[Fall 1995]

by Pierre Dessureault

Associated curator, Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography, Ottawa

Since settling in Montreal on their arrival in Canada, Clara Gutsche and David Miller have worked together on many projects, producing a remarkable body of photographic work that portrays the city and its residents.

There are few examples of couples in photography who work together as a team. The Canadians Carole Condé and Karl Beveridge, and the German couple Bernd and Hilla Becher pool their visions and talents to work on ambitious ventures in which the individual is subsumed into the whole. The resulting works clearly bear the imprint of both contributors. Gutsche and Miller engage in a visual and intellectual dialogue that affirms their distinctive visions and their respective methods.

Their two joint projects on Milton Park and the Lachine Canal reveal, beneath the documentary surface, a shared belief in the power of images to explore social reality. The various groups of photographs, produced in parallel without any systematic exchange about subject matter or method, reveal a striking similarity in formal terms and in how they think about the visual arts.

From 1970 to 1973, Gutsche and Miller used photography to help save the neighbourhood of Milton Park, making images to preserve for posterity a multiethnic urban community whose configuration was changing radically.

Miller photographed the architectural heritage in great detail in all weather conditions, closely tracking its destruction. His views depict the complexity of an urban landscape in which a variety of styles, eras and natural elements coexist in total disarray. His document sheds light on the precariousness of this balancing act and on its gradual disappearance. Gutsche, on her part, explores the human side of Milton Park. Her portraits marry the personalities of the residents to their community. The subjects pose in a familiar setting, among the everyday objects that define their personal universe, impregnated with the collective values of their time. The photographer keeps her distance, remaining in the background and giving her subjects the limelight, respectfully portraying them in a social position.

Gutsche’s approach is developed further in Six Girls: An Extended Portrait (1974-1976). For three years, she painstakingly observed her neighbours, the Censic sisters. The closeness she was able to achieve opened a window onto the intimacy of a family and the rituals that punctuate the way women learn their social roles. From image to image, ritual to ritual, these adolescents blossom into self-reliant young women. In this narrative sequence, Gutsche goes beyond the social portrait, taking a feminist position that reveals how personal identity is created through interaction with a community.

Miller continued his exploration of architectural forms in two projects on the business district (1974-1979) and the Port of Montreal (1976-1979). In these, the documentary intent is combined with beautiful and unique architectural assemblages that are captured and enhanced by the photographic form. For Miller, a building is a monument imbued with a community’s values and history. Through photography, he defines the character of a place by delineating shapes, eliminating all superfluous details and going straight to the essence of his subject. In so doing, he brings out the harmony inherent in these assemblages and visually fixes them in time as part of the collective memory.

While the stated intent of the early period of Gutsche and Miller’s work was to closely describe social conditions and to record the visual configuration of things for posterity, the ventures that followed would take them separately towards increasingly personal approaches.

