[Winter 2020]

An interview by Jacques Doyon

Jacques Doyon: What is the origin of the work Aleppo, Syria December 17, 2016? How did the idea emerge? Why Syria? And what prompted you to work from an existing image of a disaster?

Gisele Amantea: I was invited by curator Emily Falvey to participate in the group exhibition Here Be Dragons. The theme of the exhibition, which took place at Carleton University Art Gallery in Ottawa in the fall of 2018, was to present the work of artists who “explore a range of contemporary art practices engaged in social critique and strategies of political resistance that deploy ambiguous, symbolic images to summon active interpretation on the part of the viewer.”1 Emily was interested in having me create a site-specific work for a particularly large, challenging space in the gallery. The invitation appealed to me for two reasons. First, I have made many ephemeral, large-scale site installations in which I sought to transform the viewer’s experience by altering what I came to think of as the “skin” of the architecture. These works were immersive – made directly on the surfaces of specific spaces in galleries and museums. Second, these works have been intended to provoke viewers, physically and psychologically, to consider pertinent social and political issues.

I had visited Aleppo in 2010, and in developing a work for Here Be Dragons I initially thought of an environment that reflected upon the civil war in Syria and the migrant crisis that had resulted from it. At the time, I began to look at what seemed like a never-ending circulation of images of death and destruction, primarily of those who had drowned at sea or were affected when large areas of Syrian cities had been bombed to near-complete ruin. In my research I came across a critique of war photography in the New York Times by Michael Kimmelman, who argued that the flood of these images risks “normalizing indifference” to the tragedy that they are intended to convey.2 At the same time, photojournalists in Syria were questioning whether daily posting of their images made any difference, and the art collective Abounaddara asserted that the images denied Syrian people their diversity.

In contemplating these images, I could not help but think about empathy. Was it useful? What made some so devoid of it? I also became aware of the work of Ariella Azoulay, her discussion of conflict photography, and in particular her book The Civil Contract of Photography (2008), in which she writes about the need to “watch” rather than “look at” photographs as part of the responsibility to their subject. I found the implication that one needs to be active rather than passive when looking at these photographs especially resonant.

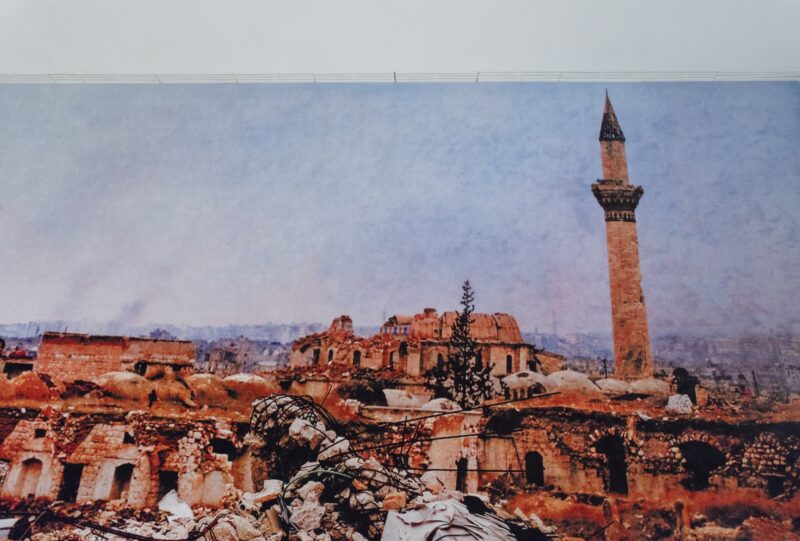

In the course of this process, I came across an image of a bomb site in Aleppo that particularly struck me. It was a photograph taken on December 17, 2016 for Reuters by Omar Sanadiki, a Syrian photographer living in Damascus. The photograph documents the destruction of the Citadel Hotel in Aleppo on that day. Although rich in detail, the large landscape vista of the devastation was completely devoid of human life. This enabled me to imagine how I might make those visiting the gallery become a critical, active element in the work.

