[Fall 2019]

By Jill Glessing

Violence runs through our lives, experienced directly or through media representations. We are subject to its power to varying degrees depending on our geographical location, race, class, gender, and access to high-speed internet. We are well acquainted with the variety of ways that humans inflict harm – whether physical, social, or psychological – upon one another. It is not odd, then, that violence appears as a prominent thread within a photography festival. After all, it has been an enduring subject in photography, represented in the medium even before the technology could freeze motion. Despite the absence of actual battle in Roger Fenton’s propagandistic Crimean war scenes, the images clearly referenced the destruction; similarly, ethnography pinned the vulnerable, often naked, bodies of its subjects onto photographic papers and plates, forcing their permanent exposure to the racist imperialist gaze. No such uses appeared in the 23rd edition of Toronto’s CONTACT Photography Festival;1 instead, the featured artists used the medium to analyze and critique violence within a range of contexts.

Among them, celebrated African American artist Carrie Mae Weems, who enjoyed a spotlight this year with exhibitions in two venues and three public installations, provided the broadest view. Heave, at the Art Museum at the University of Toronto,2 scanned the turbulent history of Weems’s own country’s infliction of pain around the globe, beginning with the last gasps of the Second World War. Through video, photography, and installation, Weems took us through that sad history to show, beyond the borders of the United States, the horrors of Hiroshima and Vietnam and, inside the country, a list that included segregation, the civil rights movement, student protests, and political assassinations, bringing us to the ongoing police violence against black men.

Each of the exhibition’s three sections staged social spaces and institutions in which different kinds of cultural discourses occur: the classroom, the living room, and entertainment theatre. The first, Constructing History: A Requiem to Mark the Moment (2008), a photography and video installation, developed out of Weems’s projects with students that used performative models of education. Our consumption of tragic news reports may incite sympathy, but it often fails to produce an empathy that triggers action and change. When Weems and her students re-enact those historical tragedies and occupy interchanging positions of victim and perpetrator, they may understand the dynamics of violence more deeply. In the twenty-minute video, students create tableaux of monumental poses and stricken expressions, accompanied by Samuel Barber’s mournful Adagio for Strings, Op. 11, bringing viewers to understand their own implication in and responsibility for the future. In one particularly moving scene, a young black woman stands in a white Japanese kimono, snow falling softly around her threatening to erase memory and obscure history. Turning slowly, she scans the past and looks toward the future, as Weems narrates in a voiceover, “But to get to now, to this moment, she needs to look back over the landscape of memory. Lost in memory, the woman faces history. . . . If you look on the horizon here and there, first seen, now hidden, are little sightings of hope or dreams or memories. If you look closely through the corridors of time, even within the horror one could see the fluttering wings of doves, wings like time batting out beats of hope.” Unlike Walter Benjamin’s “angel of history,” who looks into the past and sees only the endless piling up of catastrophe, Weems’s angel peers into the morbid depths and finds glimmers of promise.

Another of the video’s tableaux re-creates Eugene Smith’s moving photograph Tomoko Uemura in Her Bath (1971), which captured a mother bathing her daughter’s mercury-ruined body. Weems’s version refers not only to the corporate greed that poisoned fish in Minimata Bay, Japan, and the people that ate them, but also to the irradiated victims of the U.S. atomic bomb dropped in nearby Nagasaki. Again, Weems recuperates the dark history of the United States. It is that very lineage of horror “that made it possible for us to actually begin to have these conversations. So now, fifty years later, we are now saying yes, we are finally ready to sit down and deal.”

