[Spring 1994]

by Manon Gosselin

It swells within, beyond all containing. It revives. The humblest of creations dialogues with nothing but the metamorphoses that it attracts by virtue of its own mystery. Beyond revolt. Beyond reconciliation.

⎯ Jean-Luc Godard, 1987, Soigne ta droite

…and in his shadow, never leaving him by so much as an inch, “I didn’t touch him. I didn’t go very near him. He would be as cold as ice and as stiff as a board. ”

⎯ Chandler

In his shadow, I shall continue to look at the moon that was unfolding.

we were dismembering people

we were cutting out their eyes

we were cutting off their ears

victim of a war

1991

First of all, a witness. Precisely there, in this dramatic state, the presence of the camera, this mechanical eye, is condensed: a persuasive and supplementary eye that keeps — always from a distance — residues of experiences, to be fixed by the light. Always a witness — but a witness of what, and a witness how. Let’s look back at these two scenes in the Ingmar Bergman’s film Persona (1966): Now the child caresses the huge photographic projection of its mother; now the mother covers her mouth with her hand as she watches a news telecast showing a man immolating himself in a public square. Fantasy and document. Two visual stopping-off points that become screen remembrances when we recall the film by way of these reference points.

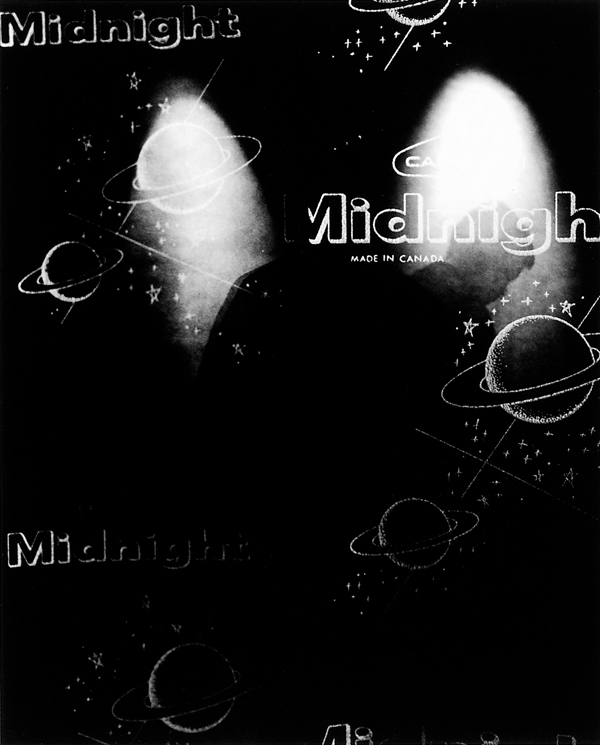

Louis Lussier’s photographs Testimonial Fabuleux (1991-…) are — for a start — sumptuous. There is an almost fanatical effort to test the aptitude for beauty that is reserved to the medium of photography. These are large photographs (although none of them attains commercial advertising dimensions). The 128 cm x 173 cm format is reminiscent of the idealized model represented in Vitruvius’ well-known study of human proportion, standing upright, feet apart, the arms outstretched, open, in the form of a cross. The persistence of this format — whether in the vertical or the horizontal (no. 2 and no. 6) — leads us to view it as something other than a technical expedient. Probably, a humanistic postulate is manifest in this format, scrambled and irradient: a political hesitation that is, perhaps, troubled at the same time by an impossibility of not being able to represent belief in the individual in spite of the discouraging realities of powerlessness, downfall, withdrawal, reserve.

Witness remembrance, screen remembrance. There is some of both. “Lussier’s photographic texts resist our attempts to definitively untie them; they frustrate our desire to decipher them through taxonomy, with finality. This is their great strength. For these phantasmatic images celebrate openness above all and preserve their aura of mystery at all costs. “1 And to truly see the price tag, we must permit ourselves the exuberant luxury of being marked — repeatedly and by whatever means — by the imbalance of a chaotic economy, the very same one that encourages multiple investments and retakes.

