Exposing alterity. Curator Jaime González Solis has deployed the exhibition in two sections. The first is devoted to the way of life inherent to the Yanomami worldview; the second delves into the struggle for survival that they have led for almost fifty years. In each section, the photographs are grouped under themes such as “The Forest of Life,” “The Privacy of the Home,” “Rights and Vision,” “Vaccination and Health,” and “Genocide of the Yanomami: The Death of Brazil 1989/2018.” The hundreds of photographs on display, many of which have never been shown before, come from Andujar’s archives. Most of these images, in black and white or coloured with filters, are silver prints taken between 1971 and 1977, when Andujar regularly visited the Catrimani River region. Many are affixed to the walls; other are hanging back to back in the various exhibition spaces.

To provide a perceptive portrait of various aspects of Yanomami life, Andujar experimented not only with colour filters but with infrared – high-sensitivity – film. She sometimes applied Vaseline to the lens and used flashes or oil lamps, as well as superimposition,

depending on the desired effect. In the first gallery, a photograph shows the face of a teenage girl, her head just out of the water, the skin around her lips pierced with thin rods as a facial ornament. This peaceful visage, emerging from the indigo-blue water, contrasts with the peril of a coming genocide. Beside it, a photograph of the landscape shows a cloudy sky hugging red-coloured earth. In the same gallery is an image of a collective house – a maloca – seen from a helicopter, surrounded by a fuchsia-coloured forest. These circular abodes are used for two to three years, after which the Yanomami burn them and move.

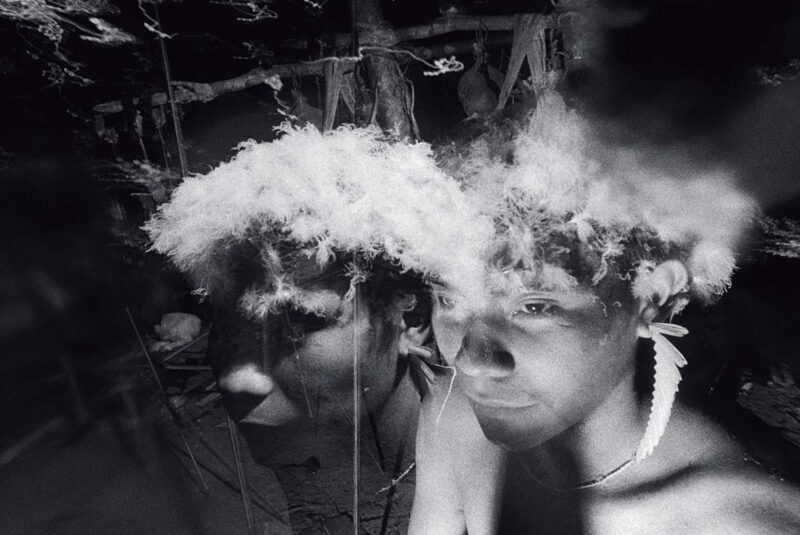

In an adjacent gallery, a large mosaic of black-and-white portraits presents close-ups of heads, as well as fragments of bodies such as bellies, breasts, and a penis held by a string at hip level. The faces reveal an enigmatic beauty. Rarely do they look at the camera; either their eyes are half-closed or they modestly turn away from the lens and gaze into the distance. Although these chiaroscuro portraits testify to Andujar’s closeness to the members of the community and a connection of undeniable trust, they also retain a sense of mystery. In the same gallery, other photographs give a different view of the innocence of this people of hunter-gatherers, for whom the forest, plants, and animals are an essential part of life. Still other images, also in black and white, show daily life in the forest. Yanomami youths – young men, body often painted with undulating lines, dozing in a hammock; young women with downy feathers laced into their hair – live simply, a world away from the pace of urban excitement.

Among these photographs taken beneath the forest canopy, one is particularly surprising. We see a boy inside a maloca. Light streams down from the roof made of palm-tree branches, and the child alone in this large shelter is surrounded by a halo that makes him look almost ghostly. The same effect of light piercing shadow can be seen in many other photographs, but here the enhaloed presence of the boy evokes xapiripë, the luminous spirits of the sky and the forest. Unlike in Western tradition, the Yanomami do not divide the world into natural and supernatural. Their vision of the world falls within a monistic ontology marked by animism, a conception that incorporates the human species within the whole of life, human and non-human. In the view of the local shaman Davi Kopenawa, coauthor with the anthropologist Bruce Albert of the book Yanomami, l’esprit de la forêt, this symbiosis with nature need not be reproduced but it must be respected, or else the survival of the planet – and especially the survival of this community – is threatened.

