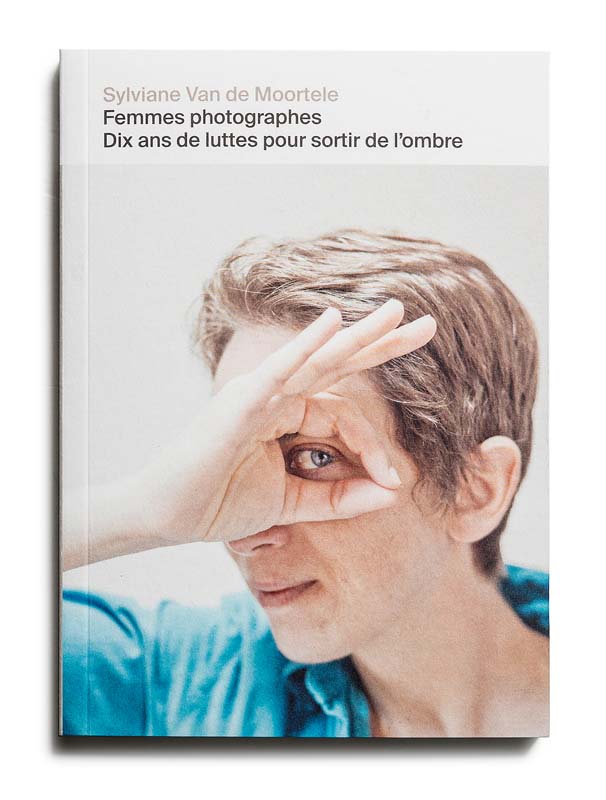

“When a feminist is accused of exaggerating, she’s on the right path.” The epigraph announces what is coming. In Femmes photographes. Dix ans de luttes pour sortir de l’ombre, Sylviane Van de Moortele describes the battle fought by women in France against the erasure of their sex in the field of photography. This “book of photographers without photographs,” more an account than an essay, brings to light the major effects of a decade of mobilization.

On April 6, 2014, an open letter was addressed to Jean-Luc Monterosso, director of the Maison Européenne de la Photographie (MEP): “You are a stakeholder, an essential promoter of contemporary photographic creation. Your influence and responsibilities are important, and that is why we wish to share one of our concerns with you. Since 1996, the MEP has presented 280 solo exhibition, and 82.5 percent of them have presented work produced by men. . . . The MEP is 80 percent funded by the Ville de Paris. Public money cannot continue to serve an obsolete old boys’ club, feeding a system that perpetuates factual discrimination with no rational justification.”

Signed by Vincent David and published on the Atlantes & Cariatides blog, the letter hit its target. A dialogue with Monterosso ensued. The subject was on everyone’s lips at vernissages, where David was lauded for having triggered the debate sensibly and eloquently, without resorting to divisiveness.

In the wake of the open letter, Monterosso invited the photographer Marie Docher to organize a roundtable. Ni vues, ni connues ? Comment les femmes font carrière (ou pas) en photographie [Neither seen nor known? How women make a career (or not) in photography] was held at the MEP on October 28, 2015. That very day, just before the event took place, Docher revealed to Monterosso – with whom she had been collaborating for months – that Vincent David and she were one and the same person.

Beyond this lightning bolt, the roundtable was a tipping point. The encounter, which Monterosso later called “breaking through the unthinkable,” brought people from the fields of education, sociology, and promotion together to size up the collective unconscious that perpetuated the invisibility of women photographers. What followed was a decade of efforts, marked by remarkable advances. This is what Van de Moortele tells us about.

Docher, a photographer, author, and activist, was engaged on several fronts with a single objective: fair representation of women in photography. She launched the Atlantes & Cariatides blog in 2014 to create a space for conversation. Intuiting that men were not inclined to read texts written by women (a fact corroborated by a Goodreads poll reported on by The Guardian that year), she concealed her identity behind a male pseudonym.

In 2015, she approached Van de Moortele (writer, biographer, and co-founder of Villa Pérochon – Centre d’art contemporain photographique in Niort) about an event organized by the centre and featuring women photographers. In 2021, Docher asked Van de Moortele to write about this struggle, in which she had been joined by others over the years.

