[Summer 1994]

by David Hopkins

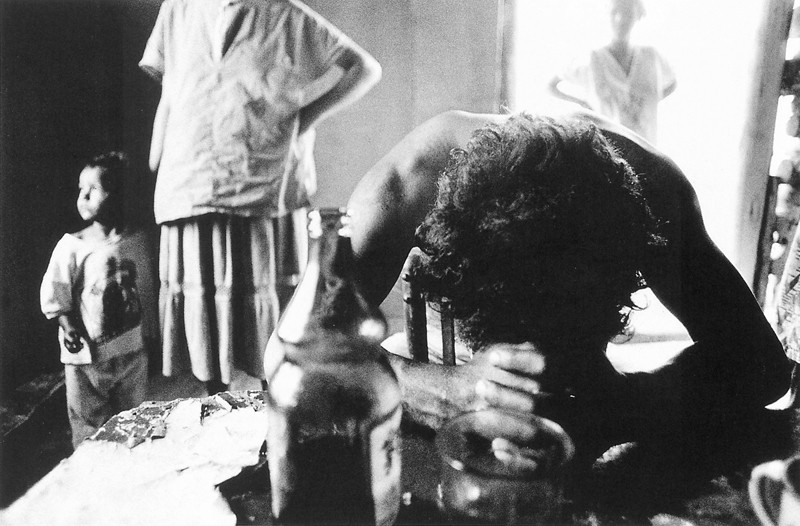

A weary man leans on the table — worn out from what appears to have been a sleepless night of heavy drinking. We are drawn into the drama. A woman stands in the doorway in the glaring morning light with her hands on her hips.

Each of Zimova’s most recent portfolios is motivated by the desire to record aspects of daily life in one of several fragile, struggling cultures. Her photographs go beyond a superficial record and engage us with her unique vision. Each portfolio appears shaped by a fresh response to the character of each community.

In the last three years, her portfolios have dealt with the Gypsy settlements in Eastern Slovakia & Romania, with life in isolated Banat Czech communities in Romania, and, most recently, with selected communities of native peoples in Northern Quebec. In the introductory texts to her portfolios Zimova writes that she wants to “document the communities as they are now.”

This urge to witness seems motivated by an appreciation of history and tradition, and by a concern that the dominant communities surrounding these more fragile ones are effecting changes in their culture and social character; the transformations to which she refers occur as the result of contact with outsiders or the deliberate efforts by the more dominant cultures to rapidly overwhelm and assimilate them.

In the case of the Gypsy communities, community members have managed to maintain their racial identity and traditional lifestyles for centuries, despite repeated attempts by the Czechoslovakian and Romanian governments to assimilate them. Zimova anticipates that the recent political changes in Eastern Europe — along with the rebirth of nationalism and racism — will profoundly affect the future of these communities.

The Banat Czechs are the descendants of a group of traditional Czech people that emigrated to a remote region of Romania in the 1800’s. They have preserved the traditions, lifestyle and values of their forefathers, despite cultural and geographic isolation from both their homeland and the influences of the Romanians that surround them. Their relative seclusion and self-reliance has perpetuated centuries-old ways of subsistence farming, puritanical values and the common use of Old Czech as their spoken language. Zimova sees the effects of economic ruin and political instability in Romania gradually infiltrating this community.

Iva’s latest work-in-progress is a portfolio documenting the natives of northern Quebec. Included in the portfolio are photographs of the Inuit of Kuujjuarapik (Great Whale), the Naskapi of Kawawachikamach (Shefferville), the Montagnais of Matimekosh (Shefferville) and the Maliotenam (Sept-Iles.)

In the introductory text to the portfolio she writes that the indigenous people of northern Quebec had a deep spiritual relationship with the land and the life-forms it supported. She believes that the European newcomers disrupted this balance, and that, more recendy, the increasing interaction with Southerners has been detrimental to the native peoples’ environment, economies and social structures. She hopes to record their present lifestyles and their struggle to connect their ancient cultures with their present-day reality.

In all three portfolios she succeeds in her primary mission of documenting the current lifestyles of the different groups examined. She witnesses the social occasions and rituals: births, baptisms, spiritual ceremonies, weddings and funerals all play a role in the portfolios. She also records the more informal group and personal activities of her subjects while consciously including the physical context of the action. This material, along with the myriad incidental clues, weaves a broad visual tapestry of each culture. However, she also goes beyond her stated objective by introducing her personal vision and style to the document: her keen level of observation and the quality of her interpretation give the portfolios a greater depth.

