[Summer 1994]

by Stéphane Chagnon

Hidden behind Laval Street’s Victorian architecture and ground floor rooms filled with artefacts, Charlotte Rosshandler’s Montreal studio bears resemblance to a backstage scene. The tranquil room with its simple decor inspires one to become detached from the world outside, to leave behind interfering concerns. Here and there, but a few photographs to recall photography’s venture into the world.

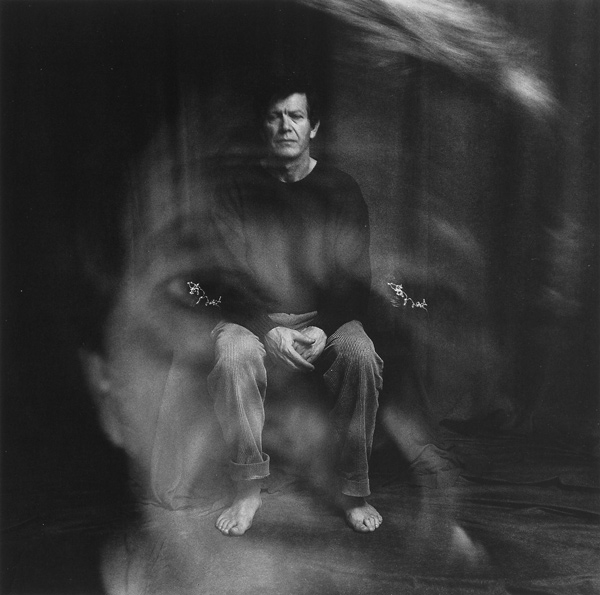

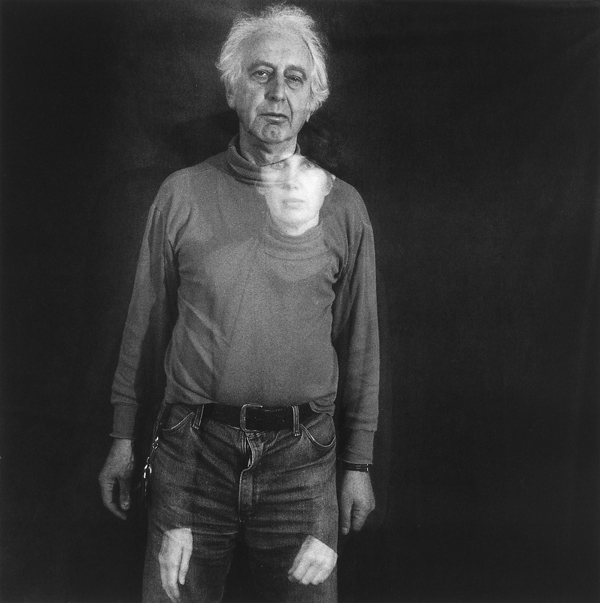

A black curtain hangs as a backdrop, revealing where, for seven years now, Charlotte Rosshandler has been producing photographic portraits of artists, friends and acquaintances. With Rosshandler, the photographic gesture is in many ways a denial of the utilitarian attributes that often define portraiture, materially immobilizing its subjects in rigid expressions. Each photograph taken is an action in itself, structured by its own evolution, experience and emotions. “My images are at times metaphors,” says the photographer.

Using her intuition and her sensitivity, Charlotte works with what Roland Barthes defines as “an affront of forces in close quarters” (champ clos de forces) in the photographic portrait1 of which intricacies she is well aware. She explains that “it is difficult to photograph people who have specifically made the request to be photographed. They come to me with a preconceived idea, and the experience is rigid, self-conscious, theatrical and all the more controlled.” In her quest for authenticity, Charlotte searches for ways to avoid these “photographic traps.”