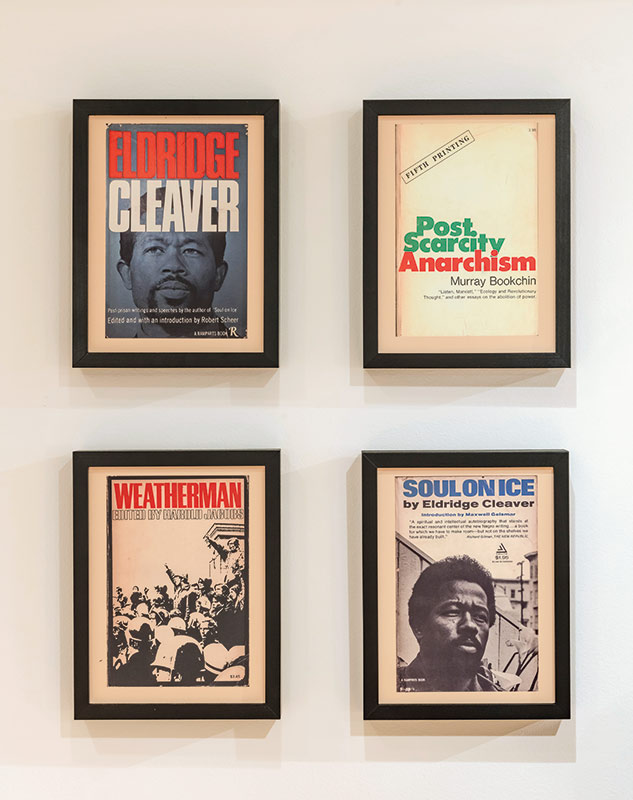

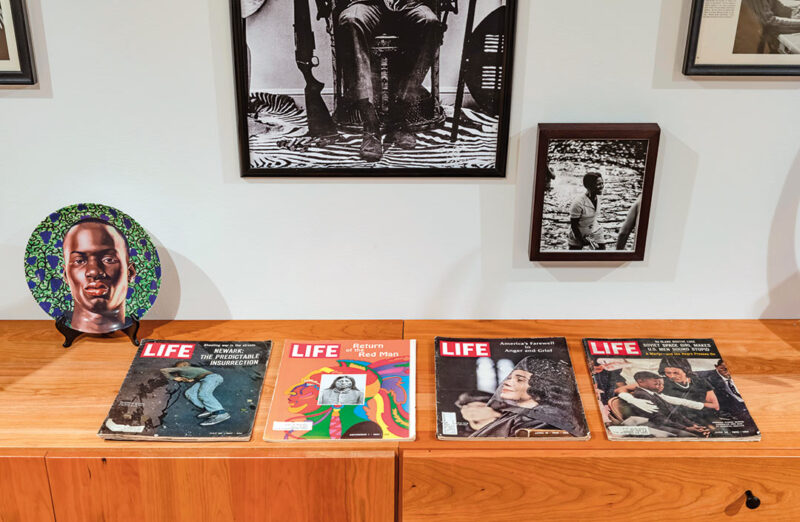

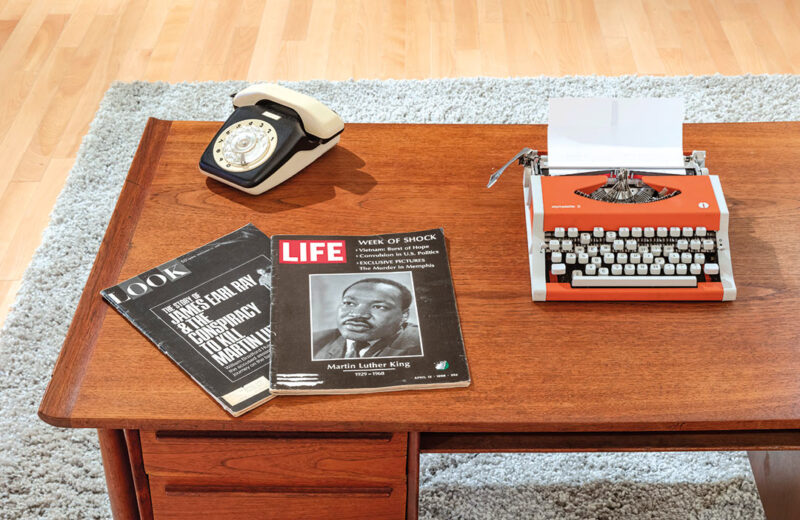

The second room is furnished as a 1960s-era living room filled with archival materials – framed photographic images, a functioning turntable and record collection, a small black-and-white television set, and ornaments and sculptures that refer to figures and events important in the civil rights and Black Panthers movements, such as Angela Davis and Bobby Seale. Sitting in comfortable chairs, viewers could peruse the coverage of assassinations of a shockingly long list of political figures – among them John F. Kennedy, Medgar Evers, and Malcolm X – in the vintage LIFE magazines stacked on a coffee table or play video games. Repeating Weems’s promotion of individual agency and responsibility, visitors could choose from two games offered: one that was programmed as violently aggressive and the other offering interactive possibilities for non-violent resolutions.

