[Winter 2020]

Par Alexis Desgagnés

On the threshold of my teenage years, my greatest passion was to observe birds. I spent countless hours, binoculars hung around my neck, prowling slowly, silently, through woods and meadows, looking out for a rare gem! When I was thirteen, a camera, a gift from my stepmother, replaced the binoculars, gradually turning my destiny from ornithology toward art. I still remember how surprised I was at my first photographs – of birds, of course. Photographed with a 50 mm lens, the birds in these pictures were simply indistinct points in vast landscapes. Quickly, my disappointment in these pathetic images gave way to a question, which seems today to have been the origin of my reflections on art: how does one photograph birds?

Implicitly underlying this seemingly simple quandary, which I attempted to solve by obvious technical means (refining the approach to the subject, using a telephoto lens), was intuitively inscribed a fundamental questions of principle, which spoke to me about the close relationship between ornithology and photography. What does it mean to observe? How is the subjectivity of the one who observes tied to the objectivity of the one who is observed? What is the gaze? What is a point of view? Years later, I found echoes of these preoccupations in books by English photographer Stephen Gill, especially in The Pillar, which received the Author Book Award at Les Rencontres d’Arles 2019.

Career of an Experimenter. Since the late 1990s, Gill has stood out as one of the most original photographers of his generation. An eclectic artist with projects irreducible to a single unambiguous aesthetic, he is a daring experimenter whose approach refers to the registers of both the human sciences (anthropology, archaeology) and the natural sciences (biology, ethology, ecology). It is also difficult to dissociate his imagery from his relationship with the medium of the book, which is the principal catalyst for his series. In order to keep full control over the editorial process leading to publication of his books, Gill founded the publishing house Nobody Books in 2005.1

Gill’s approach can be seen, above all, as being in the spirit of field studies. In a number of interviews published on the Internet, he qualifies his photography as descriptive. Apparently, he wishes to record the places he explores during his wanderings in a relatively detached manner. Although this stance brings him into contact with the documentary tradition, we must nevertheless acknowledge the conceptual dimension of many of his series, due either to their subject or to how the images composing them are produced.

Having undertaken anthropological documentary work early in his career,2 in 2003 Gill devoted several projects to the East London working-class neighbourhood of Hackney Wick (Hackney Wick, 2005; Warming Down, 2008). The images show both the area’s population of immigrants and refugees and its desolate urban landscapes. The photographs were made with a cheap camera acquired for a few dollars at a local flea market. Photographing Hackney Wick in this way enabled Gill to undertake a sort of “archaeology in reverse,” as the title of one of his photographs makes explicit (Archeology in Reverse, 2007), at a time when the neighbourhood was about to be undergo major transformations due to the construction of infrastructure for the 2012 Olympic Games.

But again, this London body of work gave Gill an opportunity to expand his experimentation in an approach in which he multiplied strategies for extending the frontiers of photographic language. He buried prints in the Hackney ground so that soil and rain would degrade their emulsion (Buried, 2006); he rephotographed prints and placed on their surface various plant matter and other objects found where he had taken the pictures (Hackney Flowers, 2007); he introduced certain items into the body of the camera to generate what he called “in-camera photograms” (Talking to Ants, 2014); he developed film using energy drinks (Best Before End, 2014).

For some of his projects, Gill turned to completely different approaches, such as appropriation (Unseen UK, 2006; Hackney Kisses, 2014). Some of his books present objects found in different contexts, such as stones and other projectiles used during the 2001 London riots (Off Ground, 2011) and bits of toilet paper found in hotels that he visited around the world (Anonymous Origami, 2007). His production, thus, is not tied exclusively to London. He has produced series in Brighton (Outside In, 2010), Japan (Coming Up for Air and B Sides, 2010), Trinidad (Trinidad 44 Photographs, 2009), Luxembourg (Coexistence, 2011), and Sweden (Night Procession, 2017, and The Pillar, 2019), where he now lives with his family.

Portrait of the Artist as Naturalist: Coexistence and Night Procession. There arises from many of the works described above, but also from other, more recent bodies of work, an impression of great proximity between Gill’s artistic approach and that of a naturalist, a lover of natural sciences. This aspect of Gill’s work, still indirect when he was using plant matter and insects to enrich his photographic language, became fully clarified in 2011, when he put out the book Coexistence, one of his most ambitious publishing projects.