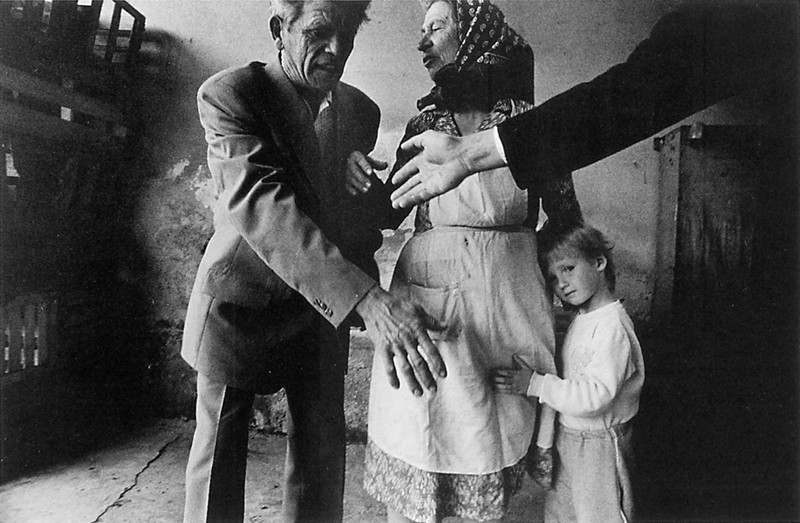

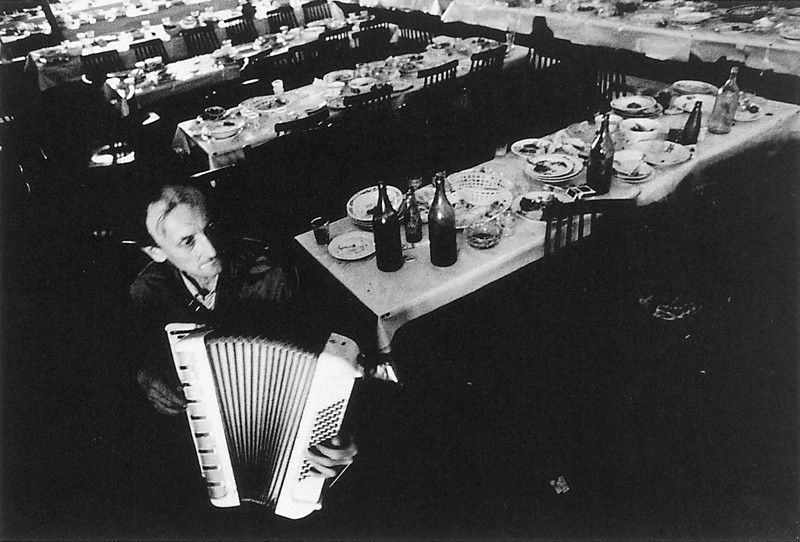

In the Gypsy portfolio, her approach is bold, intimate and often technically raw. The pictures appear to have taken on the character of the community: the harsh tones, coarse grain and rough contrast evoke the community’s day-to-day struggles with alcohol, poverty and lack of opportunity. Her framing and timing show a conscious effort to develop associations between the various people or elements within each picture. This works on a formal level, and also as a means to suggest a story or drama to the viewer.