To offer another perspective on this world in which the material and spiritual worlds communicate, during her visits to the Yanomami Andujar handed out paper and coloured pencils to members of the community. Some of them, starting with Kopenawa, but also André Taniki, Orlando Naki uxima, and Poraco Hiko, expressed themselves by drawing a facet of their culture. Most of these illustrations are gathered together in a space devoted to them in the exhibition. Figuratively, and sometimes abstractly, they portray aspects of daily life and of beliefs shaped by cosmology. Unlike Andujar’s photographs, they offer access to the Yanomami sensibility and imaginary, notably with regard to shamanic rituals.

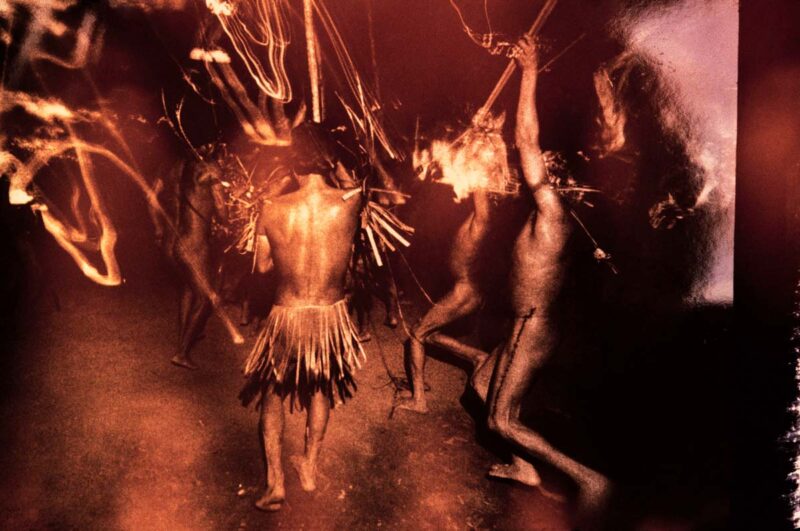

Andujar, however, captures on film only situations from life. Many photographs document gatherings around the reahu, a festival of song and dance celebrating events that bring the communities together. During these celebrations, the shamans inhale yakoana,

a psychotropic powder that is blown into the nostrils by another person using a bamboo tube. Other images present a young man who has inhaled yakoana and whose ecstatic state is suggested by vibrations of light indicating its psychedelic effects.

Andujar started off as a photojournalist, but her encounter with the Yanomami diverted her from that profession. More than bearing witness to events that might rouse public opinion through the mass media, she wanted to discover, as closely and intimately as possible, their way of life. In interviews, she notes that her role throughout her years of visits was to understand them. Yet, understanding involves engagement, transforming oneself in contact with the other. At the turn of the last century, Victor Segalen (1878–1919), in Essai sur l’exotisme: Une esthétique du divers, understood that colonial control could only weaken global cultural diversity. He deplored that travel tended to standardize ways of life and mask the teeming strangeness of difference. So, as Andujar tries to do with her camera, the act of understanding must resist assimilation – it must keep this distance alive for diversity’s sake.

Ethical engagement: Beyond photojournalism. Very early in her series of sojourns with the Yanomami, Andujar began to comprehend the fragility of life within this vast territory. In the late 1970s, with Albert and the missionary Carlo Zacquini, she set up the Comissão pela Criação do Parque Yanomami (Commission for the Creation of Yanomami Park, or CCPY), a nongovernmental organization devoted to protecting the territorial, civil, and cultural rights of the Yanomami. The second section of the exhibition is dedicated to her involvement with the struggle of this people, to whom Andujar often refers as her new family.

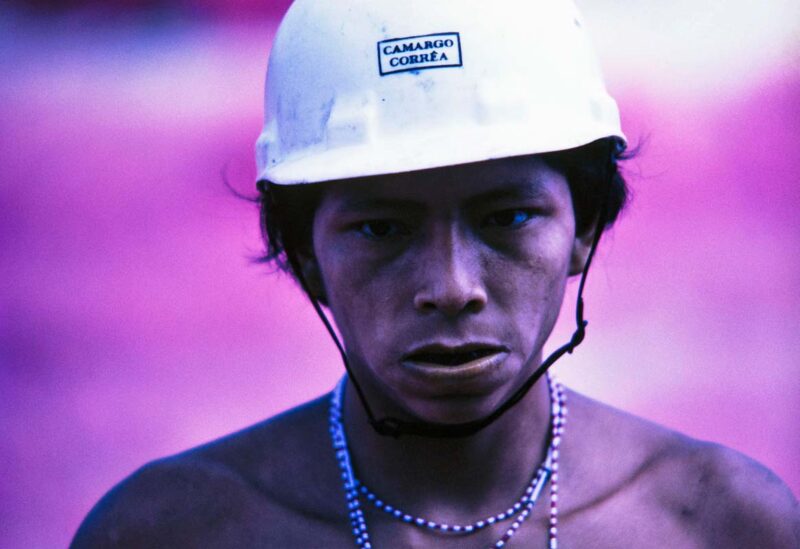

Three photographs draw our attention immediately. One is the portrait of a young man wearing a helmet working on a highway construction site. Nearby, two other photographs show what seems to be a dead body and the face of a woman, eyes closed, suffering from measles. These images remind us of the horrible disruption caused by the trans-Amazon highway undertaken by the military dictatorship in the 1970s. The highway was built in an attempt to bolster Brazil’s economic development, to the detriment of indigenous communities, and brought diseases including tuberculosis, measles, and influenza. It weakened the wellbeing of a people that was already seeing a calamity in the destruction of their forest-land (Urihi-a).