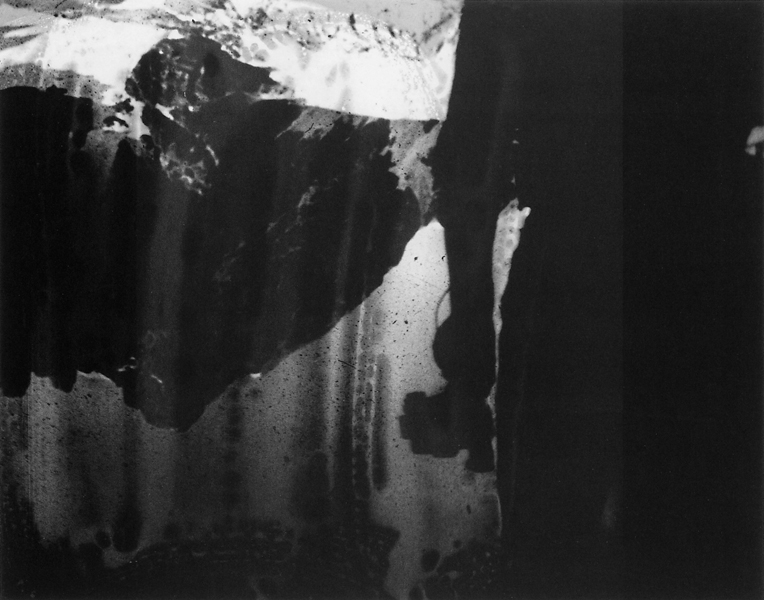

The setting is neutral, if not sordid (Testimonial Fabuleux no. 2). The horizontality (173 cm x 128 cm) is accentuated. A murky curtain, a psychotic transparency, a reversed mountain, a backdrop. In the foreground to the right, a masculine form (recognizable as such by the thickness of his arm) blocks the backdrop, the background, the mountain. This black silhouette, truncated, frontal, holds something in his closed hand. If it were a firearm, a rifle, the curtain would be tarnished; if it were a camera, the mountain would be even more pregnant with meaning and another signification would emerge. Fantasy and document. In what way is the screen there, and how (to reiterate Serge Daney’s reflection) can we see the screen in some other way than “as the bottom of a Tefal [sic] pan (of glass), ready to sear (culinarily speaking) …”2 the reality that is behind it?

The transparency is limited, hindered. The fantasy beclouds the document, it confuses the issue of the shot, the that was of Barthes. Not all is revealed at once, oracularly. It already was — but at different times; the photographer testifies to the fact by multiplying the exposures on the same negative, projecting, with a remarkable masterliness, his “after-the-event,” maybe his blueprint. So, the first image in abeyance finds itself melted by a new one — and each of them striving toward the quasi-discernible, toward obscurity.

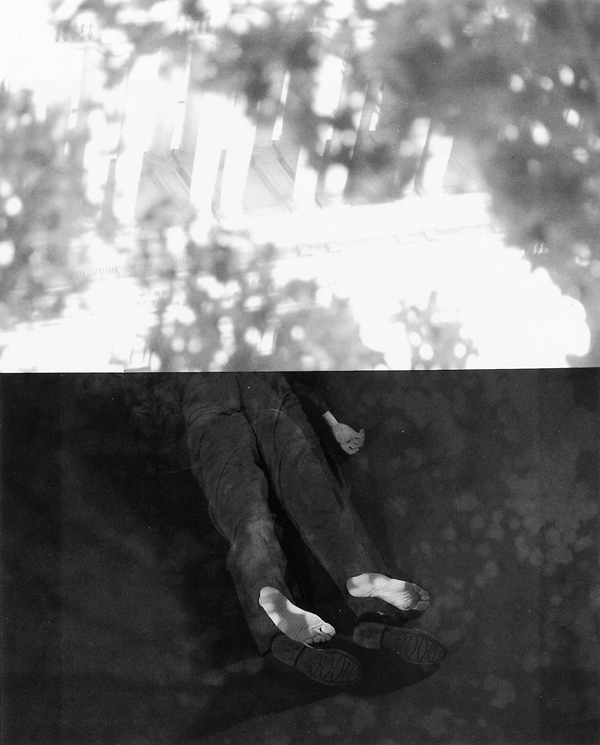

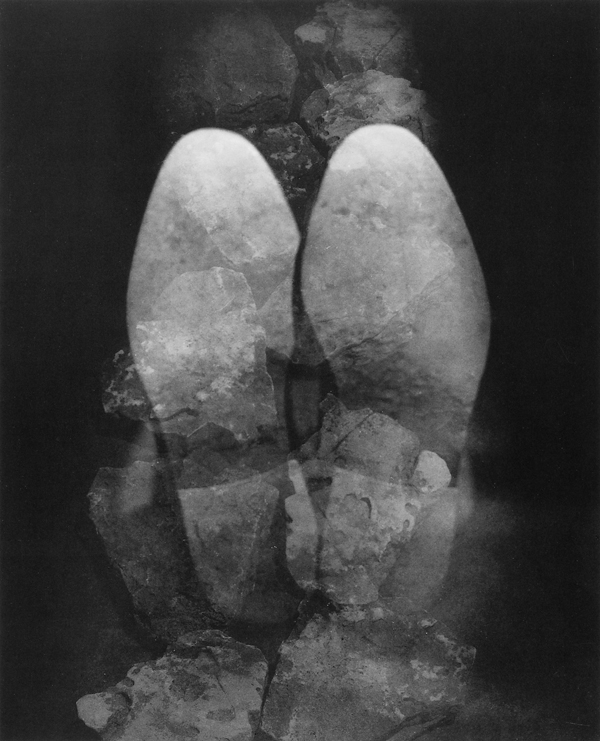

I would have a tendency to see, in this Testimonial Fabuleux3 collection, a photographic sequence rather than a series of photographs (a series having more to do with an order that is a conceptual variation of one or several determining elements). Undeniably, there is repetition, elements that repeat: shoes, soles, black silhouettes, fragments of men’s bodies, dislodged bodies, earth, moons. However, these photographic shots seem, rather, to make up the framework of a dramatic plot that was not determined in advance: a sequence of dead time, of screen remembrances whose narrative anecdote was exhausted by the photographer so that it could be taken up again by us.