Van de Moortele delivers an account buttressed by the personal stories of twelve people particularly concerned by the issues in question. Ten women and two men (artists, festival organizers, curators, researchers, civil servants from the Ministère de la Culture) agreed to be interviewed by Van de Moortele, who emphasizes that the preponderance of women is due not so much to deliberate choice as to the refusal of the men contacted to participate (or their lack of response).

In one chapter per year from 2014 to 2022 (as well as another devoted to the antecedents of the struggle between 2009 and 2013), Van de Moortele writes about the successive victories and the obstacles encountered along the way. The cause quickly resonated beyond the field of photography, and Van de Moortele brings to light the entanglements with art, activist, academic, and political circles. A network was woven and there were concrete impacts. Magazines and festivals began to focus on women photographers, and associations were formed to promote their work. The movement reached as far as the Ministère de la Culture, where the French government’s equality roadmap was supported by a senior civil servant particularly sensitive to the cause.

In 2017, the magazine Fisheye published a special issue titled Femmes photographes, une sous-exposition manifeste, accompanied by eight demands and a manifesto endorsed by some eight hundred signatories. In 2018, the website Visuelles.art presented a series of filmed interviews dealing with questions such as “Why is gender important if only talent counts?,” “Does showing more work by women mean a lowering of quality?,” and “Why are there so few women in art history?” To raise the visibility of her new platform, Docher distributed leaflets at the Rencontres de la photographie d’Arles. “Again this year, 80 percent of those exhibited are men,” she wrote, “and we at Visuelles.art will explain why.” Sam Stourdzé, the festival’s director, retorted, “You’re interfering with the festival and you don’t know how to count.” Indeed, their figures didn’t match up: Docher had included group exhibitions, whereas Stourdzé had not. Two months later, the daily Libération published a letter calling out Stourdzé, supported by five hundred international personalities and signed by the newly formed collective La Part des femmes, whose spokesperson was Docher.

In 2020, the fight was expanded to photojournalism. La Part des femmes inventoried the photographs published by French national dailies and concluded that 92 percent of the images were made by men.

In example after example, Van de Moortele points out the firepower of Docher and her cohort. Docher started “counting so that women count” in 2014 because some of her colleagues doubted that men were overrepresented in their profession. In 2019, Marion Hislen (photography delegate at the Ministère de la Culture) mandated her to update her data. The exercise showed progress. In Michel Poivert’s book 50 ans de photographie française, de 1970 à nos jours, published in 2019, more than 40 percent of the photographers he discusses are women. It was “a change of paradigm in the history of photography,” Docher observed.

The 2019 program of the Rencontres d’Arles boasted near-parity. Docher wrote an emotional letter to Stourdzé the following year, when he resigned as the festival’s director: “In 2019, your program had parity in the solo exhibitions and you showed that an egalitarian festival suffers no loss of quality. . . . I received your program last evening. . . . I will be sincere . . . but more private, because the private is political. I felt joy, I danced, I cried, I’m still weeping with emotion. This program is rich, diverse, and signals a radical change. I hope that it will serve as an example.”

“History has been written by men, with a male gaze that has obscured women, leading to silence and omission,” Van de Moortele writes. “The idea of reintroducing them into the weft of history is not simply a feminist issue. It is, first and foremost, a demand for truth.” She invokes the historian and feminist Michelle Perrot and broadens the idea to other spheres. The erasure of women and inequality are not the sole prerogative of the field of photography, and the scope of actions taken over the last decade goes beyond its borders.

“This work will do two things,” says Docher, to whom Van de Moortele leaves the last word, “to define the problem and to make it so that no one, no curator, can now get away with not thinking about this, with not asking questions.”

This important struggle is not, however, over. The obstacles encountered by women aged forty and older (the further they advance as professional photographers, the less they are seen), the absence of women from photography schools, and the concomitant perpetuation of a feeling of illegitimacy (as a consequence of which many women choose adjacent careers, such as curator, critic, or exhibition designer) are some examples.

Van de Moortele does honour to this struggle in her book. She also encourages those who would like to take part; by condensing ten years of fruitful effort into a hundred and fifty pages, she lets us gauge the field of possibilities.