By Jill Glessing

Promotion for “Canada 150” – marking the inception of the colonial enterprise of the “Dominion of Canada” and its unequal union with Quebec – was tepid, perhaps foretelling the inevitable response: a hundred and fifty years old – really? The land, of course, had been inhabited a little longer than that – about twelve thousand years – by Indigenous peoples.

This foundational model – of palimpsest or wax tablet – the processes of overlay, reinscription, and erasure, and the resultant friction could be seen in relation to many of CONTACT 2017’s primary and featured exhibitions.1 Responding to that nationalist celebration, some exhibitions in the festival, which bore the title “Focus on Canada,” prompted gentle fondness for the country’s lands and communities – both settler and mixed. Other significant exhibitions attended to the darker underside – pointing to patriarchal and white power and the chafing friction related to racial and gender violence. Particularly prominent were Indigenous artists, whose activist works revisited their history as Kanata’s first peoples and the natural world they inhabited.

A gentler perspective on Canadian cultural identity was offered by Katherine Knight’s archaeological dig into the literal and rhetorical fabric of domestic Nova Scotia culture via a rural folk art: needlework mottos. These ornately colourful aphorisms in Gothic script were produced from the mass-produced punched-paper patterns popular around the turn of the twentieth century. Collaborating with Knight in Portraits and Collections, the Textile Museum of Canada displayed a large selection of framed fabrics with their embroidered wisdom, such as “What is a Home without a Father?” (or, variously, “a Cat”), drawn from a much larger collection of 173 pieces that once covered the pastel walls of a home overlooking Caribou Harbour. Knight added layers to these historical artefacts through her excavation project Caribou Mottoes (2006, ongoing), presented here in mixed-media format. Three small square photographs showed light-filled interiors, their walls covered with the framed needlework pieces; large photographic closeups of individual framed pieces were paired with images of their messy reverses, released from their frames, revealing stray threads and old newspaper backing. Two audio-video works further fleshed out the story: an evocative triptych meditation on the sea and the passing of old ways of life focused on bobbing buoys, their original warning bells destined for replacement by digital sound (Buoy, 2003); in another, the needlework pieces were coupled with voices of women and girls in the community reading their inscriptions.

Three video works by Johann Hallberg-Campbell capturing imagery from the other two Canadian seacoasts – Arctic and Pacific – were installed in a small alcove in his Harbourfront Gallery exhibition, Coastal (2010, ongoing). The relatively abstract imagery of Arctic, Tuktoyaktuk, Northwest Territories (2016) – aerial views of snow-covered expanses and closer captures of roiling seawater with accompanying sea and bird sounds – was more poetic than were the conventional colour photographs of coastal peoples and places that crowded the remaining walls in collage format.

Coastal imagery was similarly featured in Michael Snow’s New-foundlings at the Prefix Institute of Contemporary Art, but through dreamier camera explorations. Four videos explored human and camera perceptions of time and motion and the similarly flickering spaces of water, land, and vegetation that they recorded. These playful experiments were also highly evocative of place: in Solar Breath (Northern Caryatids) (2002), sea breeze and sound filled over an hour of looped audio-visual pleasure as light salmon-coloured window curtains lift, give a teasing glimpse of the outdoors, then are sucked back against the screen with an urgent “thwap.” Occasionally, a light domestic clatter of voices and dishes introduces the presence of the camera and its operator. On a small monitor, Sheeploop (2000) settles our mesmerized attention on a curved green pasture overlooking a lively white-capped ocean. In slow real time, grazing sheep move into, then out of, the frame, creating a “loop” and setting the pace of a rural seacoast.

Sharing affinities with Snow’s filmic experiments is British-based Canadian artist Mark Lewis. Three new video works drawn from his series Canada were projected onto walls at the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO). Like Snow, Lewis uses exploratory camera modes: the medium has its own agency – we get to know the camera, what it can do, how it sees, and we are invited to consider its cultural meaning. But, unlike Snow’s camera’s interactions with more intimate and rural spaces, Lewis’s roving, distanced, sometimes drone-operated camera often scans modern urban spaces with a voracious, omniscient eye. That signature panoramic style purveying the landscape with cool camera view was applied to one of the works here – Valley (2017). In this work, the land explored is the urban mess around a section of Toronto’s Don Valley. The camera visits, with a slow, critical gaze, the bit of nature that just manages to survive – grey tree skeletons, scrub vegetation, and detritus edging the Don River – the parkway with its whizzing cars, train tracks, warehouse buildings covered with advertising and brand names, an occasional jogger on a bike trail. Partway through the tour, the camera explores the abstract compositions created by electrical towers and lines against a blank sky, suggesting the rational carving up of modernist spaces. More pointedly, the camera grazes past, and settles briefly over, an Indigenous man outside his makeshift home under a bridge. He crawls into his tent, snow begins to obscure the scene, the camera moves on.

