[Winter 2021]

Par Yannick Marcoux

Looking back upon our origins, it was a long time ago – a very long time, ten thousand years in fact – that the last ice age ended on Earth. What remains of that epoch seems to fascinate Alain Lefort, who, after making his series Eidolôn on drifting icebergs, has slipped back into his parka and returned to the lily-white lands of winter for a new series.

Presented for the first time at the Maison de la culture du Plateau-Mont-Royal, the exhibition Résonance des silences – a title evoking collisions of ice with roiling waters and their dull echo in the tundra plains – creates a discursive loop of eight works. The works follow three approaches: landscape, video, and photomontage or, more precisely, the deconstruction of a landscape photographed from a number of angles.

This new series, an invitation to contemplate stunningly beautiful landscapes, is made of a number of ruptures that create sudden distancings, breaking the spell that it casts. Lefort is seeking to rouse our awareness of the artworks and, incidentally, to challenge our presence in the world. As a reflection on origins – both those of the image itself and the broader ones of our habitat – the exhibition proceeds on a theme that runs through each piece: water. So, let’s dive in.

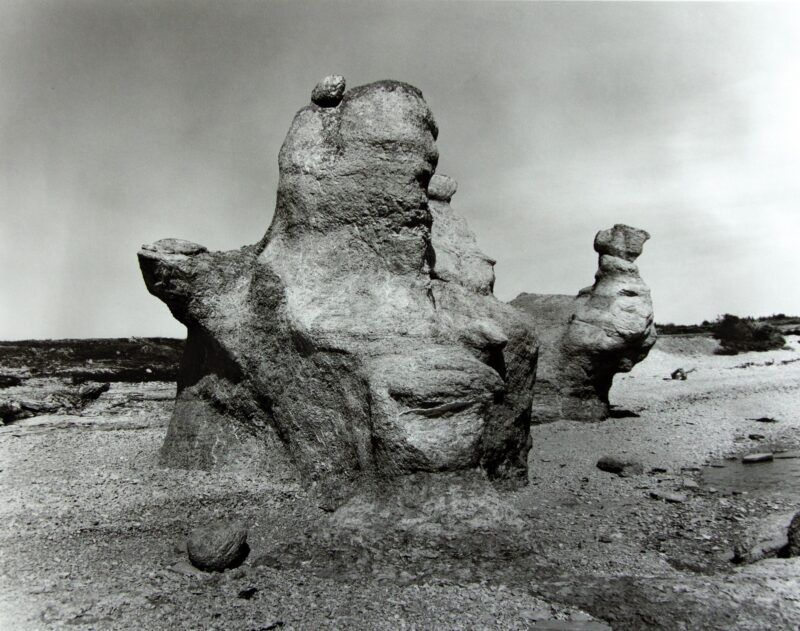

Monolithe 1 and Lac-Saint-Louis. The first work is a black-and-white silver print of one of the monoliths that Archipel-de-Mingan is famous for. A natural phenomenon, the immense monolith has a human morphology and is an artwork in itself, posed on its limestone base and sculpted by the erosion, both mechanical and chemical, of sea water.

The depth of the projections and the rounded shapes highlight the transformations in the limestone block. Here, it is through the work of the water that Lefort stages himself, as these transformations create a suggestive force, the representation of something else. In short, an artwork. Even in black and white, Lefort flies his colours: it is important to him to leave a trace of the creative gesture.

New traces – or imprints – permeate the next photograph, which shows a lake made turbulent by slabs of ice and from which thick condensation rises; the sky, in the background, seems like a mirage. Lefort is again a privileged witness, carefully keeping vigil over a landscape spread before him. This time, however, his traces are inscribed in the materiality of the print: the cold burned the negative, whitening the edges and creating ethereal contours in the landscape, like a pale reflection of the blazing sun in the centre, which gives the impression that the photograph has begun to catch fire.

These first two works differ, aesthetically and materially, from the rest of the series. They can be considered for what they are – landscapes capturing a beauty offered to the eye – but Lefort transcends this basic function and uses these images to establish the conditions for reading his series. It is not enough to admire beauty from afar; one must enter it, retrace the creative process, and survey the materiality of the work, recognizing that everything is transformation.