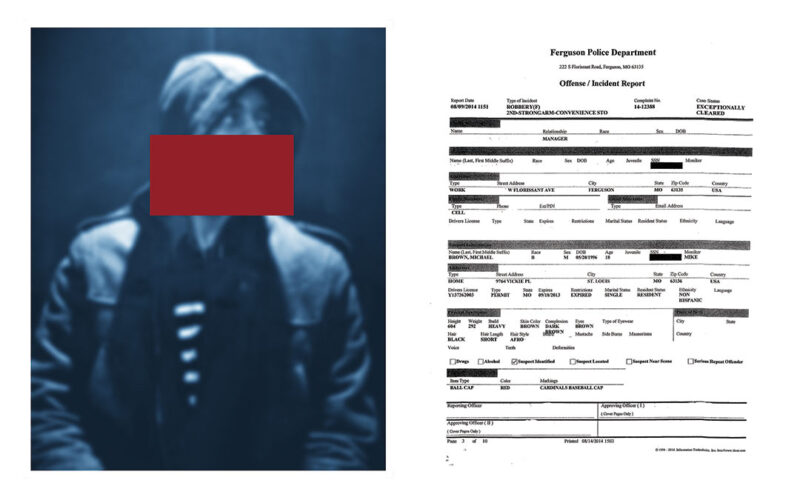

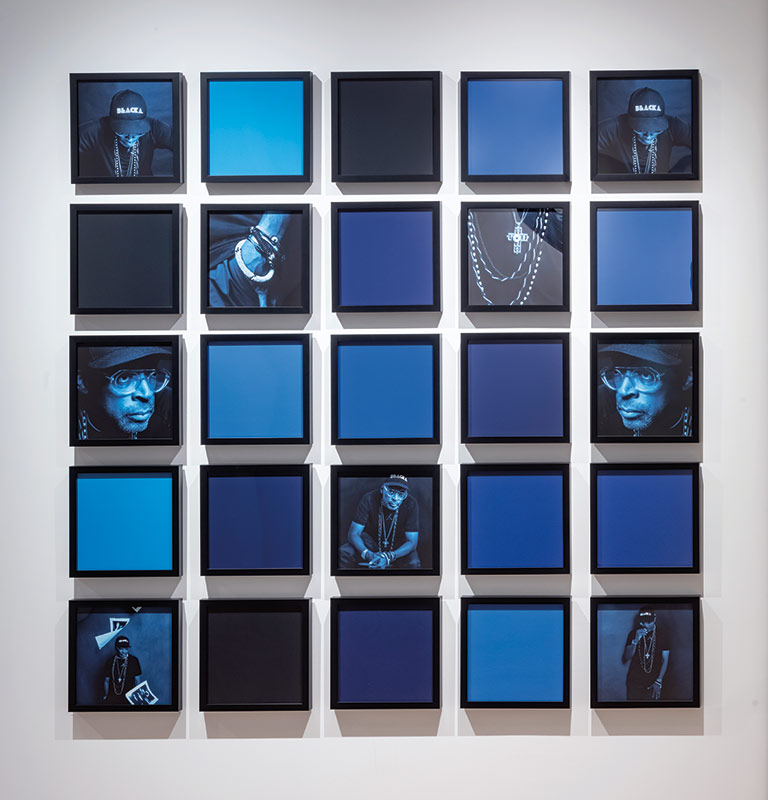

At the CONTACT Gallery, Weems’s more contained exhibition, Blending the Blues,3 focused on current African American culture. Here, too, the large photographic works offered a mix of tragedy through images of police violence, but also hope, through more positive images of celebrated black cultural figures, such as Spike Lee and Dinah Washington. All the Boys (2016) presents enlarged, blue-tinted mug shot–style photographs of black youths paired with police reports detailing physical attributes, crimes, and the outcome of police interactions – death. Weems deconstructs the pure phenomenon of colour that has been coopted by hierarchical power systems to signify racial value. Colour plays upon all her subjects – through either rectangular blocks of primary colours superimposed over their portraits or a full tinting of the image with softer shades. Again, Weems’s defiance of racism’s sad legacy intervenes in the violent colour binary of black and white. Playfully diversifying colour across her subjects, she rejects the hard categories imposed by white power.

The violence broadly surveyed by Weems bled into more focused subjects in other exhibitions. Western countries, and particularly the U.S., perpetrate violence around the world directly through invasion and indirectly through the arms trade. From the continual flow of violent media imagery consumed by Western audiences, we know that most of this activity occurs in Islamic regions. Three artists bound to these struggles through heritage and homeland offered alternate images that reveal more personal experiences and critical perspectives.