Coexistence is the result of a commission given to Gill by the Centre national de l’audiovisuel in Luxembourg.3 As it involved an in situ project, Gill took an interest in the ponds at the water tower in Dudelange, on the site of a steel plant that had been in operation from 1883 to 2005. When he discovered this disused land reminiscent of the fields that had inspired him as a teenager, when he would spend hours observing life in a pond, Gill chose to highlight in his book the interrelationship between the microscopic world of stagnant pond water and the macroscopic world of residents of Dudelange.

Published in the form of a sumptuous large photobook with a print run of 1,500 copies,4 Coexistence contains mainly photographs that Gill took with a medical microscope on loan from the University of Luxembourg, which he used to examine water drawn from the pools of the industrial site. The series comprises photographs showing the site itself as well as portraits of residents of Dudelange. The heterogeneous nature of this body of work is attenuated considerably by the particular look of the images, which is the result of an experimental procedure – faithful in this sense to Gill’s approach – in which he dipped his prints in water from the ponds in order to give them a soiled, watery look.

In 2017, Gill published the book Night Procession, in which he once again followed in the footsteps of the naturalist. Night Procession is composed of photographs taken in the Swedish countryside that expose the nocturnal activities of wild animals. Leaving behind motion detectors and an infrared flash, Gill slipped out of the woods to leave free rein to the night-time fauna, delegating observation to his camera. On page after page, foxes, deer, reindeer, vultures, slugs, field mice, beavers, moose, hares, wolves, warblers, and boars serenely file through the dense forest, at the foot of trees or by watering holes. The poetic intensity of this nocturnal procession, captured with documentary veracity, only makes more obvious the absence of the photographer. A few childlike faces inserted here and there throughout the book suggest the point to which nature is our primordial family.

