[Spring-Summer 2018]

By Ariane Noël de Tilly

For twenty years, Vancouver artist Carol Sawyer has constructed a speculative history around her character Natalie Brettschneider, through whom she has introduced the art practices of a number of previously overlooked artists who developed within alternative circles. Sawyer’s initiative, unique and imbued with humour, was born in response to her frustration that almost no documentation and few published studies existed on the work of interdisciplinary women artists – including Emmy Hennings, Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, and Claude Cahun – despite their significant contribution to their respective fields.1 However, instead of undertaking research on these artists in particular and publishing her findings in a scholarly publication, Sawyer chose to invent Natalie Brettschneider. Brettschneider, an interdisciplinary artist born in New Westminster, British Columbia, personifies her feminist critique of the way in which history has too long been written – a history that, as Linda Nochlin wrote in 1971, has ignored the contribution of women artists.2

It was in 1998, during the Re-inventing the Diva festival, presented at the Western Front in Vancouver, that Sawyer first introduced the work of Natalie Brettschneider to the public. Accompanied on the piano by Andreas Kahre, she performed works from the repertoire of this invented artist. Since then, Brettschneider’s life and career have been revealed in fragments through photographs, essays, films, performances, and even a constantly growing archive. Each exhibition, solo or group, has become an opportunity for Sawyer to invite the public to take a new look at different periods in Brettschneider’s life and those of the artists she may have met. A talented singer, Brettschneider performed in several operettas and then received a scholarship to study singing in Paris in 1913. To make ends meet, the young Canadian obtained a contract with the department store La Samaritaine, for which, every Saturday, she demonstrated an antiseptic gargle in the basement. Because the performances were very popular with the Paris avant-garde, management put an end to this collaboration in 1915. After developing her art within various groups of avant-garde artists in the 1910s, 1920s, and 1930s, Brettschneider had to return to Canada in 1938 to care for her mother. The following year, she spent time in the Okanagan Valley; in the 1940s, she lived in New York, where she made a name for herself in jazz circles. However, suspected of being a communist sympathizer, she was forced to return home.3 Little is yet known about her life between the 1960s and 1980s.

In the last two years, the touring exhibition Carol Sawyer: The Natalie Brettschneider Archive has been presented at the Carleton University Art Gallery (2016), the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria (2016), and the Vancouver Art Gallery (2017– 18). Its journey will end in Windsor in 2019. At each stop, the exhibition has expanded as Sawyer takes the opportunity to uncover archives on site and reveal new information and testimonials on Brettschneider’s life. Each iteration of the project therefore takes on local relevance and enables the public to discover artists and other cultural actors in each locality. For example, through searches in the archives of the Carleton University Art Gallery, the National Gallery of Canada, and the collection of Library and Archives Canada, Sawyer spotted moments when Brettschneider’s career apparently crossed with that of Frances Duncan Barwick, a harpsichordist who studied music in England and lived in Paris between 1926 and 1938, and that of her brother Douglas Moerdyke Duncan, a bookbinder and director of the Picture Loan Society in Toronto. In Victoria and Vancouver, Sawyer was able to draw attention to the works of women artists who had been members of the first cohort of the Vancouver School of Decorative and Applied Arts, including Vera Weatherbie and Irene Hoffar Reid.