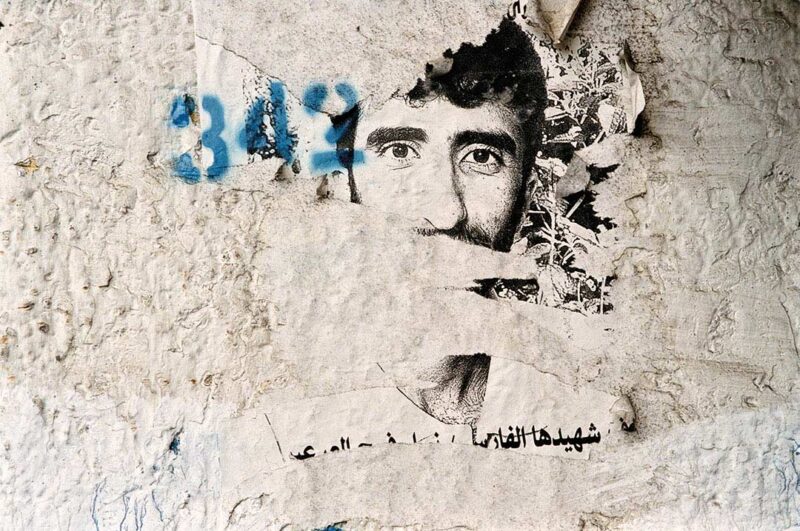

Suspended Time presented a mixed-media exhibition of photographs and installations at Prefix Institute of Contemporary Art.4 Artist Taysir Batniji lives in France, but, like other members of the Palestinian diaspora unable to return, his heart and work continue to dwell in Gaza and on the pain of losing people close to him through death and displacement. During the Second Intifada, photographs of those killed while struggling against Israeli occupation were posted on walls. A series of ten large colour photographs, Gaza Walls (2001), documents these public memorials. Their painterly surfaces, signifying Batniji’s transition from his earlier painting practice to photographic media, show remnants of the lost faces that doubly decompose beneath layers of graffiti and other posted materials. To My Brother (2012), inspired by the practice of sketching Gazan street violence and, as protection, erasing the drawings, similarly links drawing and photography. To commemorate Batniji’s brother, who was killed by Israeli soldiers, the artist printed negatives from that brother’s wedding and then, laying the prints over white paper, traced the outlines of the celebrating figures. The faint, almost indiscernible indentations created by the pressure of the drawing instrument created a ghostly impression, evoking memory and separation.

