[Spring 1996]

by Suzie Larivée

The garden is an image of the world

San for the mountain. Sui for water.

The sand becomes water. The stone becomes a mountain.

The Japanese garden is a theatre: in transposing a landscape, reducing an existing natural site, it brings together an ancient arrangement of water, stones, sand, hilly islands. The Japanese garden, like all gardens designed by human beings, is intended to be an image of the world.

Frank Michel brought back from a long stay in Japan a series of photographs of gardens he visited in various cities. Sansui. San for the mountain. Sui for the water. These words, for Westerners, belong to the vocabulary of travel. In a way, Sansui represents a list, an inventory, of places visited, a collection of images that document territories, eras, creators. It is a census, an exploration of these constructed landscapes with hundreds of years of history and a symbolism that is beyond our cultural references.

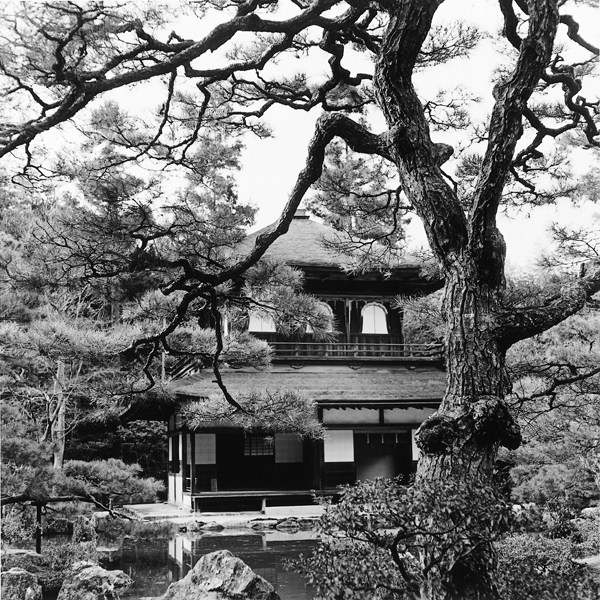

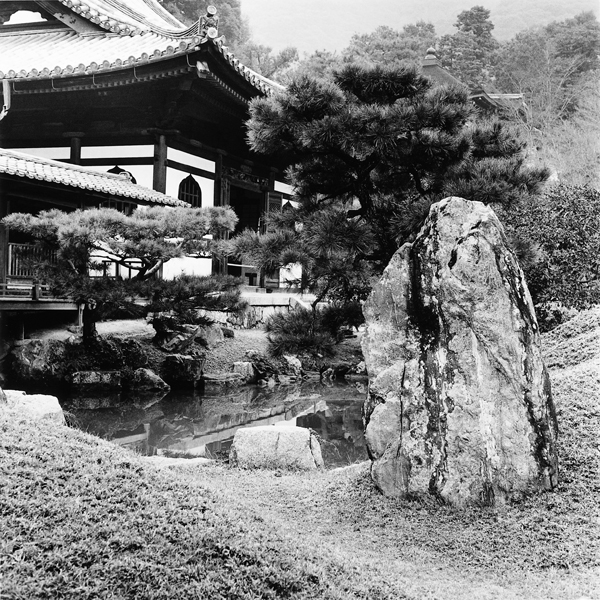

The Japanese garden is a reserved space, often in a very limited area, but imbued with a complexity of detail, sculpted by shadow and light. The photographs in the Sansui series show us two types of Zen gardens: the walking garden and the dry garden. The walking garden is crisscrossed with twisting paths that not only lead the walker from one place to another but, especially, constantly renew the point of view. The dry garden, very spare, is made of stone, sand, and gravel, bordered with indeciduous trees. These components give it a sense of immutability. The dry garden is not to be walked in, but to be observed. Like a quotation, each stone placed on the sand represents a mountain millennia old and reinvents a landscape replete with history and legends.

Franck Michel’s images combine two approaches to the photographic process. The approach of working with landscape issues from a tradition that says that photography is, above all, “a particular view of the world,”1 an act of attention, gathering, and contemplation seeking to provide the maximum of information on the state and ambience of the site. Here, the desire to assemble points of view as evidence of a journey made through Japanese gardens, to allow images to emerge as one travels, without any intervention except the click of the camera, recalls a comment by Pierre de Fenoyl: “The photographer does not create, but looks at Creation… which is Time.”2

A second approach, which defines the photographic act as an act of arranging, constructing, intervening in – even inventing – the real, is also reflected in the Sansui project. Michel proposes a very personal vision of the Zen garden, organized around framings of the landscape, montages of elements of a state of nature imagined and constructed by human intervention. The components of the Zen garden, already composed to create a theatricalization of nature, are represented in an intimate mode, privileging certain “moments” of the visit. The photograph is a “viewed presence of things.”3 The garden is an image of the world…

At the last Mois de la Photo à Montréal, Franck Michel presented the exhibition Les Frontìères de l’ombre, Aspects de la photographie contemporaine japonaise/The Frontiers of Shadow: Aspects of Contemporary Japanese Photography. Currently, he is preparing an exhibition of his own photographs of Japanese gardens.

1 Régis Durand, Le Regard pensif, Paris, La Différence, 1990, p. 60.

2 Pierre de Fenoyl, La Chronologie ou l’art du temps, exhibition catalogue, Bibliothèque Nationale de Paris, 1985. Cité dans/quoted in Régis Durand, Le Regard pensif.

3 Roland Barthes, quoted by Régis Durand Le Regard pensif.