[Winter 1994-1995]

by Martha Langford

She answered his request with the usual string of excuses. It was too late. He had asked her too late. Why had he not asked her earlier? She was too tired. She wanted to recite the rosary to the radio at seven. It was her way of teasing the child.

Was she more flirtatious now that he was older? He could not remember her any other way, in any other costume or scent.

You don’t really want to hear these old stories.

He placed the album in her lap. Her hands travelled over the cover. She fingered every scratch, every abrasion in the leather. Old scars, each one a history of careless dusting or no-business curiosity, a lifetime of maids sent away for stealing face-powder or smashing a dish. She followed them line by line across the cover; she would have had any one of them back, the most deaf, the most stupid, for the company of a woman in place of this wriggling boy.

Why was she prolonging this part of the game? His mind laboured furiously against reason. Closing his eyes, he felt his way back to their arrangement. Things were now as they had always been. She savoured the soup while he hungered for the meat. She smoked absently while they held back the dessert. She of the few remaining days tortured their every second into hours.

Grandmother, please.

She should have chastised him for his impatience. Instead, she opened the album and began to tell about the pictures.

I married your grandfather when I was seventeen. He was twenty-two, studying to be a dentist. He proposed to me on a trolley ride from Wychwood which was country then, all cottages.

Her body seemed to swell into the wing chair. He sat beside her and she turned the pages of the album, stirring like ashes the names and places of her account.

My cousin Annette – she was older than me and already married – her husband’s family had a cottage there and we spent the day and your grandfather proposed to me in the evening air, on an open trolley, as we rode home.

He had a flower, a brown-eyed Susan, tucked in his pocket. He took it out of his pocket and he began to pull the petals off. He pulled them off one by one, turning the flower, twisting the stem in his fingers as he whispered to me in a loud stage whisper, She loves me, She loves me not.

He spoke English. He always spoke of love and sex and marriage and dentistry in English. He spoke French to the children, French to his mother, French to the milkman, to the iceman, to the priest who married us, he spoke French to me in front of the priest who married us. But in secret, in our secret bedroom talk and in dentistry, he spoke English, and that evening on the trolley, he proposed to me when all the petals had been stripped from the flower and secretly, he changed my name from Marguerite to Daisy.

No one on that trolley was English, no one understood what he had said, but they all knew what had happened, what your grandfather had done, not with the flower and not with my name, but that he had proposed to me and that we would be married. Everyone it seemed was looking at me. No one looked at your grandfather. Everyone looked and nodded and grinned at me. It was me that was different and they all knew it even though they hadn’t heard him change my name from Marguerite to Daisy.

He waits in vain for the pictures of her transformation. No pictures, but arabesques on the Italian end-papers, and the inscription, undated, ‘To Daisy.’

He loved to take pictures, your grandfather, and he bought me this album to keep them in. He glued a heart into the album which came with a package of heart-shaped corners. They dried up and I replaced them one by one. They were not of good quality. See how poor they were and they left red marks where they had been on the page. But when the comers lifted I could change the pictures so I did as I liked certain pictures more than others and your grandfather liked me to do as I pleased with the album. He left it to me to arrange the pictures he made as I pleased.

She turned the page and began at last to tell the stories.