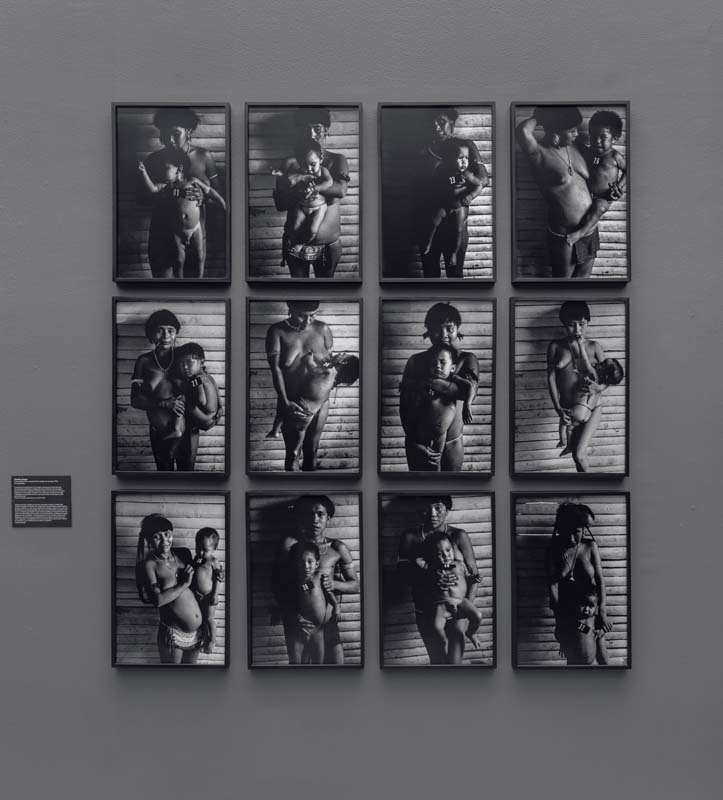

With the help of doctors, the CCPY organizes vaccination campaigns to protect against the diseases brought by the outsiders. The Yanomami keep no medical records – in fact, many don’t have a registered name – and so they’re difficult to identify. The only way to do this is to assign them numbers. Between 1981 and 1984, Andujar took photographs of individuals that were used to produce vaccination cards. When we look at these portraits, it’s hard to avoid the resemblance with victims of the Shoah – except that in this case the initiative made it possible to save many lives. The exhibition includes a number of images of these “marked” people – a sign of Andujar’s use of photography to seek a more humane world. As a friend of the Yanomami and through her art, she is involved in a struggle for their recognition. And it’s a struggle that is far from over.

Since the 1980s, prospectors have constantly invaded the area looking for gold. In addition to bringing their share of disease, they contaminate the ecosystem with mercury, which they use to extract gold from ore. The mercury is spilled into rivers, killing the fish and plants upon which indigenous populations depend to feed themselves. In this section of the exhibition, a video by the Forensic Architecture collective, produced in 2022 in partnership with the Climate Litigation Accelerator, inventories the incursions by illegal prospectors. This deadly situation was accelerated under the rule of Jair Bolsanaro (2019–22), and today it is the subject of an investigation into a possible genocide.

In the last gallery, an audiovisual installation covers the genocide perpetrated since the 1980s on these indigenous populations. Presented for the first time when the exhibition was shown in São Paulo, and produced in reaction to decrees signed in 1989 that

divided the Yanomami territory into nineteen separate reserves, the work transports visitors from a harmonious world into one devastated by the progress of “civilization.” The 1992 governmental decision, backed by the CCPY, that created today’s territory is constantly contravened by illegal gold miners. Made from photographs from Andujar’s archives, rephotographed with lights and filters, the

installation was created for this travelling exhibition.

In addition to presenting the work of a remarkable field photographer, Claudia Andujar and the Yanomami Struggle forcefully underlines the need to review humanity’s priorities with regard to ideas about progress. As Kopenawa notes, indigenous peoples have wisdom and knowledge that the world is only beginning to grasp. A growing sensitivity to ecology at a time when the world is in peril makes us realize that, like all indigenous peoples, the Yanomami are essential allies in the struggle against a capitalism that is responsible for environmental imbalances.