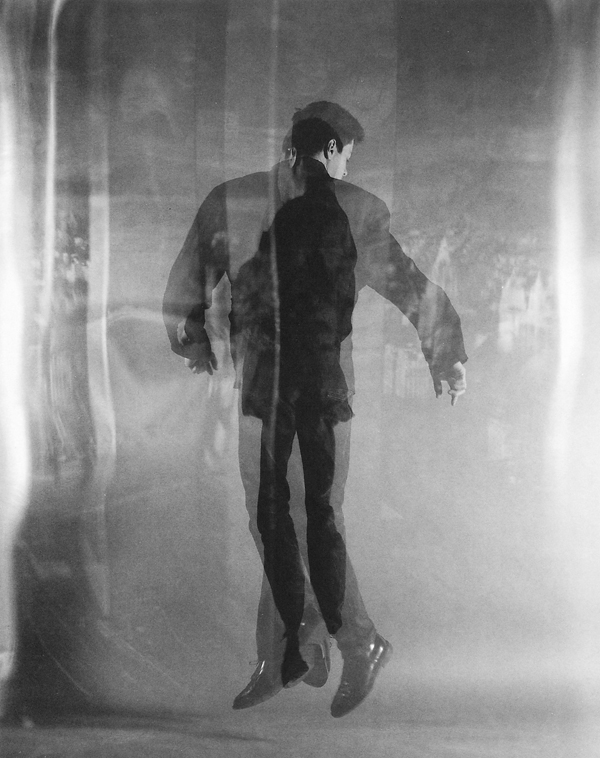

I-He. The photographer is the only model appearing in his photographs. In the excerpt reproduced from Testimonial Fabuleux that is before you, a single multiple-exposure photograph (no. 9) displays (or captures) the photographer’s head in close-up. This face is troubling. Another one (no. 8) offers it to us in a full-body shot, falling. The photographer makes use of himself and I see no narcissistic hang-up therein (if there is one, it is even more terrible). Anyway, Narcissus died, drowned, quite early into his years, because of his love of himself; here, it is more a question of a narcissistic suspension — and the check, the fall (no. 8), is the screen remembrance.

The photographer’s body is a character in the American, film sense of the term, close to the dramatic and aesthetic conventions of film noir: “… more a mask, a symbolic idea than a flesh-and-blood representation hardly move their facial muscles or their lips… “4 If there is an analogic perspective to probe between that film style and this Testimonial Fabuleux, it deserves a very special attention, the word quotation not having, in the case at hand, exclusive pertinence for the defining and mastering of it all. Beyond terrorism, beyond pillaging.

No Utopia of self for oneself, of intimate and self-centred searching. Throughout this Testimonial, the self-portrait — these fragmented and dislodged bodies — is impersonal, at the limit of self-effacement.

The work is not the self-portrait. Concurrent with this “quasi-discernible,” there is a shock and a deviation, and it is because of the manner in which the photographer introduces his own body into the image that the self-representation beclouds it. He is always the starting point of the metamorphoses. He subtilizes himself, makes himself up, takes himself for an object while politically observing an incredible distance. Which makes this face even more disturbing, recognizable in frontal close-up, thinly disguised, lips compressed: A face contained, condensed, tragic, half-heartedly examined, an I-He suspended.

1 James D.Campbell, “Speculations on Louis Lussier’s Recent Work,” in Testimonial Fabuleux [exhibition catalogue] (New York: Jack Shainman Gallery, 1992).

2 Serge Daney, La Rampe, Cahier critique 1970-1982 (Gallimard, Cahiers du cinéma, 1983), p. 37.

3 To facilitate this presentation, I was forced to assign page numbers to this Testimonial Fabuleux (which originally had none).

4 Foster Hirsh, The Dark Side of the Screen (A Da Capo Paperback, 1983), p. 7.

Hailing from Montreal, Louis Lussier is a self-taught practitioner of photography. Since receiving a bachelor’s degree in communications from the Université du Québec à Montréal, he has devoted himself entirely to his photographic work. His works are regularly exhibited in Canada and in the United States. Louis Lussier is represented by the Jack Shainman Gallery in New-York.

A native of Montréal, Manon Gosselin has studied visual arts and is currently writing a master’s thesis on the work of Jeff Koons. She has always been interested in the image and has concentrated particularly, for several years, on the work of Louis Lussier.