JD: Aleppo is meant as a site-specific work, in terms of the experience it is offering to the visitor. It is set within a specific art gallery, it proposes a physical, if not architectural, interaction to the photographic image, and it is based on a transfer of media that implies a number of cultural displacements and confrontations. Would you tell us more about the experience and challenges that you are proposing to the viewer?

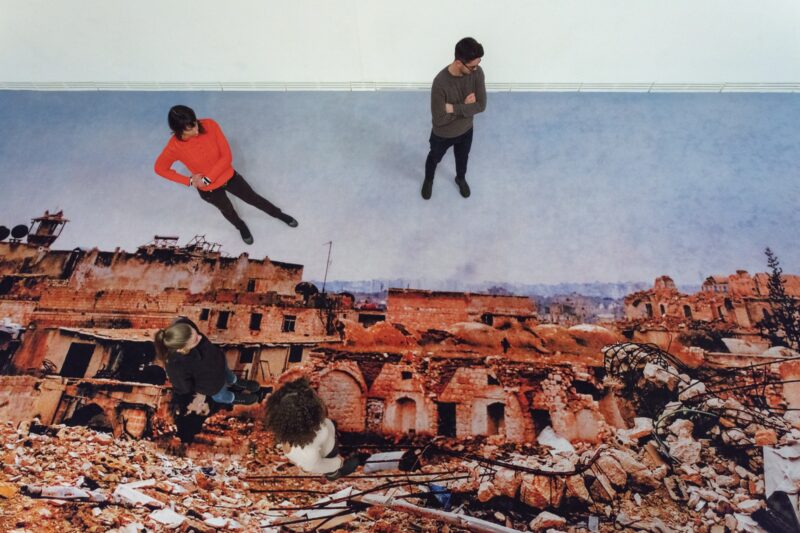

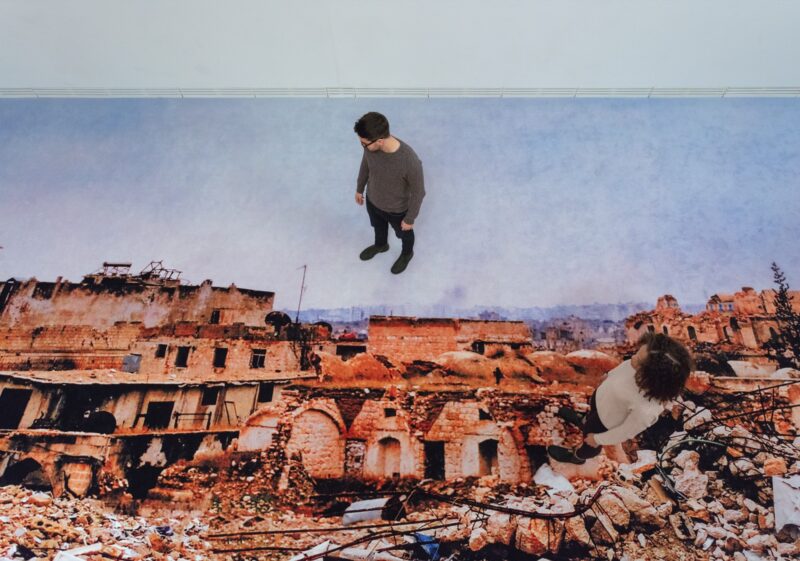

GA: I have often made works of architectural scale to place viewers in a context in which they are confronted by the physical manifestation of social or political circumstances. The gallery where my piece was located is an open, two-storey-high space. It has entrances at ground level, and there is also a balcony that overlooks it from above. I was immediately drawn to incorporating the view from the balcony down into the space below and using the expansive floor of the gallery rather than its high walls for the image. The two points of view set up by the space created multiple perspectives, literally and figuratively. When you walked into the gallery at ground level you were immersed in a massive image that is blurry with only a vague topography that is perceived in the mid-distance. From above the image is sharp – resembling a large landscape painting or panorama. The installation was like a stage set in which both those walking below and on the image are like players or actors who become complicit in the destruction.

