[Spring-Summer 2018]

National Gallery of Canada, Canadian Photography Institute Galleries, Ottawa

Curated by Luce Lebart

November 3, 2017 – April 2, 2018

By Johanna Mizgala

During a ten-year period that began in 1848, the rush to California in the mad hope of striking it rich was intertwined with the burgeoning ability to make a living through the new technology of photography. The mythology of the moment in the West, with its complicated and complex strata of mass migration, forced relocation or outright decimation of Indigenous communities, market economics, and exploitation, is situated historically deep within the rare, storied tales of success and incredible wealth that spurred the creation of the daguerreotypes of these now anonymous individuals, their names long forgotten although their faces persist by virtue of these visual traces of the past. In spite of these traces, their individual histories are as rare and fleeting as the gold veins that drove them to these locations in the first place. It is difficult to know what to make of these small, almost magical portraits of unnamed individuals. The exhibition is composed primarily of images of young, white men who would appear, based on their clothing and the rudimentary settings that form their backdrops, to be carving out a meagre existence in mining camps and makeshift settlement communities. It is far too easy to fall into the trap of romanticizing their lives, as the portraits are exquisitely beautiful and some are even toned with gold, the very metal that drew them all to the West.

In the exhibition catalogue these men are referred to collectively as “Argonauts” – a reference not only to the Argonaut Mine in Jackson, California, but also to Jason and the Golden Fleece. To be swept away in the romance and bravado of the quest for gold as told visually in a context so far removed from the gruelling circumstances of their creation is to risk falling prey to a wilful blindness, almost in the same manner as the subjects themselves, who were spurred on by tales of overnight success and tremendous wealth.

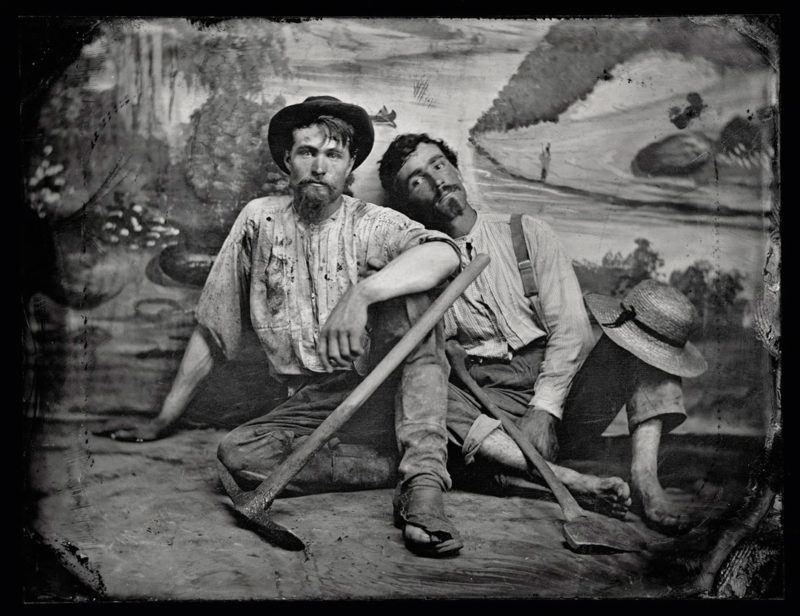

One particularly poignant portrait, reproduced not only as the cover of the catalogue but also in a larger-thanlife two-page spread, is a quarter-plate tintype by an unknown photographer, depicting two men described as prospectors. They sit on the floor in front of a serene painted landscape backdrop. One man is barefoot and the other might as well be – his toes poke through a gaping hole in his boot. Their posture speaks to an intimate connection to one another, but we don’t know the circumstances – they could just as easily be brothers or lovers. They stare out directly from the image, holding the viewer’s gaze. The portrait is arresting precisely because all that we can ascertain about the subjects comes from trying to read the clues in the image. It is unsatisfying and unsettling, because we want to know more, but likely we never will.

The exhibition contains a few scenes and landscapes that do convey a bit more information, mostly about the technology used for extracting gold from the rock, the living conditions and daily existence of the workers, and traces of interactions among classes, cultures, and communities. A daguerreotype by G. H. Johnson, one of the rare named photographers in the exhibition, shows a view of a mining operation on the North-Folk American River, in northern California. A man in the foreground is obviously posing for the photographer. He holds the hand of a young girl, whose face is blurred because she moved during the exposure time required to capture the scene. In her other hand, the girl holds something that may be a doll. This image, as well as the one of a woman seated in a wagon in front of a daguerreotype studio, underscore for the viewer that these wild places were not just the domain of young, brash fortune seekers, but were also the homes of families, who clung desperately to the hope that their time on this terrain would ultimately yield a better life for them.

Daguerreotypes and their cousins, the less expensive ambrotypes and tintypes, were private images, cherished reminders of those separated by time and distance. They were often mailed home to loved ones, and delivery was part of the commercial services offered by portrait studios. The correspondence included in the exhibition, along with some of the images still in their protective carrying cases, speak to their exchange and to their deep personal value. Prior to the invention of photography, portraiture was simply unavailable to a wider audience, and typically the domain of the very wealthy.

The images are startling because they provide evidence of the beginnings of democratization of the portrait, and well as offering some insight into the lives of those who so often remain anonymous. Notwithstanding the seductive powers of the “mirror with a memory,” we still know little about the individuals who stare silently out at us from the gallery’s walls. They played a part in a larger, epic story, but their individual voices remain silent.

Gold and Silver is organized by the Canadian Photography Institute of the National Gallery of Canada, in partnership with Library and Archives Canada. This exhibition was made possible thanks to the gift of the Origins of Photography Collection made by the Archive of Modern Conflict.

Johanna Mizgala is the Curator of the House of Commons and is currently working on a biography of Canadian architect John A. Pearson (1867–1940). She has lectured and published extensively on contemporary and photo-based art and has curated numerous group and solo exhibitions over the past twenty years. She is a member of the board of directors of the School of the Photographic Arts in Ottawa.

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 109 – REVISITER ]

[ Individual article in digital version available here: Gold and Silver, Images and Illusions of the Gold Rush – Johanna Mizgala ]