[Spring-Summer 2017]

Les révolutions sidérales

Plein Sud

October 1–November 5, 2016

By James D. Campbell

In the photoworks in this exhibition, Fiona Annis dilated with poetic acuity on the clockwork of the heavens. She mined resources as varied and recondite as the first spectroscopic data on the trajectory of Halley’s Comet, recorded in 1910, and Binary Stars: A Pictorial Atlas, 1992. Annis is as much an aficionado of Marcel Proust as she is of Sir John Herschel,1 and she is a tireless researcher (and practitioner) not only of photographic techniques from an earlier era – such as wet-collodion – but contemporary philosophical and scientific thought.

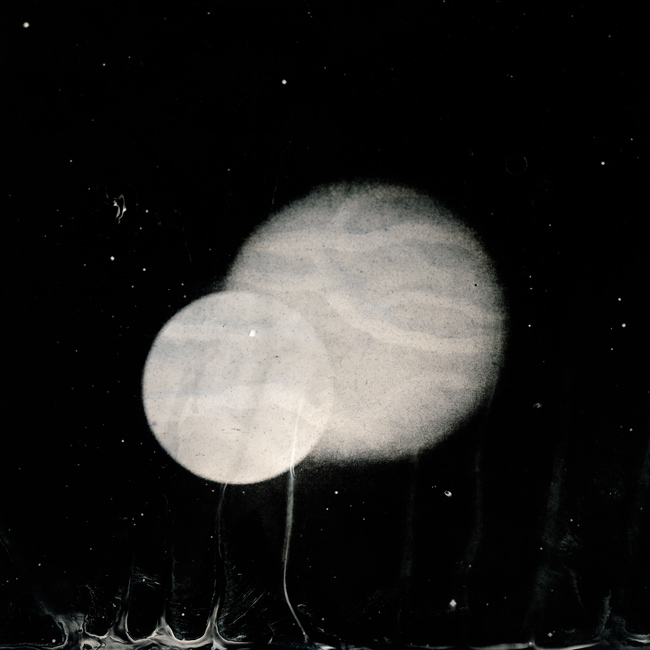

The phenomenon that animated Annis’s exceptional work in this exhibition is a binary star system, consisting of two stars orbiting around the same point. In fact, it is a powerful metaphor for her project as a whole, and the latest images from the Hubble telescope help to explain our own fascination with work that uses antiquated photographic means to shed light on the latest discoveries in astronomy. “Binary star” is often used synonymously with “double star,” but the latter also notably means optical double star. These optical doubles, luminous Doppelgängers, are the astral ghosts that haunt her work like unseen companions, exerting a force of gravity both on her undertaking and upon our attention.

Indeed, the works in the exhibition were resilient magnets for the eye; they weighed on our perception in a peculiarly elliptical manner, inciting the imagination to take fanciful flight. They possessed aura. If Annis’s ongoing fascination with the relationship between photography and astronomy feeds her aesthetic, their intersection here enlivened our own. Her studies in the early history of photography led her to understand how photography is indebted to the development of the optical lenses first developed and used by astronomers. Those lenses offer a compelling binary analogy for vision and visuality.

Light and times are the central axes around which Annis’s aesthetic restlessly coils. She uses the darkened gallery space as surrogate for a morphing galactic plenum rather than a mute void. In Double Moon Crossing (2016, C-print enlargement of wet-plate collodion, 81 × 61 cm.), Double star (saule) (2016, C-print, 58 × 50 cm.), and Double Star (Albireo) (2016, C-print, 41 × 31 cm.), the tremulous and spectral celestial bodies suggested an immensity and age almost unfathomable in their mien.

The quotations displayed on accompanying aluminum wall panels were uniformly pungent and drawn from a collection of authors including Walter Benjamin, Camille Flammarion, James George Frazer, Victor Hugo, and Rebecca Solnit. They may have offered the eye a rest between photoworks, but they also offered a real trigger for the imagination, given their suggestive potential in drawing a radius between text and image and the artist’s intentions.

If Annis meditates meaningfully on temporality and light at every turn, it is perhaps because she has the soul of a poet. Her eloquent ruminations instigate our own. We were reminded, as we made our transit of this exhibition, of what Luce Irigaray, the Belgian-born French feminist, philosopher, linguist, and psycholinguist, wrote: “The perfect clarity of intelligible light is achieved as a progressive recovery from the displacement of light, which in the sensible realm is ambiguously differentiated from unrepresentable material obstacles, like the tain of a mirror, the bodies which cast shadows, the water’s reflective surface, the cloth divider or the walls of the cave.”2 The perfect clarity of intelligible light. It’s well said – and remarkably relevant to the images under discussion here.

Although the images in this exhibition were hauntingly resonant of a universe that may well be largely unfathomable to us, they are still not altogether beyond our ken (thanks to the Hubble). And the light of dying stars stakes an unavoidable claim. Such was the case with Halley’s Passing (2014), a light box activated by electromagnetic induction and showing a reproduction of a photographic plate produced in an observatory that tracked the passage of Halley’s Comet in 1910. Viewers could illuminate the light box at will by cranking an ergonomic handle, shedding a welcome, if spectral, light on the celestial image. Annis is no mortician of dying stars but their unabashed celebrant, and, in distilling the light of other days, she reminds us of our own mortality. As though through a pane of slow glass, an oculus, she searches for and finds a light worthy of illuminating our own small patch of words, our own acreage of darkness.

2 Cathryn Vasseleu, Textures of Light: Vision and Touch in Irigaray, Levinas and Merleau-Ponty (New York: Routledge, 1998), 8.

James D. Campbell is a writer and curator who writes frequently on photography and painting from his base in Montreal.