I was particularly interested in using carpet for the image. Standing on carpet and contemplating a scene is very different from looking at a large-format photograph on the wall. It is less fleeting and sensational. When you walk on it, the image is experienced bodily. You are slowed down and have to take time to figure out what you are seeing and what you understand and think about it.

JD: What about the use of photography in your work? Was this a first-time initiative, or has photography been present in previous works, perhaps in a less obvious way?

GA: Photography has actually been an important part of my work. I have often redrawn existing photographs in order to use them in new contexts and relationships. I am especially interested in the shifts of meaning and emphasis when these images equivocate between drawing and photography. A related process is an important part of Aleppo – printing a photograph on carpet rather than on paper completely changes a viewer’s relationship with the image. I have also used appropriated photographic images in several large in situ works, combining them with material elements – most often flock – where, again, they are recontextualized to create new or different perspectives of the original image.

JD: Your entire body of work is rooted in a questioning of the decorative and its relations to power structures and inequalities. Your use of a carpet, here in Aleppo, directly calls for a questioning of the use of applied arts for the shaping of our living environments. Would you tell us a bit more about that focus on the decorative? Perhaps also about the process for producing this imposing wall-to-wall carpet?

GA: The so-called decorative arts have a materiality that I am very drawn to. There is a certain kind of power in working with forms such as wallpaper, embroidery, and hobby art or, in this case, carpet. These materials are associated with the domestic and can appear strange or out of place in certain art contexts, encouraging people to reflect on subjects in different ways. In past work, I have used flock directly on the walls of buildings to create expansive surfaces of rich velvety patterns, texts, or forms. In making these works as beautiful as possible, I have been intent on questioning a hierarchy of taste and how some things are more valued than others.

Although woven carpets are highly valued in Syria, the carpet in Aleppo was intended to relate less to Syrian than to Western culture. Despite the high quality of the process by which it was made, it is evident that the carpet has been industrially produced rather than woven. The fabric is polyester, and the scale of the image and quality of the dye-injected image is achievable only through a highly commercialized printing process.

Building the image for the final digital file was a huge and very challenging undertaking. The format of the image first had to be altered to fit the dimensional proportions of the gallery. The original found image was relatively small. To work it up to a size necessary to maintain an acceptable level of resolution at this scale was an incredibly complicated technical process. Also, despite its dramatic subject, the original was quite flat and low key. This worked as a news photograph but wouldn’t for how I was using it. A lot of adjustments had to be made, especially to the tone and colour of the image. At the same time, the actual printing was something of a roll of the dice. I worked with a company that is known for the quality of its work with this technology, but you couldn’t be there for the printing. Fortunately, the finished piece was spot on to a small proof that had been done beforehand. If it hadn’t been, the piece would not have worked.

You never know what a work will reveal. I don’t think I realized the force Aleppo would have until I walked on the carpet in the space and saw others in the work. In the end, I think the piece was not so much about the distant war in Syria and its victims as it was about us, the viewers as witnesses.

2 Michael Kimmelman, “Heartbreaking Images From Syria, So Numbingly Familiar,” New York Times, March 4, 2018, Section A, 15.

Gisele Amantea est une artiste en arts visuels connue pour son approche interdisciplinaire et son utilisation novatrice de différents matériaux, formats et procédés. Souvent réalisées in situ et de grand format, ses oeuvres explorent les questions liées au genre, à la classe, à la nostalgie, à l’histoire, au souvenir et à la relation entre espaces privé et public. Anciennement professeure agrégée au département Studio Arts de l’Université Concordia à Montréal, où elle a enseigné de 1995 à 2012, elle a présenté son travail au Canada et à l’étranger, notamment dans le cadre de Oh, Canada au MASS MoCA, à North Adams, au Massachusetts, en 2012, exposition majeure consacrée à l’art contemporain canadien.

www.giseleamantea.ca