[Hiver 2020]

Galerie La Castiglione

May 15–June 15, 2019

By Stéphanie Hornstein

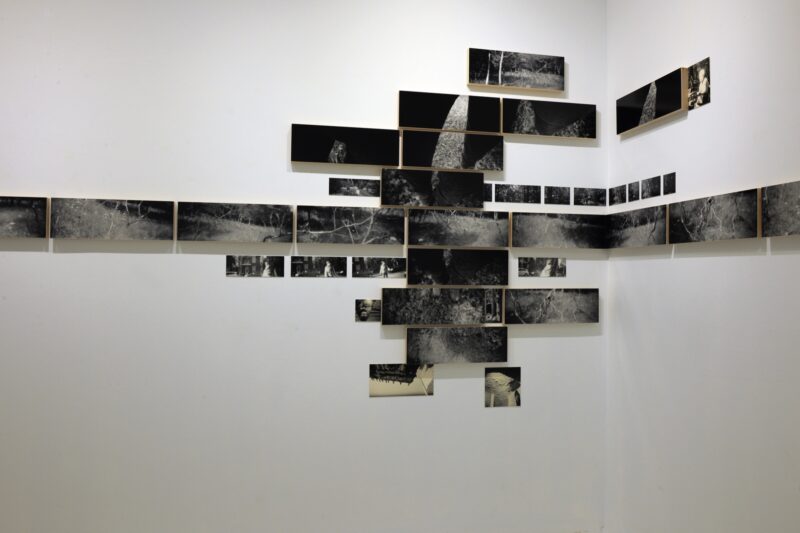

The day that I first make it to Yan Giguère’s solo show at Galerie La Castiglione, Montreal’s construction season is in full swing. St. Catherine Street is a gaping trench and the jackhammer’s thrum hounds me all the way up four flights of stairs. But inside the gallery, where Giguère’s photographic groupings constellate across the walls, the tranquil composure of another world greets me. A large frieze of swaying grass pulls and holds my attention. True to their landscape subject, the twenty-four pictures that make up Les herbes were taken horizontally, but they are displayed flipped on their sides, recalling the planks of a wooden fence. Installed across a corner of the room, the work wraps me in a kind of pleasant hypnosis, banishing all memories of unsightly orange cones from my consciousness. Sightlines converge. The grainy texture of the prints adds something of a reverie to the experience, and I soon find myself lulled by the stilled movement of the blades of grass that appear like so many brushstrokes against a hazy sky.

The series presented in Suite cinétique are the fruits of Giguère’s five years of experiments with a LomoKino Movie Maker—a palm-sized camera that boasts, according to its manufacturer, a “gloriously analogue” aesthetic. Loaded with standard 35mm film, the device allows users to capture several frames in rapid succession by operating a small crank. The LomoKino has no adjustable focus or shutter speed, but Giguère is no stranger to low-fi equipment. Quite the opposite: much of his practice proceeds from a love affair with the gimmicky cameras developed for the consumer market. Over the course of his considerable career, he has toyed with everything from the Kodak Instamatic to the Soviet-era Shkolnik and pseudotechy turn-of-the-millennium gadgets such as the four-lens Action Sampler. It is the quirkiness of these nonprofessional cameras that, in Giguère’s words, gives each photograph a signature. The LomoKino, for instance, produces images in slim strips with a 2.8:1 aspect ratio that makes them too narrow to be conventionally cinematic. They are, however, brimming with experimental potential. What subjects can adequately be pictured within such tight proportions – a tree line, a pair of eyes, the horizon? What unusual cropping or panoramic vistas are made possible? This is what Giguère seems bent on exploring.

In the elaborate assemblages on display at La Castiglione, movement is arrested but never reanimated in the kind of short motion pictures for which the LomoKino was conceived. Instead, Giguère has made enlargements from individual negatives and, in the style of previous projects, has juxtaposed them with other photographs pulled from his vast portfolio – a portfolio that consists, rather bravely, of the everyday records of his own life. “My work space is an absolute mess,” he replies when I ask him how he concocts his arrangements. “It partially depends on what images end up on the table together.” Describing his projects as “indeterminate tomato plants,” he combines photographs intuitively, allowing connections to unfold and temporalities to collide.

In Entrelacs, for example, different seasons coexist: a stick frozen in ice neighbours a sun-drenched path; a bumblebee makes its way to the centre of a bloom while, in several other frames, bare branches scrape the sky. Polaroid pops of colour perch atop silvery prints. Two construction cranes call to each other from opposite ends of this aggregation, the gravitational centre of which is the profile of a woman who bows her head while trees blur around her. She is, of course, Marie-Claude Bouthillier, celebrated Montreal painter and Giguère’s partner, whose presence is a constant in his oeuvre. Curator Marie-Claude Landry has suggested that because Giguère’s compositions are “rooted in an intimacy that is not ours,” they encourage the kind of speculation that a stranger’s family album might. This is possibly why the figure of Bouthillier is such a comforting one to latch onto.

We find her again in Nous trois, an unassuming yet moving three-way portrait. Read sequentially from top to bottom, the first four photographs register the infinitesimal changes that occur in Bouthillier’s expression over the few seconds during which they were captured. She cocks her head to the side, inquisitive, as if wondering what game she is being asked to participate in now. The muse may be wearier here than when we spot her relaxing in L’éclaircie, but she clearly still humours her documentalist. In the final strip, Giguère’s own face, all smiles, makes an abrupt cameo appearance, marking the only moment in the exhibition when the tireless compiler reveals himself so directly. Crouching behind him on the bed is the third party implied by the artwork’s title: a disgruntled cat.

This simple ode to everyday togetherness might not have the sprawling mass of Giguère’s better-known photo mosaics, but it distils the substance of his work. His concern with the malleable poetry of time is palpable in this piece, as is his knack for finding the marvellous in the mundane. Considered alongside the other projects in Suite cinétique, these five stills speak to the painstaking selection process that he constantly enacts on a personal archive, the enormity of which we feel though we do not see it. Perhaps it is in this way, and not solely in his use of the LomoKino, that his approach most resembles that of a filmmaker who, sitting at the editing console, splices and reassembles, discarding outtakes from the final cut. But his are not linear stories; they keep us searching. What is clear, however, is that his not-quite-narratives have a strangely compelling power to them, even if their logic remains elusive.

Stéphanie Hornstein is a PhD candidate in art history at Concordia University, where she researches patterns in nineteenth and earlytwentiethcentury travel photographs. Her writing can be found in History of Photography, RACAR, and Counterpoint Magazine.