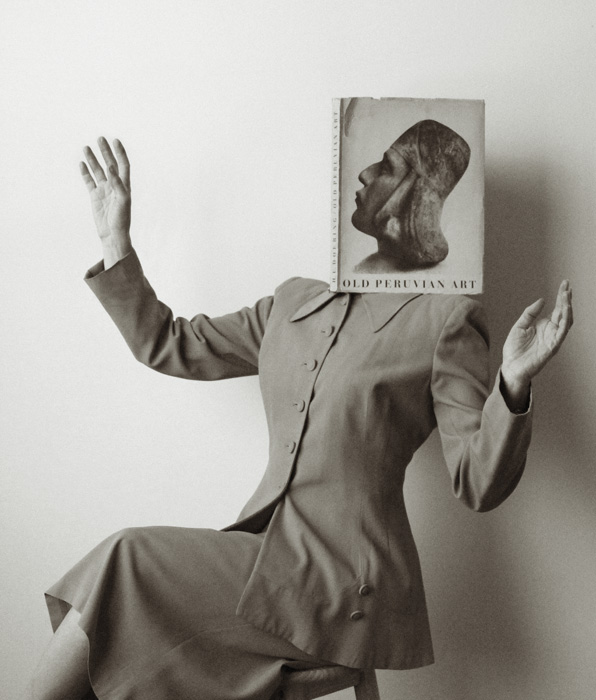

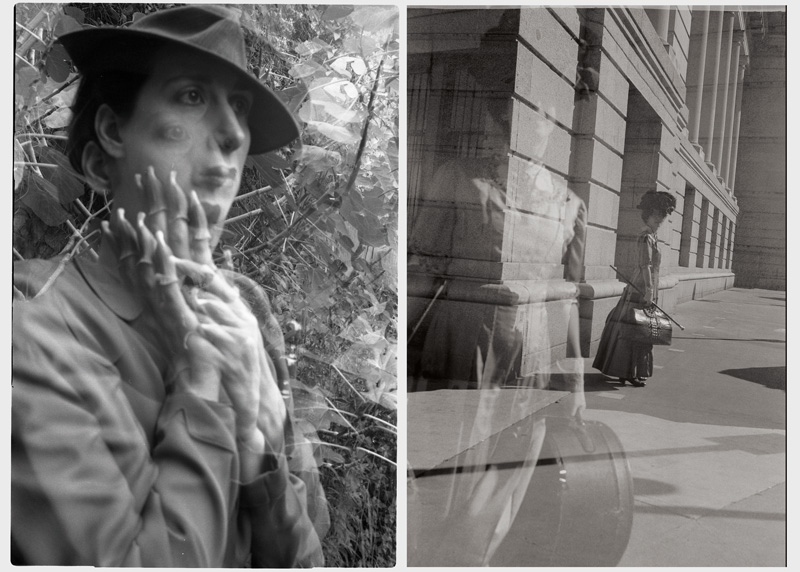

The narrative built on Brettschneider’s life and career transports us into a fascinating visual and musical world. The colourful personality that Sawyer has invented is manifested differently in the fields of photography and performance. Sawyer poses as Brettschneider in photographs; during performances, however, she does not play the character, who passed away in 1986, but instead performs a repertoire inspired by her work. In this very rich narrative, Brettschneider is never presented as “the wife of,” “the mistress of, or “the muse of,” in the way that so many women artists, including Kiki de Montparnasse and Sonia Delaunay, were initially introduced in the literature. The perspective that Sawyer favours instead is that of focusing on work, creativity, collaboration between musicians and artists, and the mingling of various disciplines. In the many photographs featuring Brettschneider’s musical activities, Sawyer asked her family and other people she has met while working on the project to contribute to her narrative. And so, curator Heather Anderson, armed with a pot cover and a mallet, plays a musician (Natalie Brettschneider and unknown music ensemble at the Booth family residence, Ottawa, c. 1947); artist Geoffrey Farmer, with a casserole on his head, poses as a percussionist (Natalie Brettschneider and music ensemble, the Banff Centre for the Arts, c. 1951); and philosopher and activist Franco (Bifo) Berardi prepares to play the piano (Natalie Brettschneider and unknown pianist, the Banff Centre for the Arts, c. 1951). All of these photographs are documentation of Brettschneider’s musical performances, and the film The Rehearsal, made in 1948 with Maja von Derenstahl, then restored by Carol Sawyer and Evann Siebens in 2015, gives a glimpse of Brettschneider’s diverse performance repertoire.4

Among the musical instruments appearing in the photographs and played in the films are an Electrolux vacuum cleaner, a saw, hammers, mallets, bowls, pots, and a blender. Some of these photographs clearly indicate that the ensembles were performing music, whereas others evoke a performance by their title, including Natalie Brettschneider Performs “Feather Hat,” Montreal (c. 1950) and Natalie Brettschneider Performs “Rapunzel and Medusa sit to talk about war” (c. 1947). Nevertheless, these images might easily be taken for fashion photographs, as the musician is always elegantly dressed and wears a series of ever-more extravagant hats. By giving the photographs titles that evoke rather than describe performances, Sawyer encourages the public to imagine them and therefore to contribute to her narrative. Further, she offers viewers an opportunity to reflect on the different possible ways of telling a story. By interweaving real and fictional histories, she reminds us that history is composed of fragments, that each archival collection is incomplete, and that spaces exist between each image and each document leaving room for interpretation, and even invention, of a narrative.

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 Linda Nochlin [1971], “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?,” in Women, Art, and Power and Other Essays (New York: Harper & Row, 1988), 145–78.

3 Brettschneider’s stay in New York is mentioned in the short biography that Sawyer wrote for the catalogue for the exhibition Facing History: Portraits from Vancouver held at Presentation House Gallery in North Vancouver in 2001. This more political aspect of Brettschneider’s life has not been addressed since. In subsequent exhibitions, the emphasis has been on her interdisciplinary practice and the different art circles of which she was a part.

4 As Natalie Brettschneider is the alter ego of Carol Sawyer, Evann Siebens, who co-directed the film with Sawyer, invented, in tribute to the filmmaker Maya Deren, the fictional artist Maja von Derenstahl.

Ariane Noël de Tilly holds a doctorate in art history from the University of Amsterdam and has been a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the University of British Columbia. Her research deals with the exhibition, dissemination, and preservation of contemporary art, and the history of exhibitions. She is a lecturer at Emily Carr University of Art + Design in Vancouver and the coordinator of the Thirteenth International Conference on the Arts in Society, which will be held in Vancouver in June 2018.

Carol Sawyer is a visual artist and singer working primarily with photography, installation, video, and improvised music. Since the early 1990s, she has explored the connections between photography and fiction, performance, memory, and history. She performs regularly with her improvisational ensemble ion Zoo (with which she has released three CDs) and with other ad hoc ensembles. She is represented by Republic Gallery, Vancouver. carolsawyer.net

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 109 – REVISITER ]

[ Individual article in digital version available here: Carol Sawyer, The Natalie Brettschneider Archive – Ariane Noël de Tilly, Between Fiction and Reality: How to Shed Light

on Artists Who Have Been Left in the Shadows ]