[Fall 2017]

By Alexis Desgagnés

André Barrette likely never wanted his art in the spotlight. That is why, outside of the community of artist-run centres in Quebec City, relatively little is known about his discreet but important contribution to Quebec photography landscape in recent decades. Yet, from his obvious affection for cultural manifestations that we naturally associate with a working-class register – hunting, sports, and fast food, for example – Barrette has built a coherent body of work, with a radical yet sensitive aesthetic, most recently displayed in Fin de Siglo,1 a self-published book quietly launched in January somewhere on Quebec City’s Côte d’Abraham. Without reviewing Barrette’s entire career from Matane, where he studied, to this book, I would like to say a few words about some of his preceding series, and then talk about his view of Cuba.

In the corpus Les rituels, parcours de chasse (1999), Barrette’s interest in “popular” culture was already evident; it is a culture innate to the actions, gestures, tastes, and practices of the masses, including in the visual space – as opposed to preconceptions, works, habits, and institutions of the elites – although, in the era of industrialization of culture, this distinction would have to be nuanced.2 More evocative than documentary in tone, Barrette’s photographs portray hunting as a ritual of communion with nature: poetic, silent tracking, the suspense between the call to and the wait for the animal that is invisible, both in the woods and in the images. Not the luminous, drunken beast of the movie. Instead, the quest is blurred, off-screen: before the lens, as before the arrow that one draws back, as one awaits the prey, the landscape is everywhere. Then, finally, the beast appears – as Sylvain Campeau has noted,3 Barrette sees a correspondence between this immemorial food-producing activity and the practice of photography: in La présence, the final image in this series, the artist’s shadow appears against a tangle of weeds.