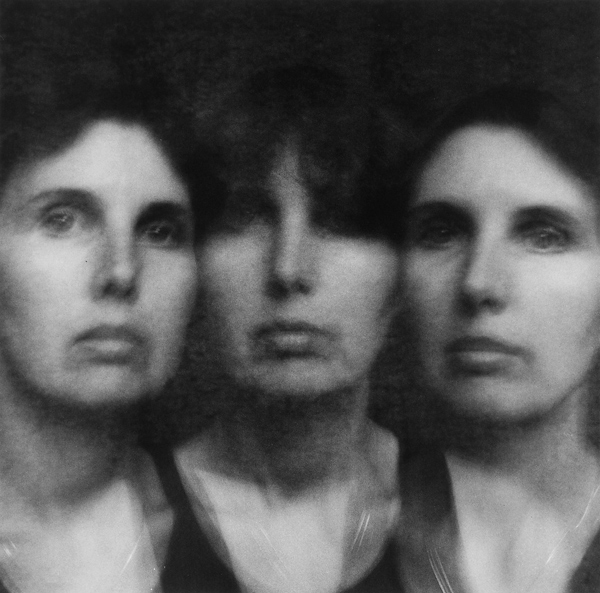

Throwing off the yoke of consciousness and opening the door to all unforeseen occurrences, the photographer probes the imaginary of the subjects she is photographing. Beneath the surface of the posing artist, she finds an individual, states of mind and the plural nature of beings. She discovers double, triple, quadruple beings who open up bit by bit.

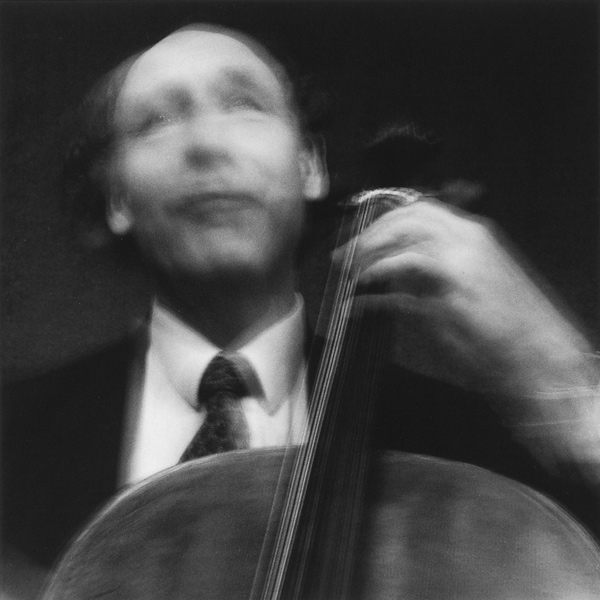

Charlotte does not assign objects to her subjects to “add life2“. Rather, she purposefully avoids the distraction of cumbersome accessories. Her prints reveal individuals unadorned by artifice in a spare decor. Charlotte Rosshandler’s photography captures both regards and body movement. As though disclosed by mechanisms of an inner dance, her subject’s very presence is expressed in traces of silhouettes, similar to the way a shadow reiterates the existence of beings and things.

One might be tempted to qualify this approach as ascetic, were it not for the extraordinary density it suffuses, which, through its sheer force, causes the photographic portrait’s very limits to shift and expand. A tremble in the image reveals the vibrations created by a cello virtuoso; we can almost hear the resonance of the musical soars that endow the subject with an ecstatic smile.

Charlotte Rosshandler’s current artistic practice is the result of a pursuit which, for over twenty years, has brought her to travel the world, with its different cultures. Each trip shaped into a true photographic journal. With time, however, her experience inspired her to seek closer ties with the subjects she photographed. Shying away from the bigger bustling streets, she began walking the paths leading to the Other.

The Montreal photographer turned next to the artistic milieu, going to and from artist studios in search of images. She scrutinized gestures and impregnated herself with the day-to-day lives of artists which were at once similar and different. The portraits of this period integrate the various elements that make up the subject’s world: his or her work, tools, belongings and regard. They quietly announce the mode of expression that the photographer would soon be reaching.

It is her will to define the creator’s identity that enables Charlotte Rosshandler to penetrate the secret of inferiority. “The portraits evolved according to my own personal queries,” she confided. From then on, the photographs are taken in her Laval Street studio.

Against the nakedness of the black curtain, prolonging the exposure time, Charlotte Rosshandler is able to capture multiple expressions as her subjects impart their evolving mind sets. “My camera has slowed me down to the point that the subjects are mobile on the negatives.” The individual’s complex nature emerges progressively.

