[Summer 2020]

By Érika Nimis

Interdisciplinary artist William Kentridge (born 1955 in Johannesburg) is internationally celebrated for his animated films composed of charcoal drawings and as a director of live shows. Born into an activist family intimately involved with the anti-apartheid struggles of the 1980s, Kentridge works in media as varied as printmaking, sculpture, performance, theatre, and opera. In 2016, the National Gallery of Canada acquired his immersive video installation More Sweetly Play the Dance (2015). Following its presentation at the Art Gallery of Alberta, it has been in Ottawa since December 2019,1 alongside another, older work also acquired by the Gallery, What Will Come (2007).2

More Sweetly Play the Dance is installed in a space defined by a circle of eight large screens onto which are projected changing landscapes drawn in charcoal, representing the areas surrounding Johannesburg that have been destroyed by intensive mining. In the centre of the room are chairs of various shapes and sizes and four speakers whose shadows are projected onto the screens. Spectators can place themselves anywhere and move the chairs to “join the dance.” In other words, the spectators are part of the work, and their interaction with it conditions their reception of it.

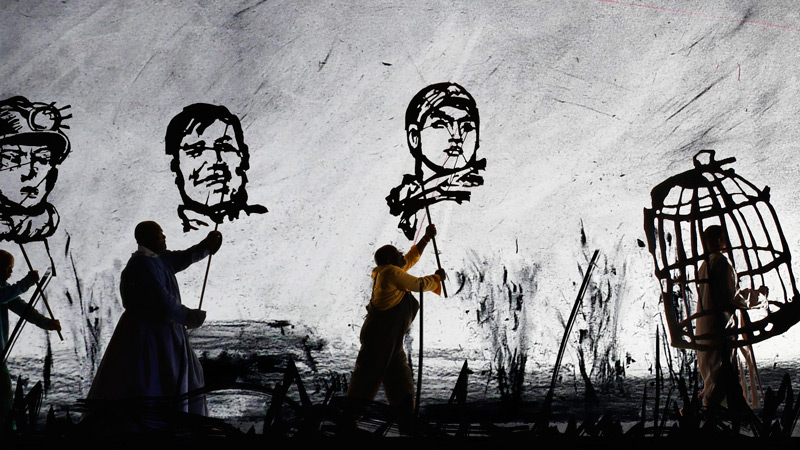

The soundtrack starts. A man spinning to the rhythm of the percussion crosses the eight screens from right to left in a single movement and then disappears. Another man enters from the left, walking slowly, holding himself as straight as an arrow, scattering sheets of paper behind him with broad, nonchalant gestures, closely followed by a heavy-stepping, forward-leaning flag bearer, who eventually passes him. On the flag carried by this revolutionary figure, we glimpse glued strips of paper with covered with slogans. Then, a few notes burst forth to announce the entrance of a marching brass band: it leads the dance, both literally and figuratively. Kentridge collaborated with the African Immanuel Essemblies Brass Band, which is performing its piece specially written for the work. As the band plays, a procession of motley characters files by in a shadow play. The silhouettes, partly real (filmed) and partly drawn – at the intersection of video and animation – are projected life size, evoking a sense of wonder like that we might feel watching a magic lantern show. But when we look more closely, this strange procession, or perhaps it’s a parade of the dead, is not enchanting at all. Rather, it resembles a contemporary danse macabre, including a random collection of priests bearing branches and imaginary birds, men carrying cages in which they are trapped, and people holding up on poles the effigies of saints, heroic figures, and random objects (all of these drawn in animation). Interspersed with them are a cart of “spokesmen” and another one carrying politicians at their lecterns along with the stenographers who transcribe their speeches; miners, ragpickers, people from all social strata; and groups of professional weepers, patients rolling their medication drips, people dragging a gallows from which hang drawn cut-out paper skeletons. A ballet dancer on a cart, wearing a red beret and gracefully handling a rifle, closes the march. Each character “performs” the procession at his or her pace, guided by his or her own reflexes, but all are going in the same direction. Where? It’s hard to know.

The reference to the repressive context of apartheid is explicit, however: at one time, funeral processions were the only means through which blacks could defy the ban against their meeting in public and thus offered the only opportunity for them to express their rejection of the system. As Kentridge states, “The procession is a form I have used many times before, trying to encompass in the work the muchness of people in the world. And to record the fact that here in the twenty-first century, human foot power is still the primary means of locomotion and we are still locked in the manual labor or individual bodies as a way of making the world. Specifically the image of a procession goes back to Goya and his paintings of processions.”3