De/construction. In his subsequent photographs, Lefort takes us to distant, difficult-to-access Ivujiviup, where the landscapes are both unexpected and incredible. This time, he features vast stretches of frozen water where the impact of the ice has created blocks and peaks, resembling stalagmites, evoking the spectacular repetitions of the Terracotta Army. In the distance, apparently unreachable, uninhabited islands

of snow-covered stone – the Digges Islands, the natural line beyond which the Arctic begins – stand out.

Here, Lefort’s discursive mechanics create relief features. Rather than succumb to the beauty of the landscapes, he constructs it. In a practice recurrent in his work – notably, the series Black Mangrove Forest – the territory has been fragmented in the pictures taken and reconstructed in the studio, a technique that Sylvain Campeau, in his essay “Landscape, Raw and Immeasurable,” has described as “a reduplication, a web of numerous images stitched together.” These landscapes are composed of a number of superimposed photographs, creating visual ruptures that accentuate light contrasts and amplify the effect of immensity, while betraying our reflexive reading. For instance, the horizon of Agiaq-Qikirtaaruk is presented in a vertical logic. These works induce the genesis of their creation, allowing visible traces of the photographer’s work to upset the apparent objectivity of the photograph.

In this way, Lefort appropriates the subject and choosesto inscribe himself in it. By multiplying points of view, he even invites us in, as if each different angle corresponded to each of our gazes. It is a tour de force: Lefort takes us with him into these improbable lands of the North.

The short Ivujiviup series also implies a sense of moving forward, as the craggy headlands, distant and unapproachable in Qikirtaaruk, are close by in Akia, as if the territory had been apprehended, surveyed, almost conquered. By evoking our symbolic presence in this way, Lefort forces us to consider a painful question: what impact do the simple facts and gestures of our lives have on places that we thought were untouchable and unaltered?

As if the answer should summon up the necessary humility, Lefort ends the Ivujiviup series with Kangituuq, which returns to nature all its power and sovereignty. Sky and snow flatten the relief features, leaving a surging white that saturates the image, in the centre of which an arch opens – perhaps

to Plato’s forgotten cave; the territory swallows us up and ascends to its rightful dominance over humanity. Lefort’s intervention is minimal here, as if he has been subdued by the landscape or has adopted a more remote and admiring position, creating a loop in the exhibition.

Pixels 1 and 2. At the heart of this short series on Ivujiviup are two videos. The first captures the Brillant Rapids and skilfully plays on the opposition between movement and stagnation. In the cat-and-mouse game between the camera and the wave’s motion, it is sometimes hard to figure out which is chasing the other. Lefort burrows into the wave, zooming in to the image until there is only one pixel in his lens. The origin of the image. It’s also what is presented in the following video: an isolated pixel.

After constructing landscapes and leaving traces of his work, Lefort climbs back down the thread of the images to its smallest denominator: the pixel. This desire to return to the essence, to the origin, still pure and unviolated, creates a mise en abyme in the narrative of the series. The elusive pixel is the northern territory, majestic and fragile, the essence of which Lefort is trying to capture, but to which he must add new pixels, new images, to be able to share it with us.

Résonance des silences offers an elegy to our habitat that, at first a contemplative and neutral work, gradually grounds its subjectivity. These landscapes, both magnificent and hostile to human life, are unsettled, symbolically, by Lefort. His work examines the impact of our presence in territories that are seemingly unattainable and unaltered and yet are jeopardized, from afar, by human activity. More than a memory, these photographs are an awakened awareness, a reminder that the survival – or death – of beauty is up to us. Translated by Käthe Roth

1 Sylvain Campeau, “Landscape, Raw and Immeasurable,” in Sylvain Campeau and James D. Campbell, Alain Lefort (Longueuil: Plein sud, 2016), 38.

Yannick Marcoux is a literary critic for the Montreal daily Le Devoir and contributes to magazines, blogs, and literary magazines as a prose writer, poet, and columnist. Twice a finalist for the Prix de la création de Radio-Canada (in the story and poetry sections) and the most recent recipient of the Prix littéraire Pauline-Gill de la nouvelle, he has also written several plays.