[Fall 1996]

Clément’s technique as an artist does not differ from his technique as a reporter-photographer, which he is as well. But it is absolutely enough to “bring the earth closer and establish a world,” to take up Martin Heidegger’s fundamental thought.

“Bring the earth closer” means bringing to the surface that which is in itself strange, opaque, and hidden, to the point that it is clear to us. “Establish a world” means making things permeable to humans, instilling a vision of the world in which we can live and think. In this, Clément is an artist, and for this, to Clément, photography suffices.

by Jean-Claude Lemagny

Through the current trends in creative photography run two opposing movements. The first is a photography turned upon itself, seeking a deeper examination of its own nature and an exploration of the extent of its expressive possibilities.

The second is turned outward, toward encounter with other visual arts for mutual enrichment and fecund cross-fertilization. It is the latter movement that is presently in favour with critics. However, although I do not dismiss it entirely, I do not see myself in this current.

To clarify matters, it should be noted that manipulation of the print, the use of non-silvered sensitive surfaces such as bichromatic gum, or production of large-format prints are practices faithful to pure photographic technique and do not presuppose any contamination. They are obtained by means specific to photography. In fact, history is full of examples of the influence of some arts on others, and this has never justified the abandonment of the unique nature of any of them.

We could extend the debate beyond simple technical considerations, by taking into consideration some artists’ intentions – such as adapting their work to museum spaces or situating it within the general trends in modern art (for example, abstract art or surrealism). These might be legitimate aesthetic ambitions, which could very well accommodate themselves to the purity of the medium, or they might comprise a desire for success and social climbing that has absolutely nothing to do with artistic concerns.

The fact remains that there are numerous examples of mixing media, such as painting on a photograph or combining photography and drawing. Such procedures may give rise to masterpieces (such as Rauschenberg’s paintings), but they pose the problem of divining in each instance whether the photographic medium itself is still being examined or whether it is simply being “used” (as a number of critics have naïvely admitted). Indeed, if it is being “used,” it is present no longer as art, but as a means, and it is thus placed outside of art and no longer preoccupies those who are concerned with photography as art – for art is a fundament and cannot be submitted to any utility.

Mixed or not, technique is the only problem faced by any artist worthy of the name, given that he or she considers that it must be examined.

Serge Clément’s works seem to have little to do with such general speculations. They are unequivocally, purely, directly photographic. But if I introduced my subject so obliquely, it is because this work seems to me to be the exemplar of the strongest and most fertile pole of current photography: the exploration of photography through photography, and an economic use of means to seek profundity, not transgression. A certain rigour in his style keeps him from seeking vision elsewhere and makes him spontaneously suspicious of a sweeping error in art these days: that of hoping to resolve a problem by getting out of it. Art has in common with science that no valuable result will arise without a precise definition of the problem under consideration. And this is above all a condition vital to the imagination.

Clément’s technique as an artist does not differ from his technique as a reporter-photographer, which he is as well. But it is absolutely enough to “bring the earth closer and establish a world,” to take up Martin Heidegger’s fundamental thought. “Bring the earth closer” means bringing to the surface that which is in itself strange, opaque, and hidden, to the point that it is clear to us. “Establish a world” means making things permeable to humans, instilling a vision of the world in which we can live and think. In this, Clément is an artist, and for this, to Clément, photography suffices.

His work is typical of a path through and to photography that rejects the spurious approaches in which so many major photographers find themselves mired today. To become involved, Clément had to go far beyond the archaisms and timidity that might lead one to believe that photography is utterly unadventurous.

In my opinion, direct photography long had a tendency to confuse problems of composition (framing) and of ambient poetry – for example, Cartier-Bresson and Moholy Nagy on the one hand, the pictoralists and Joseph Sudel on the other. Of course, these are qualities that do not fade away and that are still found, in various proportions, in beautiful works.

