[Spring-Summer 2018]

VU Photo, Quebec City

October 27–December 3, 2017

By Robert Anderson

If you think the title of Laotian-born, Canadian-raised artist Kotama Bouabane’s recent show at VU, We’ll get there fast and then we’ll take it slow, sounds suspiciously like a lyric from a bad pop song, you’d be right. The title is from the song “Kokomo” by the Beach Boys. By the time of this late-career hit, about an imaginary tropical paradise, the group of middle-aged musicians had long become a pastiche of the youthful, idealistic, American culture that spawned it. Bouabane references the song as part of a critique on the institutionalization of “official culture,” while acknowledging, as an artist, his inevitable complicity in the construction of Western discourse. The failure of discourse to represent identity and culture outside of the homogeneous dominant ideology is foregrounded in his discursive strategy. His subversive and discursive weapon to challenge this ideology: a coconut.

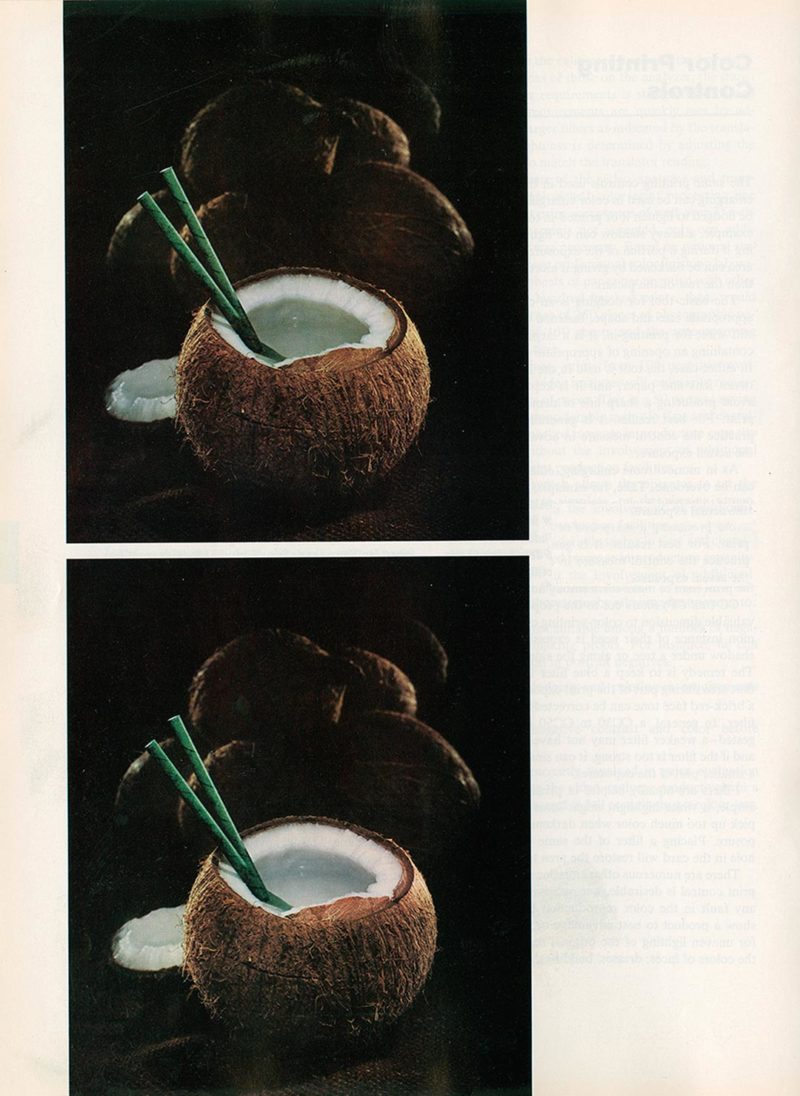

CC50G is the title of Bouabane’s appropriation of a page from an old Kodak manual on how to colour-correct photographs. It shows an example of a photograph printed twice: one has a green tint; the other is colour corrected. But the object photographed for the demonstration signifies ideological assumptions for the intended reader. Kodak uses a cracked-open coconut, with two plastic green drinking straws inserted, to represent the West’s view of the exotic Eastern world, which apparently waits to be discovered by tourists and captured on Kodak film. Bouabane emphasizes the complicity of corporate American and the media in the continuous construction of orientalism – post-colonial scholar Edward Said’s term for how the East is defined and (mis)represented by the West.

The most visually dynamic series in the show is fifty stark black-and-white photograms. When Bouabane places a half coconut shell on photographic paper, the resulting photogram is a white circular object against the black exposed paper, visually reminiscent of a full moon in the night sky. On closer inspection, we find that Bouabane has drilled three holes in the shell, following its outer indentations. The holes print as small, round black objects, configured as two eyes and a mouth. The amusing result is a surprised-looking face gazing back at us. We may well ask, who are these anonymous little faces, apparently shocked by being represented here?