This dimension of slow progression is of primary importance to the photographer’s work, as she describes: “I must watch carefully for signs of new expressions. Every aspect is an intrinsic component of the individual. Ignoring even one small manifestation could mean losing contact with the feeling as a whole.”

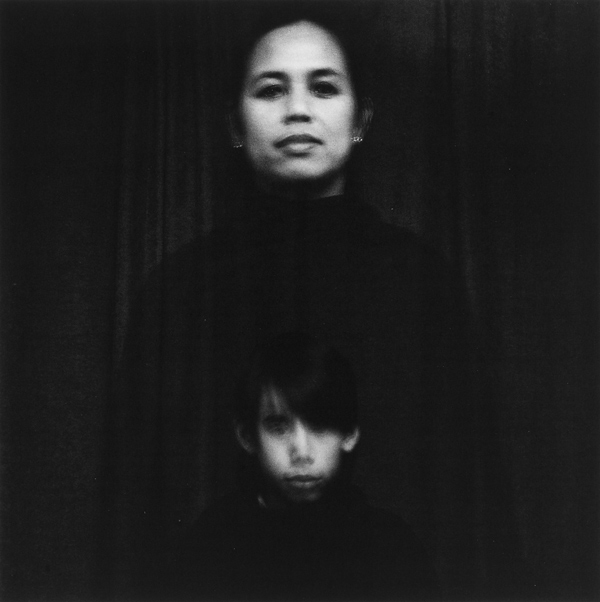

Charlotte’s concern with the integrity of interior experience reflects the manner in which she considers relationships between human beings. In order to truly ponder the individual, one must take into account his or her rapports with the outside. For this photographer, a hand affectionately placed on a shoulder conveys attachment, tenderness. She adds that “it is through others that we learn to discover ourselves.”

Her portraits express both traces of the body and presence of mind; they infer evanescence, evanescence of beings and of things. The subsequent transformations she works at capturing and fixing on film stress the passing of time, a time which may be perceived as a moving screen, revealing the facts to the watchful eye of an attentive observer. A temporality of changing expressions, of bodies in movement, but also of the succession of generations and of the continuity of the individual projecting him or herself into the act of becoming.

Some have remarked upon the similarity between the studied aesthetic of Rosshandler’s photography and certain involuntary effects caused by the lengthy time of exposure prevalent during the era of Louis-Jacques Mandé Daguerre. This particular quality undoubtedly contributes to the sense of nostalgia investing Charlotte’s most recent works.

Conveying the weight of temporality and the magic of art, the feeling of nostalgia is set in the emulsion, placed amongst the silver crystals.

Beyond the photographic act exists an even deeper quest, an intimate and fundamental search for gesture, the movement of life that breathes, that shifts in accordance to its own/inevitable issue.

Translated by Jennifer Couëlle

1 BARTHES, Roland, La chambre claire – Note sur la photographie, Paris, Cahiers du cinéma, Gallimard/Seuil, 1980, p. 29.

2 Ibid., p. 30.

Charlotte Rosshandler was born in New Orleans in 1943. She moved to Montreal in 1969. For more than fifteen years, her photographs have been reproduced in magazines such as Time, Vie des Arts, Saturday Night, Perspectives, 0V0 and ArtsCanada. Charlotte Rosshandler has participated in numerous group and solo exhibitions. In 1993, Montreal’s Saidye Bronfman Centre presented the first retrospective exhibition of her work. Covering twenty years of photography, the exhibition Questions & Portraits surveyed the evolution of her portraiture. Her photographs are part of public and private collections.

Director of the Centre d’art Rotary in La Sane, Abitibi, Stéphane Chagnon is also a curator and photographer. He holds a Masters degree in Museology from l’Université du Québec à Montréal and a Bachelor degree in Fine Arts with a major in photography from Concordia University. He writes for art magazines and exhibition catalogues and works as an independent curator. In 1989, on the occasion of photography’s 150th anniversary, Stéphane Chagnon was invited to curate the exhibition Regards sur la Chine.