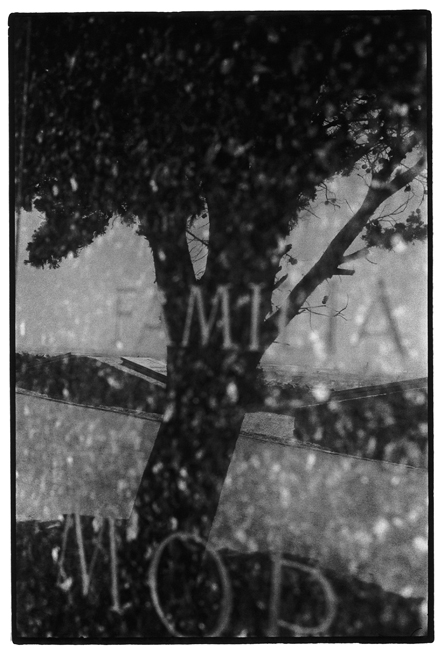

To a Serge Clément, there is something else. For him, the space of the image is not thought of above all as an assemblage of elements in a certain balanced order, nor as an evocation that draws the viewer into a dream. The space of the image is felt as a continuous field of more or less thickness or thinness, opacity or transparency, swellings and concavities, visual softness or roughness of a component milieu of photography, made of ripples in a more or less sombre subject matter. It is against this sensitive, original background that the realities that are the proportions between the parts and the supports for the imagination mingle.

This area of constraints and difficulties is, for this very reason, a space of liberty and open possibilities. It is an accepted path that goes from appearance to presence.

It is the sudden, incidental, unexpected appearance of that which arises before the eye or the camera viewfinder. But while the reporter, as a professional, wants only to set a document, freeze a memory, Serge Clément the artist first frames an instant lived in poetry, a vision through which, suddenly, the entire world is imbued with a certain ambience, a truth that precedes the thought of it, an image to which we will want to return since it takes us back to a unique reality.

Presence: Because appearance can keep its specific quality only if it finds its true incarnation in an objective material, that of the photographic proof, which splits the experienced instant between a memory of something that no longer belongs to anything but the past and death, and a continued presence where the imaginary will always be able to return to its roots. By reiterating itself in the print, the photographic operation allows us to reconstruct, though not without effort, a reality that will be sufficient unto itself.

Clément shows us how to forget what is, to remind us of what is seen. And within this passage, not before, dreams can be born – not in ruminations on meaning, but in a communion with the senses. For in the presence, the quality of the appearance must be maintained.

Thus, the most ordinary things can be reconstructed in the world, revealing surprising layers of reality, depths that are reflected within the presence.

In suspension in the dark crystal of a reflection, a tree, an entire scene, appear within the polished granite of a tombstone; when they are smooth, objects also take photographs every moment, all around us. They bring us images of a sleeping world in the hard shine of stones and metals. For the photographer with an attentive eye, these ephemeral, dreaming colleagues reveal that the world exists in many more versions than we acknowledge and is composed more of mirages than of realities.

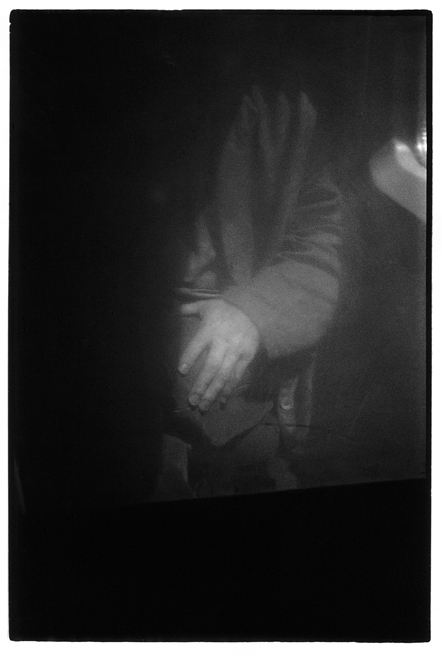

If stone can harbour the clarity of scenery, shadows can give rise to beings – at least in photographic poetry. The hand that emerges from the shadow is something that no longer escapes the rarefaction of light; poetically, it merges like a fertile plasma from the depths in which mysterious germinations take place.