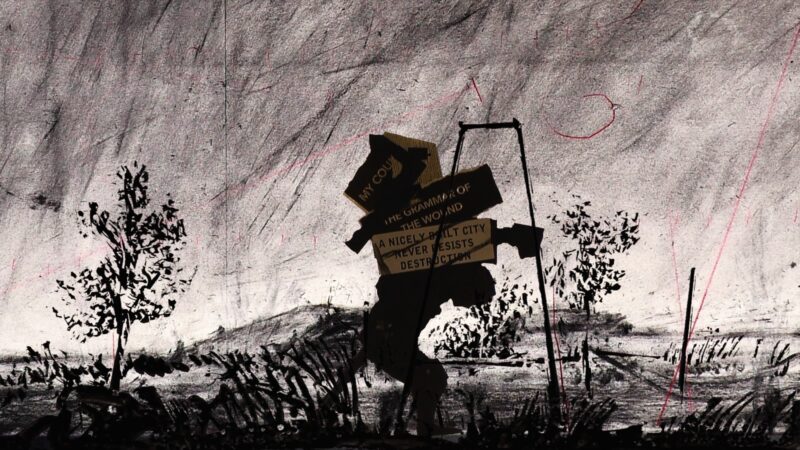

Painter and printmaker Francisco de Goya’s The Disasters of War (1810–15) is one of the many references feeding into More Sweetly Play the Dance. The title is inspired by Paul Celan’s poem Todesfuge (Fugue of Death) (1948) about the Second World War and the Holocaust.4 The heroic figures brandished in effigy by the marchers refer to Roman antiquity, including Cicero and his mentor, Quintus Mucius Scaevola; defenders of civil justice; and the European Renaissance, with philosopher Giordano Bruno, freedom-of-expression icon. The slogans glued to the flag carried by the “revolutionary” at the beginning of the procession are chilling, however: “the unhealthy inscription” and “bombard the headquarters,” title of a short speech by Mao Zedong, dated August 5, 1966, which provoked the death of thousands of people. These are specific references to communism (inseparable from the history of the anti-apartheid struggle) and its totalitarian misconduct in the context of the cold war. We also see, at the end of the procession, a character waving a large red flag.

Although Kentridge clearly draws his references from the tragic course of history, he does so in order to better explore the march of the world. In the codes of historical painting, a march goes from left to right. But in Kentridge’s installation, the direction of the march is looped – or circular. In this vast fresco in motion, the different figures in the procession stand for the many layers of a single narrative that questions the direction of history – or, rather, its lack of direction. About his activism, Kentridge has said, “I have never tried to make illustrations of Apartheid, but the drawings and films are certainly spawned by and feed off the brutalized society left in its wake. I am interested in a political art, that is to say an art of ambiguity, contradiction, uncompleted gestures, and uncertain endings – an art (and a politics) in which optimism is kept in check, and nihilism at bay.”5

In the end, this work, open to multiple interpretations, suggests more than it dictates. Kentridge creates paths, drawing on his own references – paths that he constantly blurs to reject all certainty, which he considers dangerous. In its place, he summons the performing arts, especially music and dance, through collaborations with other South African artists. In addition to the African Immanuel Essemblies Brass Band, which lent its energy to this work, Kentridge collaborated with choreographer Dada Masilo. Masilo’s style is recognizable in the different dances performed by characters in the procession, notably the original stick-and-shovel dances, traditionally performed by Johannesburg miners, that bring a local touch to this work of many pieces with no temporal or spatial boundaries. The soundtrack also offers a few exhilarating surprises, such as when the brass band interrupts its piece to attack the well-known tune “Aquarela do Brasil” (known simply as “Brazil” in English) made famous in Terry Gillam’s cult film Brazil (1985), a fierce and hopeless critique of totalitarianism in all its forms. Translated by Käthe Roth

1 More Sweetly Play the Dance, 2015, video installation presented at the National Gallery of Canada from December 14, 2019, to November 8, 2020.

2 What Will Come (2007) is an anamorphic animated film evoking the invasion of Abyssinia by Mussolini’s troops in 1935–36, ultimately vanquishing the Ethiopian army through the use of chemical weapons.

3 William Kentridge, quoted in William Kentridge: More Sweetly Play the Dance (Amsterdam: EYE Filmmuseum, 2015), 25.

4 The connections between apartheid and the traumas of the Second World War have been explored by other South African artists, including photographer Santu Mofokeng (1956–2020), who, in the series Trauma Landscapesand Landscape and Memory, explores history through the landscapes of his own country in dialogue with those of Auschwitz, Ravensbrück, and Hiroshima.

5 William Kentridge quoted in Michael Godby, “William Kentridge: Retrospective,” Art Journal 58, no. 3 (Autumn 1999): 83.

Érika Nimis is a photographer, historian of Africa, and associate professor in the Art History Department at the Université du Québec à Montréal. She is the author of three books on the history of photography in West Africa, including one adapted from the doctoral dissertation, Photographes d’Afrique de l’Ouest. L’expérience yoruba (Paris: Karthala, 2005). She contributes to various magazines and founded, with Marian Nur Goni, a blog devoted to photography in Africa: fotota.hypotheses.org/.

William Kentridge, the son of white South African anti-apartheid lawyers, has been creating highly humanistic works for the last thirty years. His installations, drawings, films, and theatre projects are known for their poetic strength and critical discourse. Internationally celebrated, he has been invited to have exhibitions in museums and biennales around the world, and his works are in numerous public and private collections. www.mariangoodman.com/artists/49-william-kentridge/