[Spring 1996]

Galerie Vox, Montreal

January 11–February 11, 1996

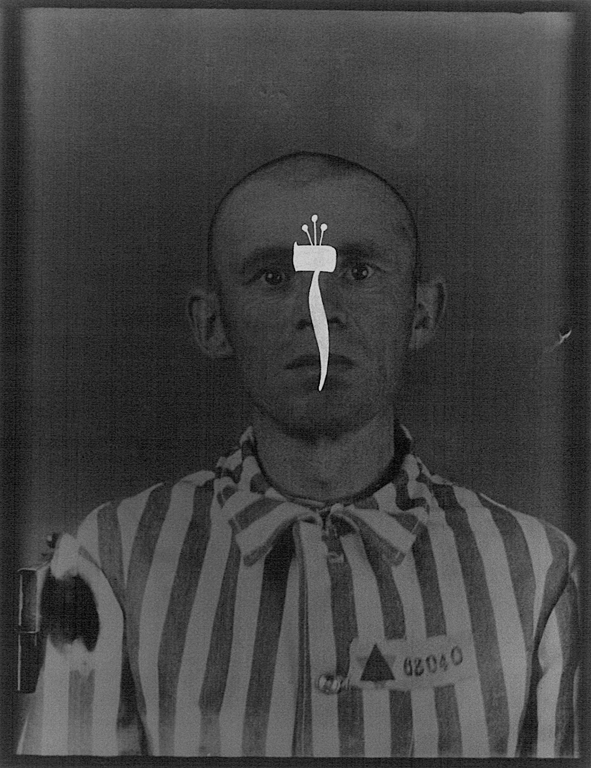

With his recent exhibition Yahweh!, Toronto-based photographer Simon Glass virtually transforms the rather small and narrow space of Galerie Vox into a shrine bringing to mind, of course, the perennial analogy between museums and cathedrals or, in this case, between gallery and temple. Four different groups of silver prints, combining photographic images and Hebrew text, propose to address the broader topics of religion, Creation, and history by conjuring up a dialogue between the mysticism of Jewish theology and the systematic horror of the Holocaust.

Previously known for his subversive nude self-portraits seeking to challenge the very origin of dominant notions of masculinity and femininity, Glass pursues his interest in the body as metaphor for systems of belief. However, with his blatant use of heavily connoted imagery borrowed from concentration camps, the apparent “universal” quality inherent in his earlier work is rapidly obscured. The pointedness and specificity of these emotionally charged references – their historical, political, and ideological setting – tends to disengage the viewer from his or her attempt to reconstruct any artistic process. Once a document, always a document? Perhaps not, but in this case, the archival element clearly outweighs the work of art.

Rather than instating the aspired insight into more general and open trains of thought, Glass’s able formal and plastic interventions – gold leafing the prints’ surfaces and turning the skin textures of their central motifs into sacred alphabet (Book of Formation); superimposing gold letters or burning in white ones on human faces and bodies (Golem I, Golem II, Yahweh, Merciful and Gracious); aligning the images vertically to create the effect of a column or monument (Yahweh); anachronistically adding a bar code to one of the all-too-registered Nazi-signed “portraits” of Auschwitz prisoners (Merciful and Gracious) – serve instead to comment artistically (decoratively for those of us who do not read Hebrew) on a historical citation, whatever that really means.

In short, what the exhibition Yahweh! has to offer is more along the lines of technically accomplished aesthetic objects that convey, on the one hand, spiritual rhetoric; on the other, unnerving memorabilia of historical reality. And nowhere do their paths meet, at least not as art.