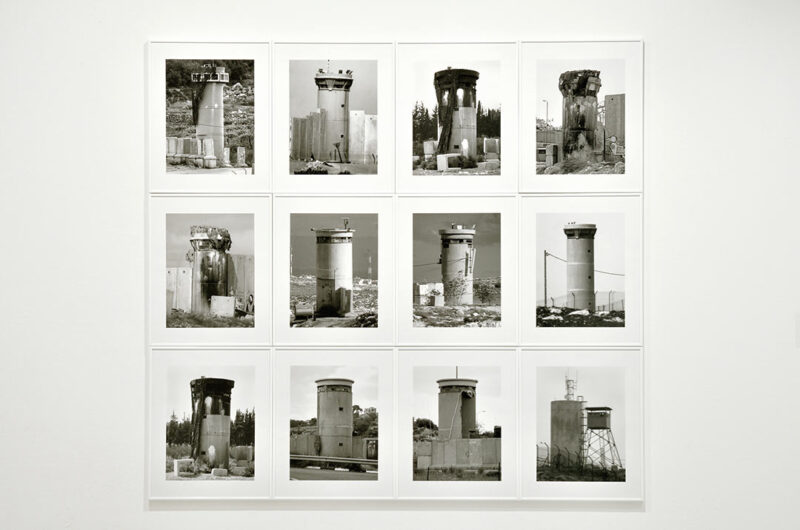

Two other works rely on established photographic formats – the art world and the real estate market. Watchtowers (2008) remakes Bernd and Hilla Becher’s signature typological series of outdated industrial infrastructure and, in particular, Water Towers (1972–2009). Batniji’s installation duplicates the Bechers’ format – small, black-and-white, framed, technically perfect photographs of architectural structures arranged in a grid – but expectations give way as viewers gradually note differences from the original models: here, Israeli military guard towers replace benign water tower relics; technical and aesthetic precision and uniformity are absent. Unable to return to Gaza to shoot his subject himself, Batniji relied on a Gazan resident who could only quickly, under duress and risk, make blurred, imprecise exposures. The images are thus stamped with Batniji’s own dislocation.

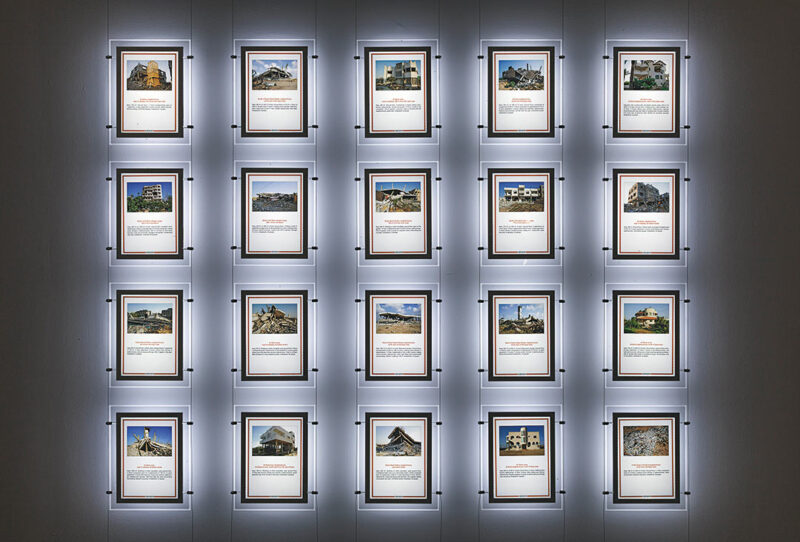

GH0809 (2010) similarly adheres to a grid-like arrangement, but in this case, following the format of real estate window displays, photographs are set into an acrylic framing structure. As with Watchtowers, expectations of normalcy are thwarted when one sees that the buildings for sale are bombed-out Gazan homes and apartment buildings, most no longer habitable. Beneath the images, short texts in the promotional language of real estate description offer such details as “North of Al-Shati refugee camp, 200 m from the beach, Open sea view, calm and sunny, Beautiful exposure, 3 balconies, near to schools. Inhabitants: 22 people.” It’s understood that those who once resided there and enjoyed those beaches and views are now either deceased or displaced.

Two other artists combine traditional Middle Eastern textile design, photography, and military technology in their works, inserting photographic images into Islamic patterned fabrics. Nevet Yitzha, an Arabic Jew living in Israel, identifies with her family’s diasporic history throughout Middle Eastern regions, including their weaving traditions. Yitzha’s Koffler Gallery exhibition WarCraft5 is based on Afghan war rugs, a design innovation that began during the Soviet invasion. Three wall-size digital projections of carpets heavily decorated with an array of animated military equipment – tanks, armoured vehicles, grenades, rifles, and helicopters – appear at first as harmless video games, but standing within these walls of war, seeing and hearing fighter jets soar, sirens wail, bombs being released, and tanks exploding in sudden flame, one can imagine the terror and trauma of a real war zone. As a marginalized Arabic Jew in hierarchical Israel, Yitzha offers WarCraft as a not-so-veiled critique of her country’s military aggression against her Palestinian neighbours, with whom she identifies.