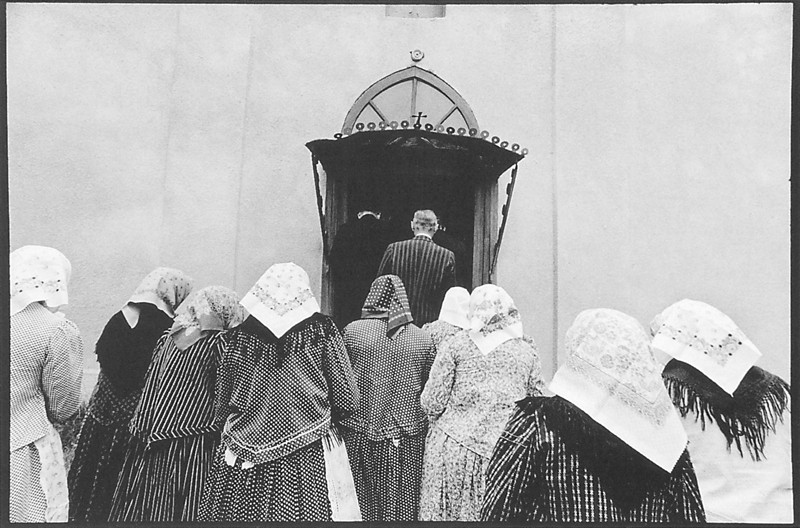

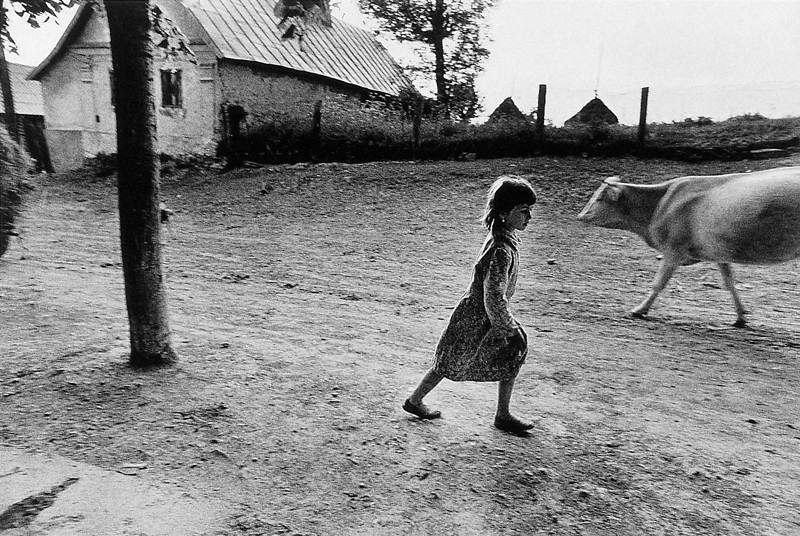

In the tradition-bound Czech community, her style is more tempered. This is a less intimate community — one that highly values tradition, church, labour and formal relations between children an adults. Appropriately, her style changes with the people: the roughness, the bold intimacy and harsh contrasts are gone. This portfolio displays a more classical documentary style — observations are made from a greater distance; the light and contrast are quieter; and a more understated interplay of elements animates the pictures.

Despite the more muted approach of this portfolio, there still exists a strong undercurrent of keen observation and love of juxtaposition. Through her framing and timing she intensifies the significance of incidental gestures to reveal her characters and — by extension — the community. This is particularly evident in the photograph of an elderly couple and young boy, frozen at the precise moment when their hands reveal the relationships between the people and form an ideal visual structure. The dark sleeve, white cuff and bold reach of the foreground hand are evidently those of a stranger reaching across the frame. We are drawn to the awkward hand of the old farmer, the cajoling hand of his wife teasing him, and the tender hold of the young boy’s hand on his grandmother’s dress.

In the absence of the debilitating alcoholism and poverty of the Gypsies, Zimova seems to have relaxed, often finding occasions to display her sense of humour. Her picture of the little girl and the cow on the dusty main street of the town is a good example of how she can document the rustic and agrarian character of this community while at the same time taking the opportunity to have a little fun.

In her latest portfolio she has replaced the mellow light, heavy textures and tight space that evoked the Eastern European with lighter tones and a more open, formal style. A greater sense of space accompanies the change of continent: the North is often viewed from a lower camera angle to include an expanse of open sky or the white walls of canvas tents. Iva is still intent on documenting the community, yet she places an increasing emphasis on the graphic and structural organization of the images. The cigarette held horizontally in a woman’s hand is now less emphatically a brazen symbol of addiction to tobacco; it works more as a visual counterpoint to the repeated vertical lines of the nearby fence and tent poles. In keeping with the new style, the pictures of this portfolio are less intimate and less emotionally charged than those of her prior work (although she makes an exception to this pattern in her coverage of the funeral of a murder victim).

Zimova is spending the winter in Kuujjuarapik (Great Whale). The short days and bitter cold may have partly inspired her next project (in Mexico City, where she hopes to document life in that city’s slums). She suggests that the pollution, failed infrastructure, poverty and overpopulation of this enormous city are examples of what may befall all of our expanding Western cities.

Iva Zimova holds a BFA in photography from Concordia University and is a graduate of the Dawson Institute of Photography in Montreal. She has participated in numerous group shows and has had four solo exhibitions since 1989. Her portfolio The Forgotten Czechs of Banat was supported by a grant from the Canada Council, and she has received funding from Le Ministère de la Culture du Québec for her work on the natives of Northern Quebec.

David Hopkins teaches photography at Dawson College in Montreal, and has published articles in the magazines Camera Canada and Camera & Darkroom.