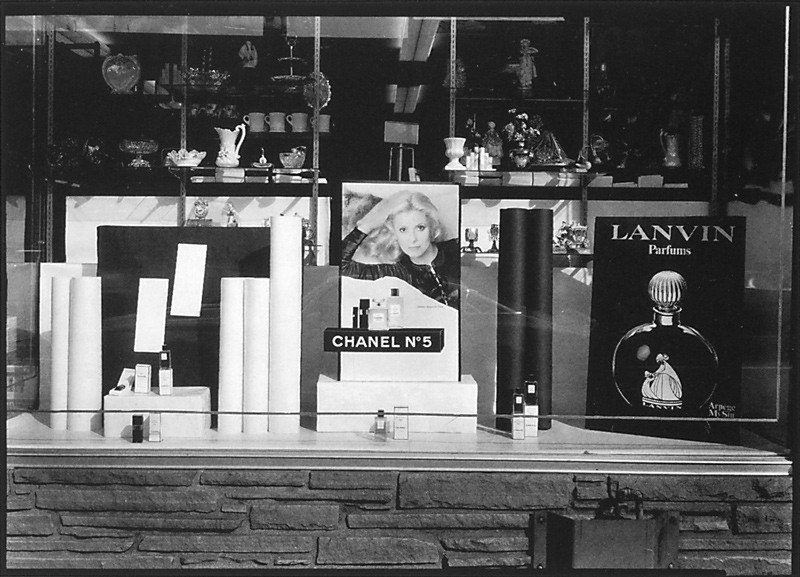

For Gutsche, the series Windows (1976 to 1980) was a clear shift towards the exploration of an inner world. The shop windows of small downtown Montreal enterprises become, in her photographs, screens displaying fantasies concocted by febrile marketing minds. In the space delineated by a window frame, objects are placed and related to other objects in an effort to delimit a theatrical space in which the game of full-contact consumerism can be played. The glass becomes a surface that sometimes reflects like a mirror and sometimes is transparent, like a doorway between two worlds. An imaginative play of projections, framing, accumulations and juxtapositions allows Gutsche to merge an outside world of products, words, posters, and an inner world of shadows and reflections, seduction, and desire. Each window becomes a heterogeneous kingdom ruled by a demiurge pulling the strings behind the scenes. Each image opens onto a dreamlike universe with its own laws.

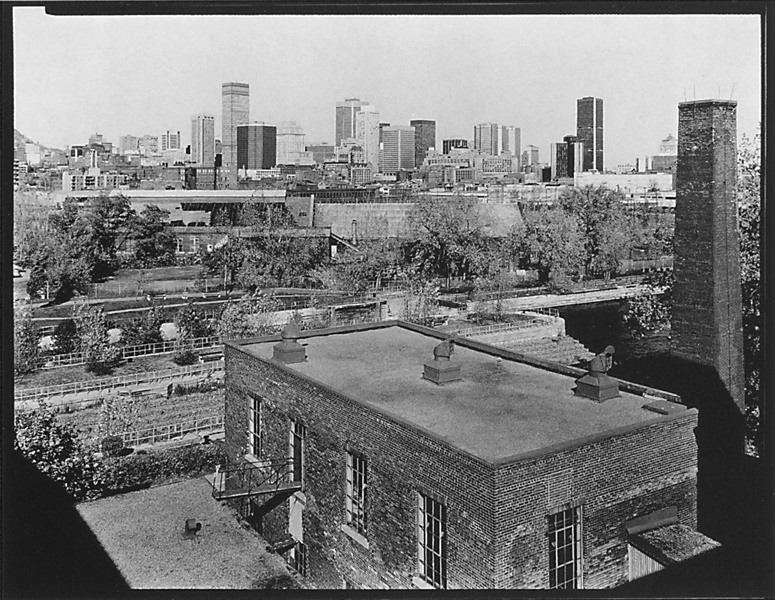

As Miller progresses in his study of Montreal architecture, he appears to recall the nineteeth-century association of photography with urban development. His series of construction site and parking lot photographs (1980-83) evokes the distance and objectivity of the work of the British photographer Delamotte, Marville from France, or the Canadian Notman, who attempted to celebrate the march of progress and civic pride. Miller’s work gives us a topography of contemporary urban chaos. Like Gutsche’s windows, his prints display a rich visual dissonance by projecting and framing discordant layers, accumulating and juxtaposing disparate elements. His lens scours the cacophony of forms in a city abandoned to greedy developers more interested in big money than civic pride. In 1985-86, Gutsche and Miller together completed a commission on the Lachine Canal from the Canadian Centre for Architecture. They divided the work to suit their personal interests: he took on the exteriors and she concentrated on the interiors. Miller gave free rein to his fascination for the remains of the landscape inherited from the industrial revolution. The precision and rigour of his descriptions, combined with the complexity of the information, yield tiered views, with a sequence of images cascaded all the way to a blocked horizon where the levels of history melt into a vast, undifferentiated whole. The density and contrast of his prints translate this thick urban landscape into a geometric space where successive shapes and disparate materials intermingle.