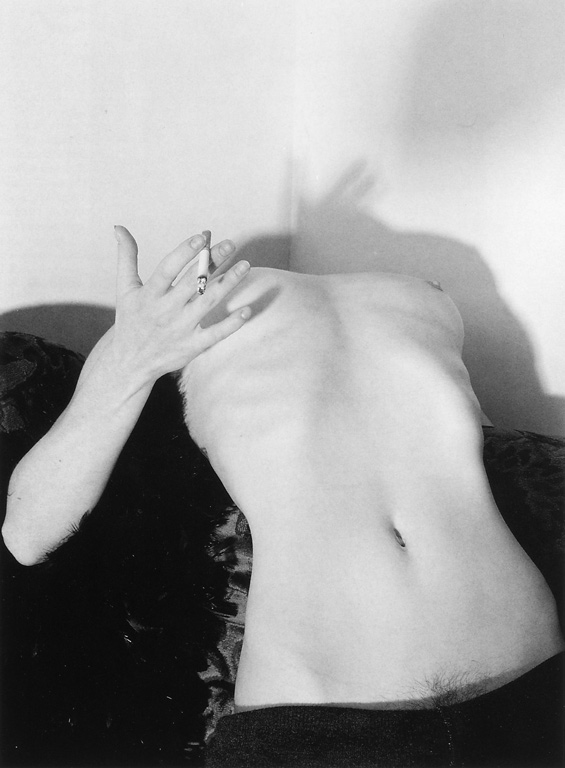

This was from a girl that we hired to take care of your father. She said she was Irish from Ireland. She said her mother was an acrobat. I never knew anyone from Ireland but I wanted a good Catholic girl to take care of your father. She was never from Ireland as she said and she went on her day off to visit her mother who worked in the kitchen at the hospital. The cook told me all about it but I kept the girl untU she came to me one day and told me she was leaving to work at the hospital with her mother. She told the cook that she was leaving to join the circus. She never changed her story. There was a story for the cook and a story for me and one day she simply switched stories and then she was gone and your father’s silver baptismal spoon with her. We found her little crucifix when we shook out the bedclothes in her bedroom. I showed it to your grandfather and he told me to keep it to make up for the loss of the spoon. We did her picture and the picture of her mother.

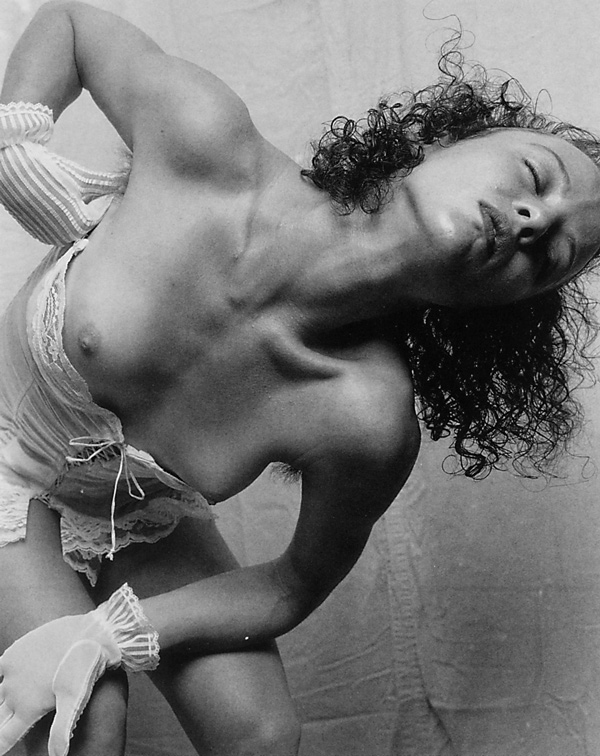

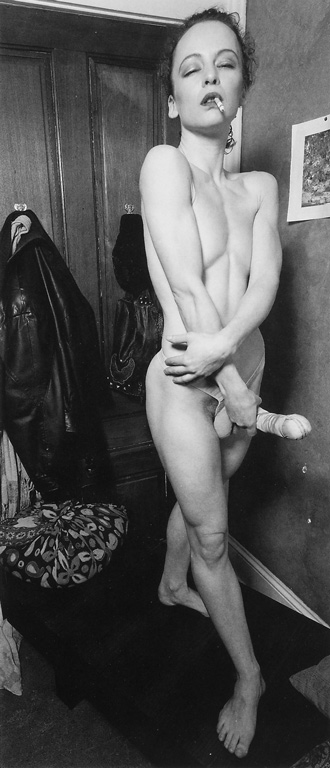

The little dancer was a patient of your grandfather’s. Terrible teeth. She came often to the office always fearful of extraction. Her mother hadn ‘t a tooth in her head. He saved her teeth or most of them but she had no money – no one had any money in the Depression – so she came to us on Saturdays to help with the heavy laundry. She and another girl who came from the country were supposed to do the heavy laundry and the ironing but things piled up in a terrible way and after a while I found her stealing an embroidered pillow case and so I let her go. Your grandfather was very angry with me but the lace on that pillow had come from my mother so there was nothing more to talk about. She had to go. We had nothing of hers because she only came on Saturdays and never even changed her clothes. She was a dancer – that was what we knew – and her teeth were terrible, so we did what we could with that.

