Alÿs has now made at least thirty-nine videos documenting children playing games throughout the world. The series brings together an absorbing collection of scenes – from middle‑class European neighbourhoods to the dusty backstreets of central Asia – that recollect ways of inhabiting the world that many of us have forgotten. Given that the videos are presented in a modest documentary style and reflect a global perspective, we may suppose that Alÿs’s project embodies the anthropological ambition of saving experience itself, in particular the event of childhood, which is now being degraded in the world of technics.

However, Alÿs’s perspective is advanced at ground level, where the simple and the modest invite us to attune our modes of attention appropriately. That is, we need only to wait while the children “play” with our world. The children’s game playing reinstalls us in a space of “free time,” if only temporarily. This is something that specialists such as the cultural historian Johan Huizinga and the psychoanalyst D.W. Winnicott have identified as the basis of creativity, which for both of them means “aliveness.”

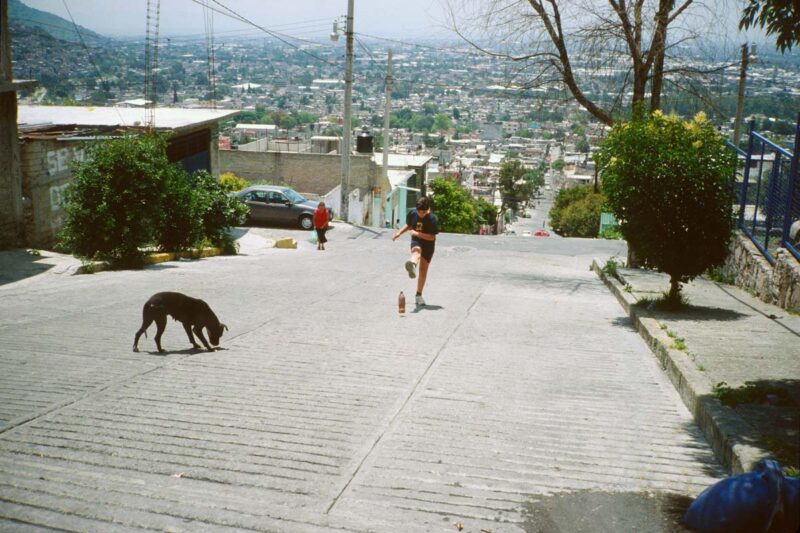

An engaging example is Alÿs’s Children’s Game #12: Musical Chairs (2012), a game known worldwide, here being played in Oaxaca, Mexico. This particular event involves six girls and boys and five chairs, but what is remarkable is the camera’s sensitive attention to the characteristics that make play what it is, including attributes such as spontaneity and aliveness. Musical Chairs is absolutely compelling, engaging us with this joyful but edgy race to gain a chair, the odds of which diminishes with each go-round, in harmony with the syncopated music, until the last chair is gone and nothing remains but the bare ground. The presentness of play, here, merges with the rule-bound structure of games in general. The overhead camera position effectively reveals the alternation taking place between the freedom that play is and its relationship with containment by rule and by chance. If within this relationship of “free play” and “rule” there is the potential for conflict, the video shows it being resolved in the excess inspired by the joy of playing. It seems possible to consider this

as Alÿs’s formulation of the oscillation between creativity and art, and our own place within this scenario. That this game arrives at a point of emptiness is significant; it is a source of enduring excitement.

A foremost aspect of play that Alÿs took up in the early days of his practice was recognizing the vital role that

purposeless activity performs in contemporary art. A compelling example of this is his 1997 performance Paradox

of Praxis 1, in which he pushed a large block of melting

ice through the streets of Mexico City. Commenting on the “unreasonableness” of this activity, he said, “Sometimes making something leads to nothing.” This is the kind of “simplification” by way of paradox that he often employs, and it serves as an example of his ongoing ambition to find or invent new forms of rationality modelled on poesis.