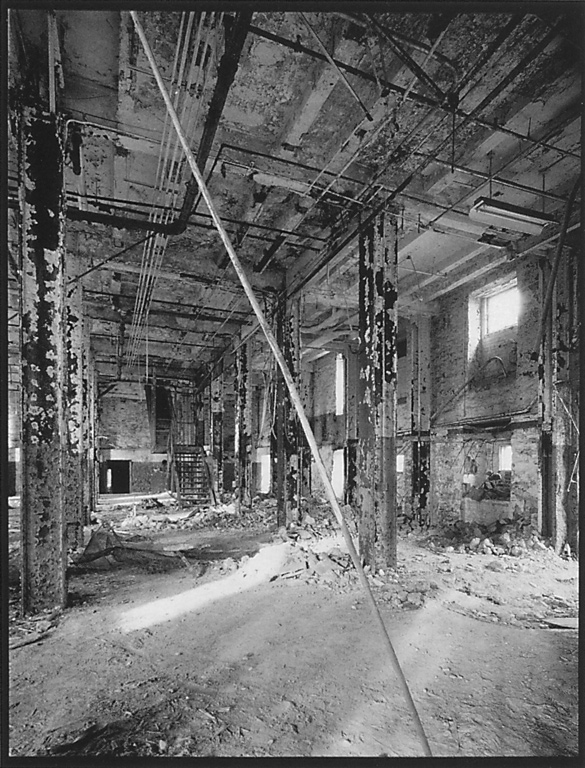

Just as Miller’s buildings appear as solid and compact monuments, Gutsche’s interiors translate an inner space with fluid contours. In these deserted factories, Gutsche assembles evidence of human passage: rolls of paper unravelled on the floor, dismembered dummies abandoned in a corner, a stepladder standing in the middle of a room. For her, these constructs are merely empty shells haunted by the absence of those who once inhabited them and busied themselves there. As in the dreamlike theatre of the store windows, here too the boundaries between interior and exterior are erased: walls, whose function is to separate spaces, are pierced by large windows spilling cascades of light to delimit these abandoned sites. The final act of a tragedy— the disappearance of what in the last century was prosperity incarnate— is played out in this theatre of objects.

The portraits produced independently by Gutsche and Miller over the past few years illustrate the unbridgeable difference in their approaches.

From 1983 to 1988, Gutsche took portraits of her daughter Sarah. At the outset, she placed her in an intimate setting. As the years go by, the mother watches her daughter grow, observes her friendships, and examines the unbreakable ties that bind them. Gutsche translates this intimacy into a visual vocabulary of marked contrasts, using cropping to locate the subjects within their own environment and poses that reveal their attitudes. The feminism that was beginning to appear in Milton Park and Six Girls can also be seen in this chronicle: girls learning the feminine roles. Milton Park placed these rites in a social context. Six Girls studied these passages in a family setting. Here, Gutsche restricts her world to the home, focussing on Sarah and her best friend Noémi: the resulting portrait blends affection and affirmation.

Just as Miller’s architectural views superimposed planes to reconstruct the whole urban landscape, his portraits focus on facial architecture, the set of traits that determine how a person looks, where the inner structure of the edifice constantly comes to the surface. Miller’s visual vocabulary goes hand in glove with his approach. His closeups eliminate spatial and temporal reference points, and the diffuse lighting removes any dramatic effects from the facial features. Miller never looks for psychological traits in the subject’s personality, nor for an expression that might reveal states of mind. His portraits are neutral, clear, and precise, but they are filled by the subject’s presence. A portrait is a face upon which the subject’s inner strength is etched.

For more than two decades now, Gutsche and Miller have produced significant works that illustrate their consensus on the representative power of photography, the timelessness of images, the specificity of the medium and the materials it uses, and the complementarity of subjects. This uninterrupted dialogue has helped them to develop complementary personal visions that are further enhanced by the individuality and originality of each photographer.