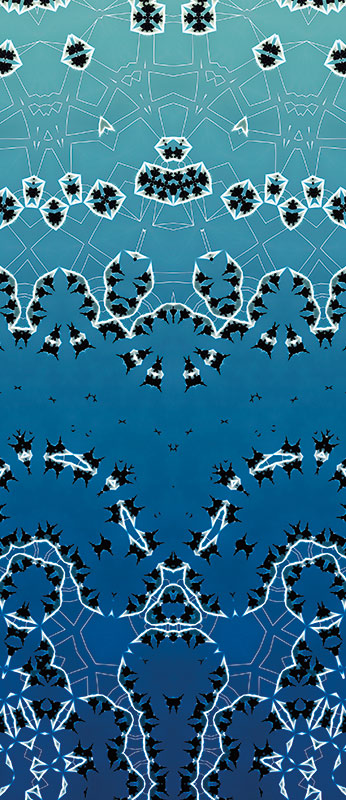

Most of the world’s increasingly sophisticated weaponry originates in Western countries, including the United States, Britain, and Canada, which receive considerable economic value from their production contracts. These weapons’ deadly effects, however, are often destined for Middle Eastern regions. Iranian-Canadian artist Sanaz Mazinani links these disparate worlds in her photo-textile project Not Elsewhere (2019).6 Mazinani appropriates digital images of fighter jets from the Internet, embeds them into decorative patterns reflective of Arabic design, and prints the kaleidoscopic imagery onto long fabric banners. In pretty shades of blue, purple, and white, they hang draped from the high ceilings inside the Aga Kahn Museum atrium. The light, airy patterns suggest blue skies and white clouds undarkened by threatening bombs.