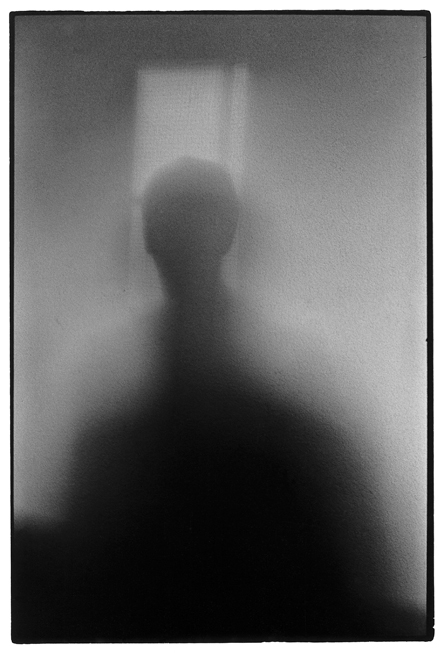

The man who seems to be seeking himself in his own shadow, reminds us that in photography bodies are never born except from the condensation of greys. His uncertain silhouette has more presence than many detailed characters since it participates directly in the material of which it is made.

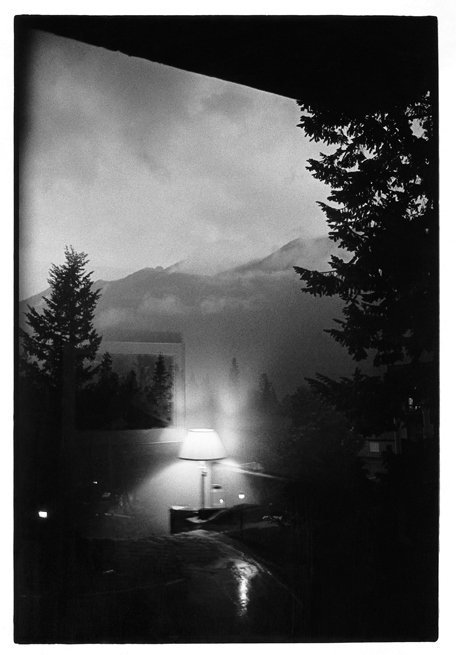

If here the shadow finds a sort of biological existence and the depth that belongs to humus and ocean deeps, light, for its part, acquires an independent life and living consistency. The clarity seems to radiate like an autonomous being that, like a glowworm, glimmers with internal strength, as in the luminous door that twists on itself and trembles under the effect of its own energy.

Reduced, bouncing, crackling, the light, often so soft, sometimes becomes a fire that devours all and destroys through its excess that which it usually reveals.

From depths as black as those of still water to blazing whites as nervous and vibrant as electricity, Serge Clément’s images exist according to a poetic truth that extends and spreads in parallel to recognized, sensible, conventional reality. In them is demonstrated the truth that Nietzsche teaches us: that in art the lie becomes positive and one cannot help but pass through it to reach the truth. If we stop and think about it, this is borne out in and by photography, which is so often squeezed into a prosaic, unresonant objectivity. With Clément, the art of light opens an immense space of poetry and transfiguration where things and simple beings of the world come to blossom like mysterious apparations and live like obsessive presences.

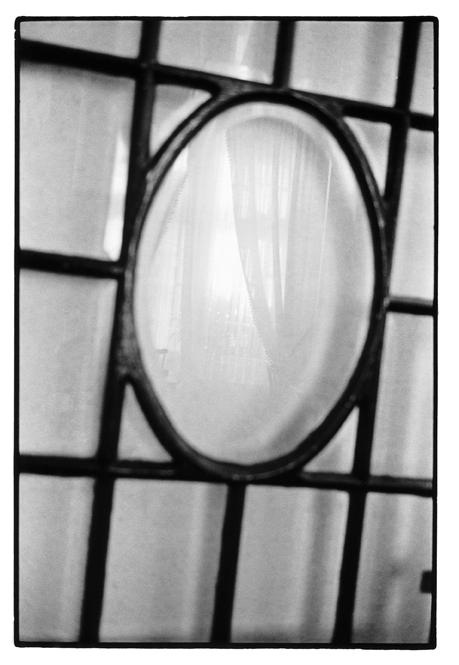

Both translucid pane and inhabited mirror, the milky-white oval could symbolize photography, which both welcomes and transfigures and which, when it assumes the precise frame of art, takes things and beings from appearance to presence.

Serge Clément lives and works in Montreal. He is very active on the Quebec and Canadian photography scenes, and his works are exhibited regularly here andabroad. Since publication of his book, Cité Fragile, and the retrospective organized by Le Mois de la Photo à Montréal in 1993, he has continued to refine his poetic regard on places, things, and people. The Jane CorkinGallery in Toronto will present the first version of hisproject Vertige-Vestige in early autumn, 1996.