In Things Seen (2017), the camera displays more ominous and predatory tendencies. Entering an expansive, empty Lake Ontario beach on an overcast day, the camera quickly latches onto its target – a woman wearing a dark wet suit emerging from the water. At first she is oblivious to the menacing and voyeuristic eye trained upon her; then, she stares it down as it circles closer and closer to her. This modern woman – an update of Édouard Manet’s radically assertive Olympia (1863) – defends herself against the invasive gaze, sends it away, and returns to her solitary enjoyment within the natural lake-scape.

At Gallery TPW, Luis Jacob’s exhibition Habitat made more pointed reference to the colonizing, demarcating inscription of spaces and bodies through urban development and representational technologies. In Sightlines, Toronto’s steady transition toward its current condo-controlled landscape was mapped out through rows of colourful historical postcards that stretched in a line across the walls of one room. The modernist aesthetic, introduced to the city with Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Toronto-Dominion Centre towers in 1967, and expressing the values of international finance, increasingly erased, overlay, and reinscribed the city’s original colonial structures.

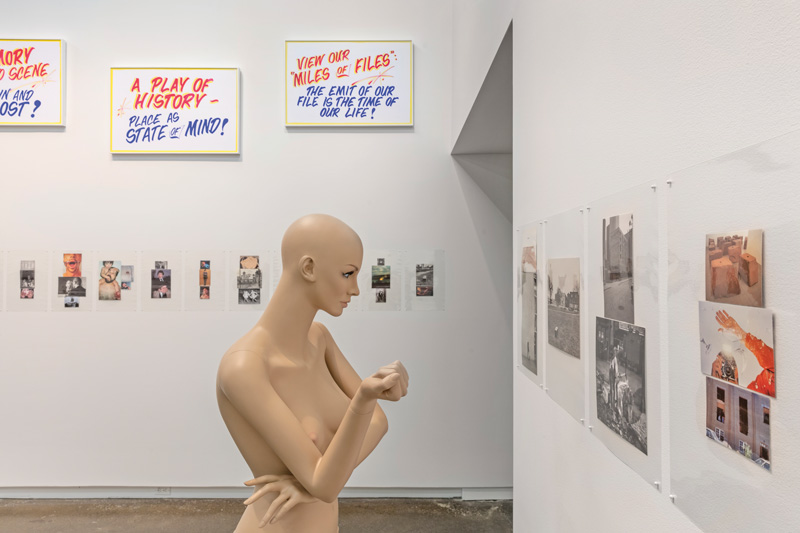

Leading into a second, larger room, and reiterating the theme, was a large map of the Ward – Toronto’s historic, central area that once housed poorer populations, razed to make room for the growing financial capital of Canada. Inside the room, two installations homed in on the real people and cultures hidden within those distanced postcard views. Album XIV, the latest in Jacob’s series, presented a long line of small, laminated, page-like collages of media images that obsessively asserted particular motifs, foregrounding processes of visual containment, demarcation, and control of spaces and identities: frames within frames; maps, models, and architectural and urban plans; boxes and lines; ways of producing and looking at images, especially camera images; and exhibitions with people circulating in and around them. The compulsion toward rational containment outlined in these first images is questioned through the concluding images, which, in their depiction of demolition and distortion of discrete spaces and buildings, suggest potential for liberation and renewal.

A row of small hand-painted signs, Public Domain, circled the upper walls, offering recognized and obscure references to Toronto’s buried art culture and continuing themes of destruction and overlay. The cursive and colourful signs duplicated the flamboyant style of those that plastered the now-empty popular emporium for all things cheap, Honest Ed’s Warehouse; the same painter, Wayne Reuben, was persuaded by Jacob to create this one last series. The historical landmark, important for its provision of affordable goods for generations of immigrant shoppers, will be replaced by condos – erasing significant markers of Toronto’s history. Parallel to this overwriting of cultural spaces is the ideological inscription of bodies and social identities. Images, integral to these processes, help to impose, but can also loosen, such psychical colonization. Artists’ interrogations and resistances around gender, sexual, and racial identities were featured prominently at the festival.