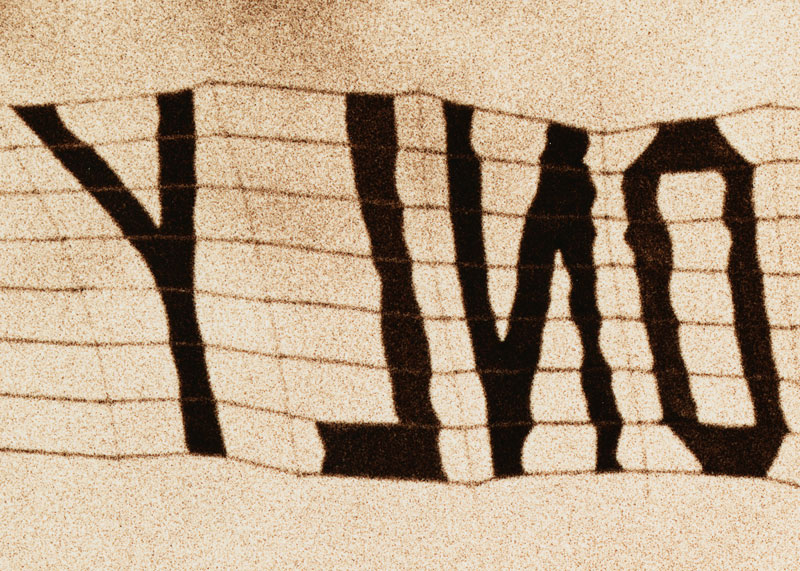

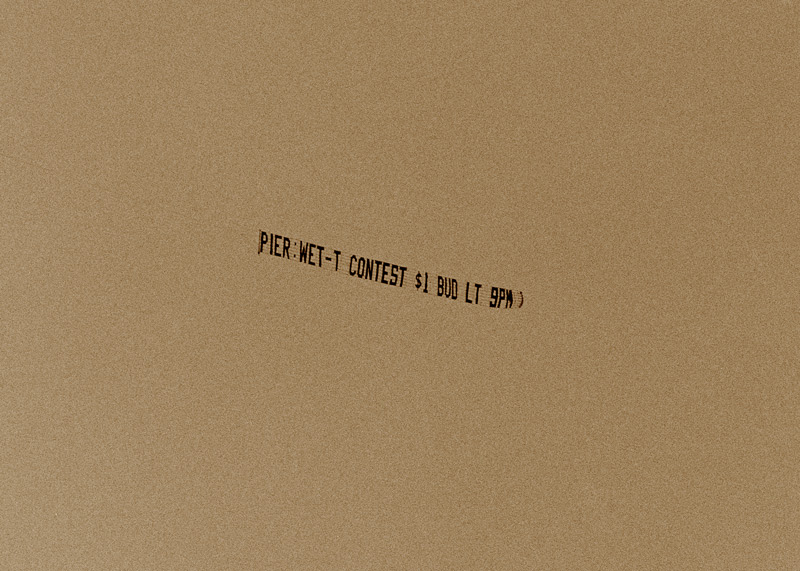

Barrette’s work has been through many incarnations over the years. In ALL U CAN EAT (2002–13), he draws on the popular imagination more explicitly by diverting into his photographs the words on aerial advertising banners pulled by airplanes above beaches on the American east coast. As an artist rather than a tourist, Barrette photographed the banners during his summer travels through the United States. The laconic messages – all in capital letters, with rudimentary syntax – invite vacationers to take part in wet-tee-shirt contests or to buy all the beer or pizza slices they can consume. He transposes these texts, whole or fragmented, into exaggerated granulation, sublimating the linguistic hooks into elementary visual signs. Airplanes and words thus enlarged are arranged in dynamic ensembles that reconfigure cheap entertainment offers with a cunning and irony reminiscent of Dadaist collages or Friedlander’s Letters from the People (1993). Here, Barrette brings to light the populism underpinning lifestyles and consumption habits promoted within the mass tourism economy. In assembling these fragments of desire-merchandise, he forcefully summarizes the prefabricated essence of a “NEW FREE SAFE LITTLE LIFE” made of junk, the promise of incredibly cheap capitalism.

Barrette’s interest in visual manifestations and socioeconomic intricacies of popular culture is notable in his book Marx, la danseuse et la coupe Stanley,4 published in 2010. The result of a correspondence with Rémi Ferland, who wrote texts in dialogue with photographs taken by Barrette at the threshold of his art career, this excellent little book looks back, not without nostalgia, at Quebec from 1975 to 1980. Barrette and Ferland set out to show the now-mythical character of this decisive era of Quebec culture, if there is one, at a time when rectitude seems to have won out over the essence of yesterday’s aspirations (although, for some, those aspirations still live today). From the beer-filled taverns to the frenetic glory of the Expos and the Canadiens – featuring a victorious Yvan Cournoyer and his cup – the marquees of porn movie houses, the BBQ restaurant signs, the nude dance clubs, and the fight for socialism, the authors roll out iconic references to popular Quebec in the later part of this legendary decade, which closed sadly, as does the series, with the defeat of 1980.