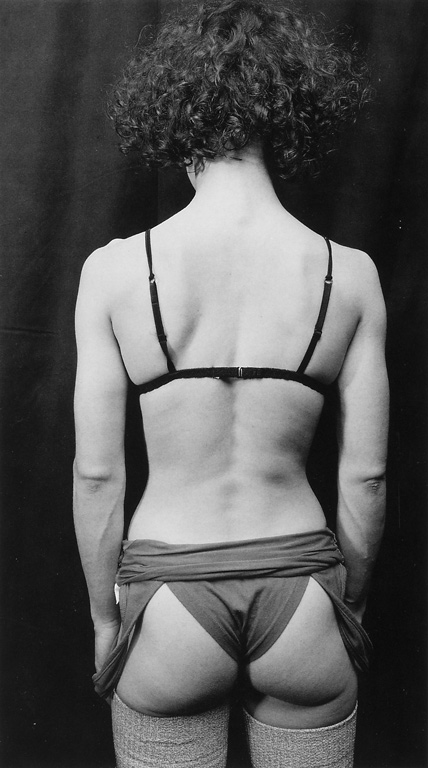

This was of the other girl who came from the country. She was very strong for a girl from all the work of farming and milking. She was very close to her family and to the cows on her father’s farm. She said that she could tell them all apart and that they all had names. She even said that one was called Marguerite but I think she said that to tease me and in any case, I didn’t care because your grandfather always called me Daisy. She was a very good worker but she came and went with the plantings and the harvests. Her brother would come and say she was needed and that was it. It was too unreliable to have a girl like that and eventually I told her not to bother coming back. She never stole but I had to tell your grandfather that she had because I gave her something that came down from his family. It was a painting of a field in France, of grasses and a haying. He never looked at it but she did when she was folding the laundry and I saw her one day and I knew she liked it. So I gave it to her when she left and told your grandfather that she had stolen it so that he would not be angry. It was very valuable and he wanted to go after the girl but I begged him not to make trouble and offered him a picture in its place. Every picture you see was an offering and he was very very grateful. I mounted the pictures in the album and we would sit together in the evening and look at them and talk about the girls just as you and I are doing now. That was how it was until he died.

She closed her eyes, seeming to drift off to sleep. Her head lolled against the back of the chair. He slipped the album from her lap and readjusted her bracelets. Six o’clock. He returned the album to the dresser drawer and pulled from the roll in his pocket four bills that he tucked in accordance with their protocol under the silver comb.

M. Beauchamp, I do not want you to come here any more.

He caught her reflection in the mirror, searched the dusky planes of her cheeks. Dry, and she was looking straight ahead, focused if at all on the tangle round her mirror of belts and costume jewelry. And she was calm. Calm as a girl in her twenties can be calm when she is bored or simply terrified. Expert now in her repertoire, she was using one last time the voice of the grandmother to veil her sadness at the loss of his money.

I cannot tell you this story any more. I cannot, not even for your pleasure. Find another Daisy, M. Beauchamp. I am not your Daisy any more.

George Steeves is an independent photographer living in Halifax. A major survey and catalogue of his work – George Steeves 1979-1993 – was produced by the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography in 1993. His projects have resulted in a number of solo exhibitions, including those held at VU, Québec City (1991), Galerie Vox, Montréal (1991), The Photographers Gallery, Saskatoon (1989) and Dazibao, Montréal (1983). Among his group exhibitions are The Tenth Dalhousie Drawing Exhibition, Halifax (1990) and Mirabile visu: The Imagemakers, Musée de la civilisation, Québec City (1989). His work is represented in major Canadian collections. In April 1995, Québec City’s VU will be presenting his series Equations.

Martha Langford was the founding Director and Chief Curator of the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography (1985-1994). Prior to the creation of the museum, she was Executive Producer of the Still Photography Division of the National Film board of Canada (1981-1985). She has organized more than fifty touring exhibitions and written numerous books, catalogues, articles and lectures on photography and museology. Now living in Montreal, she is completing research on a collection of photographic albums, toward a Ph.D. in Art History from McGill University. She is also a freelance curator and critic who recently joined Border Crossings as a contributing editor.