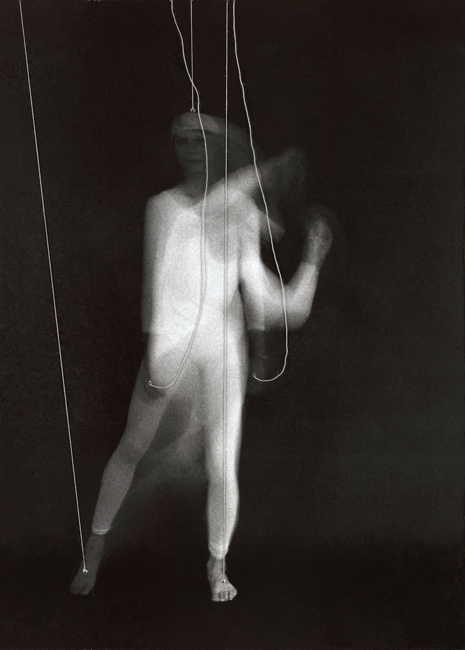

Suzy Lake’s exhibition at the Ryerson Image Centre (RIC) and the accompanying catalogue (published by Steidl) came with her 2016 Scotiabank Photography Award. Unlike the extensive area for Lake’s exhibition at the AGO last year, this smaller space offered a finer selection of works that seemed more in keeping with her intimate explorations of identity constructions and constraints. Important for curator Gaëlle Morel was the tracking of Lake’s artistic development and the linkage between concept and material; hence, the artist’s work prints, notes, and examples from different stages of her career were carefully laid out. In Lake’s work, the locus of identity and power relations is the body; she performs processes of becoming and resisting with her own body and primarily through the photographic medium, both of which are excavated and unravelled. Works ranged from earlier black-and-white images from her Choreographed Puppet series (1976/2007–15) in which her body is tied and trapped in binds, to later, more delicate works that further explored the photographic medium. For her series Fascia (1997–99), photographs of her own back were printed on copper-toned, lifted, and cut resin-coated paper, producing soft pink, skin-like layers shaped into a woman’s slip or stretched with pins inside a specimen vitrine.

Moroccan-born Montreal-based artist 2Fik also struggles within a prescribed status – in his case, as a Muslim male. At the Koffler Gallery, His and Other Stories displayed a grand program of large, heavily manipulated, and very funny colour photographic tableaux that illustrated a concocted narrative featuring a community of characters, all played by the artist and many sharing the same Photoshopped frame. Central among them were a hypocritical Muslim priest (Abdul), his traditional wife, and his sexy mistress, enacted by the artist donning, respectively, prayer attire, a veil, and sexy underwear. In a stunning remake of Orientalist Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s La Grande Odalisque (1814), the artist calls up all the stereotypes, then flips them: conflating exotic harem slave with housewife – wearing pink rubber gloves, with a feather duster as fan – he gazes seductively over his shoulder at the viewer. The denouement of the fiction, presented in both video and photographic format, resolves all identity dilemmas in a dramatic moment that references Benjamin West’s The Death of General Wolfe (1770): the murder of the Muslim superego, Abdul, releases all other characters from their chafing identities. As with Lake’s process, 2Fik’s liberation is performed through the creative working through of ideas, process, and materials.

Numerous other exhibitions explored issues related to identity. The AGO’s Free Black North presented nineteenth-century tintype and cabinet-card portraits of ex-slaves and slave descendants who, after escaping via the Underground Railway, formed communities north of the U.S. border. Freed from slavery, but not from Canadian racism and segregation, dressed in their best and posing in formal portrait studios, they insist on respect. Through wall panels and video interviews, visitors were relieved of the tired mythology of a righteous and welcoming multi-cultural Canada. The development of ex-slave black communities was also the subject of Deanna Bowen’s moving video, included in the Royal Ontario Museum’s The Family Camera, that followed Bowen’s road trip to discover relations in similar ex-slave communities in the U.S. At Georgia Scherman Projects, 2017 Gattuso Prize winner Sandra Brewster displayed It’s all a blur…, her large gel-transfer-on-paper portraits of fellow members of the Guyanian diaspora, their blurred faces and sketchy surfaces suggesting fragmented and mobile identities.

Particularly powerful were four videos by Indigenous artists, screened at the RIC in the exhibition Souvenir, that montaged imagery from the National Film Board archives. Interdisciplinary artist Kent Monkman’s work Brothers & Sisters (2015), conflated young victims of the “Sixties Scoop” and their incarceration in residential schools with the mass slaughter of the Plains bison, making a pointed, and moving, indictment of colonial destruction.

The bison appeared again within an exhaustive survey that outlined in shocking detail the history of environmental damage in Canada. In It’s All Happening So Fast: A Counter-History of the Modern Canadian Environment at the Art Museum at the University of Toronto, a mix of documentation and artworks by numerous artists and from media sources gave a disturbing wealth of information concerning every major environmental disaster that has occurred in Canada. One such disaster occurred in 2013, when a New Brunswick Natural Gas facility burn-off killed about 7,500 migrating songbirds. Visitors to the Corkin Gallery saw their burned and charred bodies, photographed by Thaddeus Howlonia against white backgrounds (The Natural Order). Irving Oil Ltd. and Respsol were fined too little for that crime, but the birds’ bodies, now etched onto paper, continue to memorialize and indict. So it is that images can cross, condemn, and unsettle acts of violence and power – including, for example, the mythical assertions of “Canada 150.”

[Full issue available here : Ciel variable 108 – GOING PUBLIC ]

Purchase this article