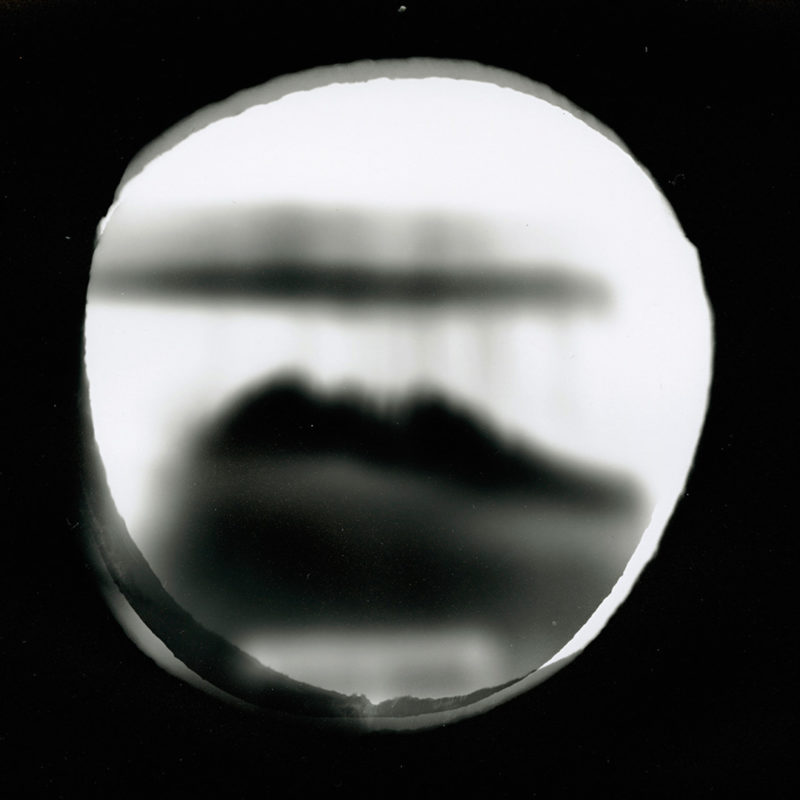

Referencing the origins of photography, Bouabane uses a half coconut as a makeshift pinhole camera. His ostensible subject is the Canadian landscape, long mythologized by Canadian artists and synonymous with the creation of Canadian identity. But in Bouabane’s analogue prints, the results are blurry and extremely expressionistic. Although engaging in their own way, the prints suggest the impossibility of ever finding a singular, coherent Canadian “voice” unmediated by discourse.

An almost-life-size colour photograph, featuring the artist, questions the ethnographic narrative. The colonial subject of Laotian ancestry, represented by Bouabane’s presence in the photo, stands proudly on a mountaintop with the Canadian Rookies in the background, approximating the modern-day selfie, with a coconut, mimicking a camera, mounted on a long wooden pole. Self-representation becomes a means to usurp the photographic discourse and its historical claims of portraying “objective” truth, most notably famed nineteenth-century British photographer Francis Frith and his work that glorified the colonial presence in the East, justifying imperialism for the masses.

Coming from speakers inside a gigantic coconut sculpture, Bouabane’s rudimentary musical performance on a khene, a traditional Laotian instrument, can be heard playing the tune of – you guessed it – “Kokomo.” The French colonization of Laos is represented by fake baguettes and cut-outs of Laotian patterns, found in the National Geographic black sand surrounding the coconut. The brand of aquarium sand shares its name with the venerable magazine, which situates itself as an authoritative narrator of the East, and other “exotic” regions, for Western audiences. Shining out of the giant coconut, green lights reference the “uncorrected” colour cast of the coconut from the above-mentioned appropriated Kodak manual. These endless associative constructions are enough to cause cultural psychosis in the viewer.

While the surf has long gone out to sea for the Beach Boys, We’ll get there fast and then we’ll take it slow inspires important culture questions (what is a community’s right to self-representation?) and raises the work far above a pastiche of the postmodern world. Bouabane’s absurdist humour serves the intent of his work perfectly, as he theorizes and creates a coconut as a rhetorical device that foregrounds its own rhetorical status in the discourse. For Bouabane, identity is performative, as well as historically and socially constructed. By acknowledging the limitations of representation in discourse, the art of Kotama Bouabane becomes the act of becoming.

Robert Anderson holds an MA from York University. He has written reviews and articles for such art and literary publications as Canadian Art, The Puritan, and Fjords Review. His art photography has been widely seen in Toronto galleries and published in BlackFlash Magazine and The Toronto Quarterly. His poetry has been published in such journals as Rampike, b after c, and House Organ. He has a poetry chapbook The Hospital Poems (Bookthug).

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here : Ciel variable 109 – REVISIT ]

[ Individual article in digital version, in French only, available here : Kotama Bouabane, We’ll get there fast and then we’ll take it slow – Robert Anderson ]