[Summer 2024]

On the Road to Nowhere

by Julie Martin

[EXCERPT]

What story can photographs tell?

How can a performance be reconstructed?

How can travel be recounted with still images?

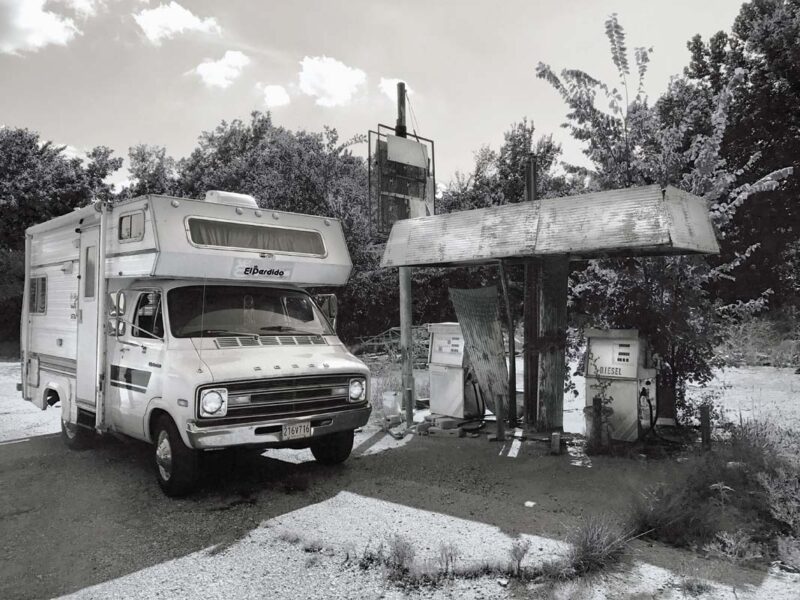

These questions traverse the histories of performance and of photography, and are at the core of the work of the artist Patrick Beaulieu, who updates the approach to both media by linking them in a highly unusual poetics of travel. When he climbed into an ageing camper van dubbed El Perdido in summer 2017, he didn’t have the slightest idea where he was going. This project continues the tradition of elegiac excursions that he has been taking for a number of years, including the transborder odysseys during which he followed the migration of monarch butterflies in 2007, was impelled by winds in 2010, and took a chance with a wheel of fortune in 2012.

This time, Beaulieu went in search of places that don’t exist. He started out in Lost City, asking everyone he encountered about a place called “Forgotten Road.” Surprisingly – and absurdly – this protocol drew him along the byways of Oklahoma and Texas and then, the following year, to Mexico, where his trip ended at Paseo No Me Olvides (literally, “Don’t Forget Me Walk”). To recount his voyage, he chose to display its significant objects in an exhibition: his vehicle, camping equipment, and the books he had carried with him. He also visually documented his wanderings through videos and photographs.

A first series of pictures shows a heterogeneous grouping of signage, composed of traffic signals, signs, and arrows. A good look at them tells us nothing; they’re pretty useless if we’re expecting them to provide some information. Many of the huge billboards are empty; the postings remaining on some of them are in tatters; some signs are upside down, others devoured by rust; direction arrows, which we suppose may once have been lit up, point toward the ground.

The signage is no longer able to fulfil its function and renders all meaningful travel impossible. The overall effect is one of disorientation and drifting. Between Oklahoma and Mexico City, the places resemble each other so closely that it’s as if one hadn’t travelled at all: everywhere the same undulating metal roofs and plastic trash; the electrical wires running, unvarying, from pole to pole; too much ineluctably identical mesh fencing and barbed wire. Once full of life, these places are now deserted, marginalized, quite forgotten. On board El Perdido, the usually romantic, even heroic dimension of the voyage subsides, giving way to pointlessness and becoming a deliberate meandering through spaces often deemed uninteresting, insipid, ugly.

The history of North America is determined by travels: those, conquering, of the colonists; those, forced, of Indigenous peoples; those of slaves deported to be exploited in the cotton fields; later, those of farmers thrown out of work by the financial crisis. The United States welcomed a huge number of European migrants in the early twentieth century, before quota laws kept them and, later, populations from the southern part of the continent from travelling once they were there.

These severe laws stand in opposition to the freedom of movement that local populations enjoy, in particular thanks to cars. Indeed, cars have replaced carts, horses, and trains – which played an essential role in conquest of the continent – and left their mark on society; since the 1950s, mobility has been an expression of modern life and social success. The road trip became the perfectly American form of travel, popularized in literature and, especially, in movies. Mass tourism finally tamed and restored the vision of travel around North America. And today, travel agencies sell customized tours to people in search of adventure.

Beaulieu goes counter to this dynamic, choosing to cast his eye far from sites that evoke the nation’s history and from natural and architectural curiosities and keeping away from spectacular recreational landscapes. In his pictures, he erases neither the peeling paint nor the cracks slithering across the asphalt, nor, even less, the electrical wires looping across the sky. Like a clue left to viewers, the book Being Elsewhere tucked into glove compartment of the vehicle, itself a perfect emblem for touristic mobility, reminds us that tourism has historically been composed of social distinctions, a consumeristic relationship with the land, a frozen history of the country.

Yet, from these places without obvious charm Beaulieu is able to produce images with a precise composition that suspends time. Glimmers of red – on an arrow, a billboard, a car, or the stripes of the American flag – draw our gaze to what doesn’t usually catch the eye.

Above all, just as weeds grow in cracks in the asphalt of neglected roads, something unexpected and invigorating springs up on the road: the goodwill of those who go out of their way to assist the apparently lost driver. The arms and hands of people pointing out directions are captured by a camera placed overhead, on the roof of the camper. In the images obtained, the clothing and accessories of these improvised allies testify to activities suspended for a moment to approach the vehicle and help out the bewildered traveller. All the gestures testify to their solicitude.

A quest “can take the form of a face,” wrote Alexis Pernet. In many of his expeditions, Beaulieu chooses to take along acolytes, who bring their expertise. This time, it’s the geographer Alexis Pernet who climbs on board; every day, he records words in a travel diary. These words accompany Beaulieu’s photographs in the book that is one of the forms of the project’s reconstruction. Although the angle of the photographs doesn’t show us faces, preserving people’s anonymity, the texts sketch out short portraits of these encounters. One looks on a map; another finds the destination requested on a smartphone. Someone searches the internet and makes numerous phone calls. These various investigations generate a profusion of words, of sharing, leading to more or less confused directions; the travellers, very happily, remain disoriented.

With the advice they receive, they will be able to lose themselves more thoroughly, make detours and U turns, washing up in dead ends. “No me olvides” implores the final billboard of the trip, found in Mexico City. In this project, words and images join together to conjure forgetfulness, yet keep traces of those who have been met along the way. Beaulieu throws himself on people’s mercy, counts on their kindness, and pays tribute to their generosity.

A pure loss, then, but one in which there is surely much to win.

Translated by Käthe Roth

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 126 – TRAJECTORIES ]

[ Complete article, in digital version, available here: Patrick Beaulieu, El Perdido — Julie Martin, On the Road to Nowhere

]