This performance with the block of ice “strikes us dumb” with its apparent uselessness, and yet this “stupidity” proposes an abundance of pleasure, of the sort that arises when we can let go of the desire for identity, accomplishment, “getting it done.” We could look at this performance in its kinship with those other art forms, dance and music, in which we can see that the song is in the singing.

Many of Alÿs’s actions have taken place in the ordinary environment that is the city street. From early on, he has favoured locations where the fast and smooth pace of current technology has not erased the sense of a local texture – places such as Afghanistan, rural Mexico, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. These sites still present the potential for there to be an “outside” or an “elsewhere,” the provisionality that is a source from which he has worked his “fables.”

Another key aspect of Alÿs’s practice is that of “the walk,” which often takes the form of meditative urban strolling, the kind of activity that tends to integrate one’s interior monologue with unexpected intrusions that occur in public places. As he travelled the world looking for kids playing, he found a great variety of physical and mental activities: a girl hopping along streets and sidewalks (Children’s Game #23: Step on a Crack); Afghan boys running with tires that they’re pushing with a stick (Children’s Game #7: Stick and Wheels); a Belgian group attending a snail race (Children’s Game #31: Slakken).

This space of the commonplace was the kind of site in which Alÿs encountered his first glimpse of the scenes that inspired the Children’s Games series, beginning with a chance encounter in 1999. The “retrospective” beginning of this body of work with Children’s Game #1: Caracoles (1999), brings to light the non-linear aspect of his process; the series formally began in 2007, with Children’s Game #2: Ricochets, filmed in Tangiers. At this point he apparently wanted to be “historical” by forming an anthropological archive of what he considers to be vanishing universal customs: the child’s game and the phenomena of play.

Some of the games included are familiar, such as Children’s Game #10: Papalote (2011), Children’s Game #16: Hopscotch (2016), and Children’s Game #20: Leapfrog (2018), whereas others are relatively unusual or site-specific. Papalote (Kites) presents a child, an Afghan boy about ten years old, in command of a traditional kite. He stands stalwart, manipulating his kite strings with total concentration and an elegant precision. Is he firmly grounded by what he doing, or is it the other way around? Flying the kite is rooted in his being present in the here and now. The scene is one of deep beauty, integrating simplicity, modesty, and intimacy. There is a flow, a fluid connection, among the kite, the wind that carries it, and the child’s bodily engagement.

The interplay of hands is a focal point in many of the videos. Perhaps this is where the question of distinguishing children’s games from sports arises. None of the games Alÿs has documented so far present aggression or competitiveness in the sense we know from the adult sports industry. Still, some of them show what appear to have been intense moments for the participants. For example, Children’s Game #29: La roue (2021) documents a game being played on the site of a mine, a massive industrial environment complete with a volcano-shaped slag heap. Here, a group of boys have brought a large truck tire to the site and roll it up the side of this veritable mountain of cobalt debris. When they reach a height that would provide a good “run,” one of the boys wedges himself inside the hollow of the circular form, and the tire/boy takes off down the mountainside. In the video, some of the scenes that capture this rush down the rough surface are shot from a camera inside the tire. When a run is over, the players simply restart the process, rolling the tire back up the hill – the kind of repetition also seen in some of the other videos. And again, as with the boy in Papalote, the expressivity of their faces and their bodily gestures is remarkable in its aliveness. We can clearly see how serious the game is for the children, and this is somehow amplified by the fact that play is gratuitous, done for its own sake rather than for some concrete gain. They do it out of the pleasure that doing it is.

What we see here, in these videos, is as good as it gets in life. From here we are not going to improve ourselves through conventional historical “actions” such as work, meditation, advancing a career, and so on. The path from childhood to the adult world is analogous to that of art in its relation to the everyday world of instrumentalities. The play in these games shows us a kind of peak point in life, and this is something that play, games, and art have in common. The richness of being alive with others that appears in Alÿs’s Children’s Games offers insights pertinent to the humanist concern with experience and embodiment as a mode of being now being lost.