves. Icebergs’ fatal beauty has a monstrous hidden face that is transformed into a threat to anyone nearby if the monster crouched beneath, in the dark sea, suddenly springs into action.

Landscapes and Imagination. Thus, Lefort’s photographs open the sluices of the imagination and demonstrate that “the very art of landscape is a component of the most elementary aesthetic perception, providing human receptive capacity with the tension and creative force dear to the imagination.”10 They take us to the fertile territories of allegory foretold by the title Eidôlon, borrowed from ancient Greek literature, which refers, as James D. Campbell observes, to “a shade or phantom lookalike of the human form.”11 It may also refer to the biblical figure of the Leviathan, a monster that lies dozing deep in the ocean and must not be awoken.12

The form-figure and visual appeal of the iceberg, as revealed by Lefort, and transports of the imagination combine to induce viewers to attribute a negative value to the sublime here. As Edmund Burke has written, “Whatever is fitted in any sort to excite the ideas of pain and danger, that is to say, whatever is any sort terrible, or is conversant about terrible objects, or operates in a manner analogous to terror, is a source of the sublime.”13

And here we are adrift of meaning, taking allegorical support from the process of deconstruction and fragmentation of icebergs that ends with their total dissolution. Following a long journey, they return to their primary liquid state, original water, leaving no trace. It is a journey similar to ours, as we return to the land, or perhaps it is a question of global warming, of which the disappearance of the great glaciers is symptomatic. Carried away by the flow of time, the instants that produce Lefort’s photographic tableaus have the power “of freezing time.”14 Again here, Sontag’s pertinent words take us as far as do Lefort’s landscapes in the semantic movements of cold and solitude.

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 Daniel Chartier and Jean Désy, La nordicité du Québec – Entretiens avec Louis-Edmond Hamelin (Quebec City: Presses de l’Université du Québec, 2014).

3 Sylvain Campeau and James D. Campbell, Alain Lefort (Longueuil: Éditions Plein sud, 2016).

4 Jacques Sallois, quoted in the preface to Paysages, photographies. La Mission photographique de la Datar, Travaux en cours 1984-1985 (Paris: Hazan, 1985), 11 (our translation). Quotation taken from André Rouillé, La photographie (Paris, Gallimard, “Folio essais,” 2009), 495.

5 Henri Cueco, “Approches du concept de paysage” (1982), reprinted in Jardins et paysages. Textes critiques de l’Antiquité à nos jours (Paris: Larousse, 1996), 518 (our translation).

6 Ibid., 517 (our translation).

7 Jean-Marc Besse, Le Goût du monde. Exercices de paysage (Arles: Actes Sud/ENSP, 2009), 19 (our translation).

8 The French original, “figures glacielles,” was a neologism forged by Hamelin in 1959 to express the phenomenon of floating ice; see Chartier and Désy, La Nordicité du Québec, 97–98.

9 Susan Sontag, On Photography (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1977), 14.

10 Raffaele Milani, Esthétiques du paysage. Art et contemplation (Arles: Actes Sud, 2005), 66 (our translation).

11 James D. Campbell, “Sea Phantoms: The Numinous Photographs of Alain Lefort,” in Campeau and Campbell, Alain Lefort, 53n2.

12 Jean Chevalier and Alain Gheerbrant, Dictionnaire des symboles (Paris: Robert Laffont/ Jupiter, 1969), 567.

13 Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (London, 1824), 34, emphasis in original.

14 Sontag, On Photography, 111.

Francine Paul has degrees in political science and art history. Since completing her doctorate, her main research has concerned encounters among the visual arts, landscape, and nature in contemporary creation.

Alain Lefort lives and works in Montreal; he earned a degree in photography from Concordia University in 1995. Since the early 1990s, his work has been in more than fifty solo and group exhibitions in Quebec and abroad (including Albania, the United States, and Portugal). His works have been purchased by Cirque du Soleil, the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, Loto-Québec, and UMA (la Maison de l’image et de la photographie) and have been the subject of numerous published texts.

alainlefort.com

Purchase this article