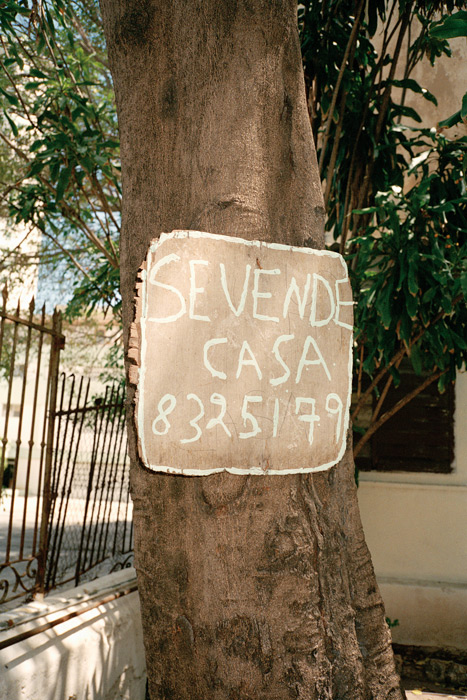

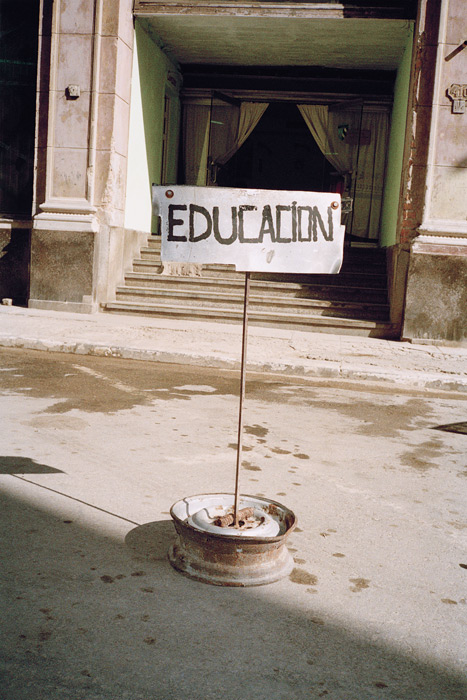

Fin de Siglo. It is with this nod to the typography of another age, the Batista era, and the renowned Havana department store of the time that Barrette’s new book opens, along with a list of almost thirty places visited to produce this corpus of images, a powerful visual testimony to Cuban society as the Castro regime winds down. Photographed from 2008 to 2016, during a number of stays on the Caribbean island, Fin de Siglo is divided into three parts that invite the reader to wander through the mazes of Cuban visual culture. Barrette focuses on a variety of objects and images, brightly coloured and often misshapen, sometimes frankly lopsided, that enliven Cubans’ living environment. It is an environment that is precarious, obsolete, worn, but it nevertheless expresses the creativity and vitality imposed by the material conditions of existence on the communist island.

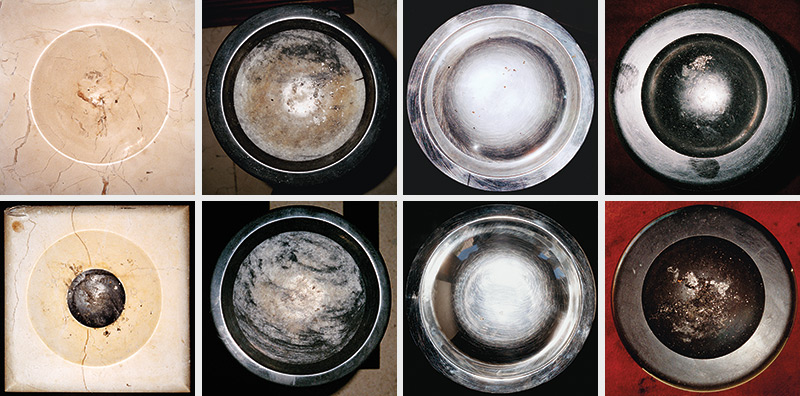

Faithful to the sensibilities of Marx, la danseuse et la coupe Stanley, in continuity with the aesthetic franchise of ALL U CAN EAT, Barrette frequently makes use of a raw direct flash to show Cuba without compromise. Skilfully avoiding the trap of exoticism, he always looks askance at the stereotypes of Cuban culture and never lets his gaze be diverted by the mythology peddled by the tourism industry and the regime. On the streets of Havana or Varadero, Barrette accepts as true guides only his photographic vision and the instinct of his hunting eye. The evidence is in the second part of the book, composed of twenty straight-on, vaguely abstract images, in a square format, of circular-shaped ashtrays photographed from a high angle, perpendicular to the ground; the only clue to what they are is the presence of Cuban cigar ashes.

Echoing the first part of the book, Barrette concludes with a more direct evocation of Castrist ideology. But despite the efforts deployed to stage the regime, with its propaganda, its museology, its cinema, its history, its spangled caps, and its revolutionary moustaches, Barrette is not fooled about its likely expiration date. And today, on televisions in Cuba, the shadow of the American beast is rising.

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 “The oligarch thus does not disappear into the general public, even if he shares the same crap, from the cultural point of view. Although he makes a poor reproduction of the courtyard to which he aspires, the financier, press magnate, and administrator of the Total oil company, is satisfied with this simulacrum that absorbs him – him and his. And it is as full as it is big – that is, for him, mass-marketable. This is the stamp of his power: showing himself capable of dragging a whole community into the effects of his bad taste and placing them, without no possible resistance, under the name ‘culture.’” Alain Deneault, La médiocratie (Montreal: Lux Éditeur, 2015), 161 (our translation).

3 Sylvain Campeau, “L’objet de la traque,” Vie des Arts, no. 175 (2000): 66.

4 André Barrette, Marx, la danseuse et la coupe Stanley (Quebec City: Les éditions J’ai VU, 2010).

André Barrette’s photographic production is rooted in the reality of popular culture, which becomes his creative space. His photographs offer a rereading of his initial subject, unfurling in narrative series that border on fiction. His work has been shown in galleries, in situ, and in publications. He has had exhibitions in Canada, France, Poland, and Cuba. He lives and works in Quebec City.

Alexis Desgagnés is a Quebec art historian, artist, and author. His book Banqueroute, a collection of poems and photographs, has recently been published by Éditions du renard.