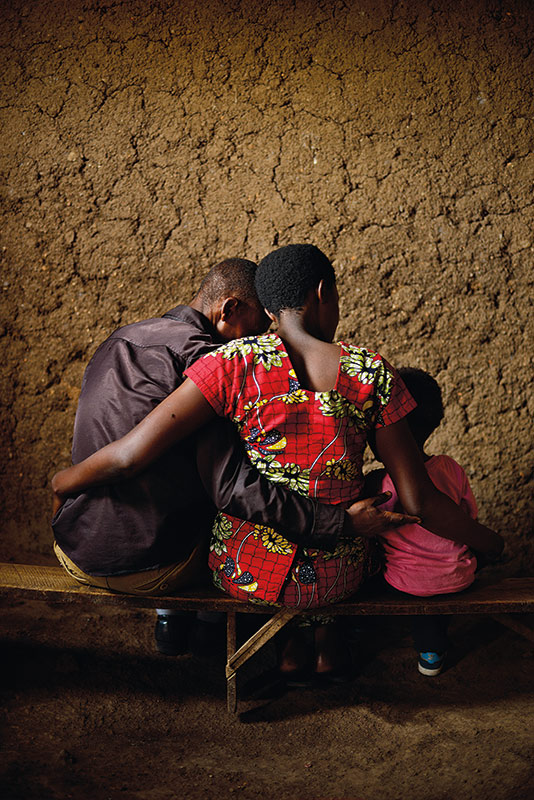

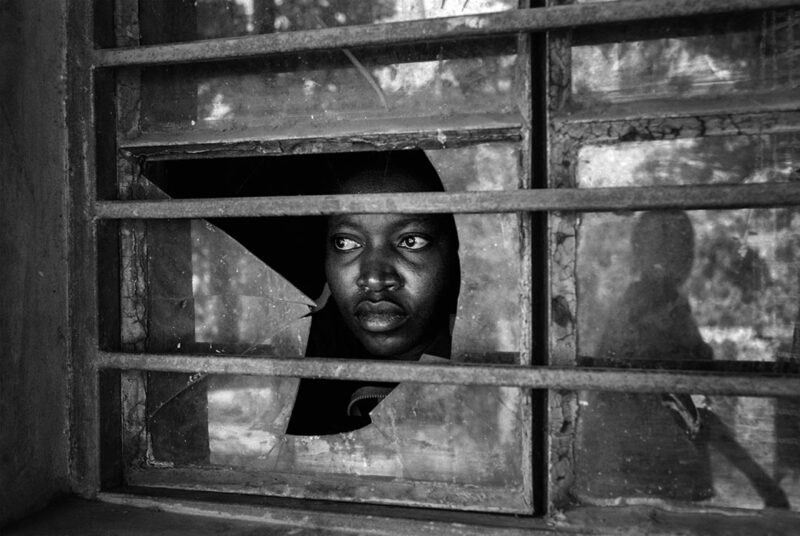

We’re aware of the varieties of human violence and its yield of trauma, but less familiar with positive responses to it. Enduring violence is difficult, but its aftermath – physical and psychic scars – can be unbearable. At Hart House, University of Toronto, a series of photographs, Rwanda Retold: The Enduring Stories of Genocide Survivors,7 displays the courageous efforts of women who survived the Rwandan genocide (during which 250,000 to 500,000 Tutsi women and children were raped), to reconcile their memories of rape, torture and death. Each of Samer Muscati’s large colour portraits presenting an individual or group of smiling women is accompanied by quotations describing their details of traumatic experience and their recovery process. Destruction of bodies, lands, and societies through wars and police violence are obvious forms, but lives can also be violated by controlling spatial relations. Of growing concern, as wealth and power concentrate in urban centres, are the effects of development, gentrification, and displacement on lower-income local populations. Ethiopian photographer Michael Tsegaye documented the destruction of homes and communities in his home city of Addis Ababa and their replacement with foreign-funded development projects. In his Black Artists Networks Dialogue Gallery exhibition Future Memories,8 Tsegaye shows the city’s transformation: razed buildings, new construction, and the displaced standing before their destroyed homes. He also photographed the city’s cemeteries before they, too, were bulldozed for redevelopment. In Tsegaye’s culture, grave markers are often graced with photographs of the deceased. A series of twenty colour photographs that he made of these images were presented in an intimate upstairs gallery. Like the bodies they commemorated, they were in varied states of ruin and decomposition. Roland Barthes famously wrote that all photographs signify death. These pictures appear as a deathly mise en abyme: the subjects’ bodies, their resting places, and their photographs are all violated and destroyed.

The different subjects, perspectives, and formal approaches presented in these CONTACT exhibitions alerted audiences to destructive power systems operated through direct physical damage, as in war and state violence or, more subtly, to solidify social and economic hierarchies – destruction through bullets or social murder. The artists featured perform important social roles in their examination and critiques of violence and, at times, their responses of hope and resistance.

2 Curated by Barbara Fischer and Sarah Robayo Sheridan, the exhibition Heave was presented 4 May–27 July 2019

3 Curated by Bonnie Rubenstein, the exhibition Blending the Blues was presented 1 May–27 July 2019.

4 Taysir Batniji’s exhibition Suspended Time was curated by Scott McLeod and presented at Prefix ICA 3 May–22 June 2019.

5 The exhibition was curated by Liora Belford and held 4 April–26 May 2019.

6 Mazinani’s project Not Elsewhere was presented at the Aga Khan Museum 30 April–2 June 2019.

7 Curated by Sarah Milroy, Rwanda Retold: The Enduring Stories of Genocide Survivors was held 1 April–31 May 31 2019.

8 Michael Tsegaye’s exhibition Future Memories & Chasms of the Soul: A Shattered Witness was presented at BAND Gallery 25 April–2 June 2019.

Jill Glessing teaches at Ryerson University and writes on visual arts and culture.

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 113 – TRANS-IDENTITIES ]

[ Individual article in digital version available here: CONTACT 2019. Violence — Jill Glessing ]