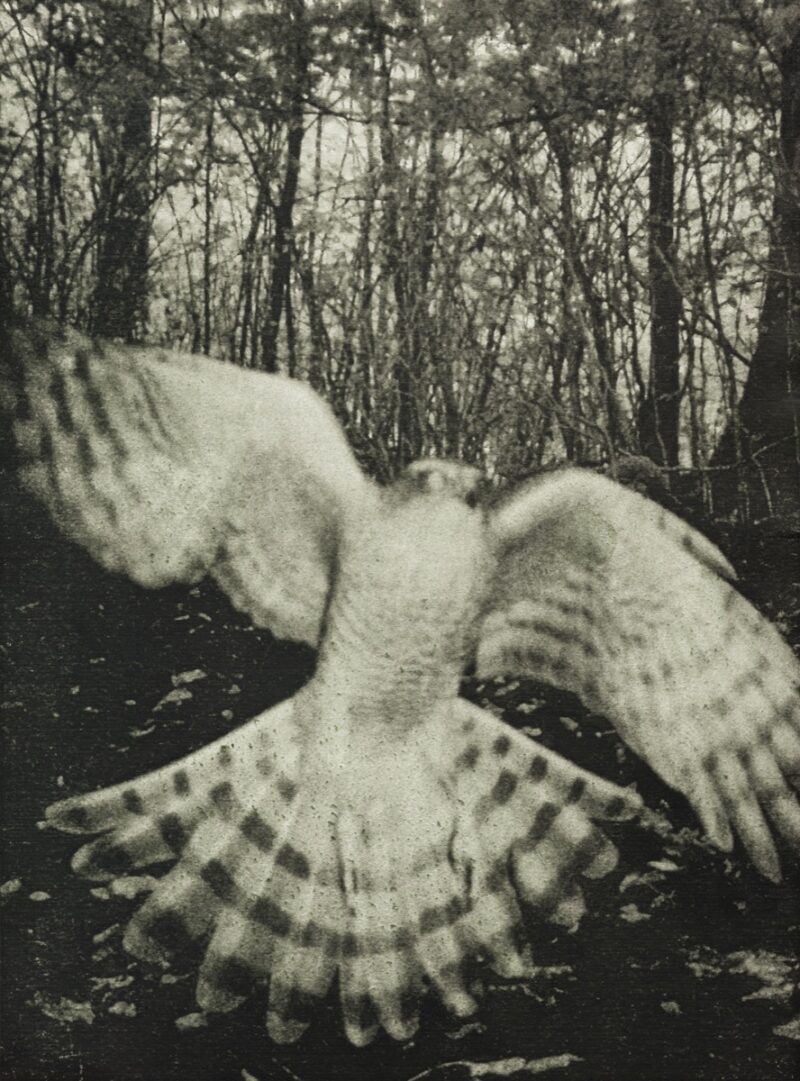

Of Books and Birds. On the flip side from Gill’s wandering approach in London, for The Pillar (2019), he once again takes advantage of the possibilities of automated photography, this time to serve ornithology. An automated camera is installed in front of a pole – or, rather, a pillar, if we take the book’s title at face value – that becomes a perch. Season after season, it is visited by avian fauna in a Swedish landscape. In the distance, the horizon is dotted by farms.

The code of ethics followed by most ornithologists starts with the following precept: one must avoid disturbing birds as one observes them. We see in this book the extent to which Gill goes to keep a low profile, even though, in the 2014 series Pigeons, he portrayed pigeons in a unique way, assaulting them with a violent flash that was direct, intrusive, in the style of a Bruce Gilden. What Gill’s pigeons showed us was “how life is rooted in the theatre of its deployment, edified, against history, from bare steel, guano, and the accumulation of days.”5 In The Pillar, Gill, this time more ornithologist than photographer, simply lets life be, without theatre or set, in its agricultural, rural, seasonal habitat and landscape.

We recognize here something of the approach that Gill took in A Book of Birds (2010), a book that I might have been able to produce if, at the dawn of my adolescence, I too had been a good artist. Again according to the ornithologist’s code of ethics, the identification of a bird presumes the observation of its habitat. In A Book of Birds, without disappointment, the birds are simply indistinct points in vast landscapes. A sparrow, a pigeon, a heron, or any other bird that we might see in a city, in an urban, built environment. A mourning dove. “I wanted to make a study of how birds fit and mould their lives around ours and adapt to what we have created,” Gill writes on the web page for A Book of Birds. “I was also very interested to hear that scientists found that birds in towns and cities sing louder or use higher frequencies compared to the same rural species so they can be heard above the man-made noise.”6 Gill, as much a naturalist here as in The Pillar, Night Procession, and Coexistence, makes clear the extent to which fauna doesn’t cohabit with human forces; it adapts, it transfers itself to the poverty of human landscapes – urban, degraded, stripped of all wild nature. Acclimatized, domesticated, acculturated, civilized fauna.

In The Pillar, it’s all about the question of the point of view – static, immobile, silent, attentive, contemplative – that underlies the motif of the pillar. The question of observation. Of a code of ethics, in both ornithology and photography. What relationship ties the subjectivity of the one who observes to the objectivity of the one who is observed? What is the gaze?

An ecosystem. A mourning dove.

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 Portraits of individuals wearing headphones, passengers on trains, lost tourists, and ordinary people with shopping carts; photographs of ATMs, construction sites, and billboards. These series were brought together in the book Field Studies (London: Chris Boot, 2004).

3 Stephen Gill, Coexistence (London and Luxembourg: Nobody Books and Centre national de l’audiovisuel, 2012). See also http://cna.public.lu/fr/actualites/photographie/2012/09/gill/index.html.

4 Six variants of the book were put into circulation, each with a print run of 250 copies. The only difference between the variants was the cover, printed on a different marbled paper for each print run.

5 Alexis Desgagnés, “Habitat,” trans. Käthe Roth, Ciel variable 99 (January–May 2015): 11. See also, in the same issue, the portfolio devoted to Gill on pp. 12–21.

6 https://www.nobodybooks.com/product/a-book-of-birds.

Artist and author Alexis Desgagnés lives in Montreal. He teaches art his tory at the college level and is an activist in a union. His poem “Ornithologie” will be published in a collection of poems and photographs titled Métamorphose, coauthored with Serge Clément.