[Fall 1996]

Centre international d’art contemporain de Montréal

May 2–July 28, 1996

From Homer’s Odyssey to Kerouac’s On the Road and beyond, travel has provided inspiration for countless tales. Part of the attraction lies in breaking boundaries, in widening the realm of the imaginary. Then there is what Voltaire’s nomadic characters Candide and Cacambo recognized as the particularly gratifying experience of distinctiveness while recounting the sights of one’s voyages. The advent of photography, with its claim to veracity, was to give new impetus to the desire for mirrored (and tacitly appropriated) images from distant places. Although distances have been increasingly reduced, modern means of transportation and communication have not yet managed entirely to eliminate the somewhat liberating sensation of novelty when exposed to unfamiliar lands and cultures.

Organized by Pierre Dessureault of the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography, the exhibition Travel Journals, featuring the works of nine Canadian photographers, was presented in part last summer at Montreal’s Centre international d’art contemporain. Close to sixty images by Richard Baillargeon, Robert Bourdeau, Geoffrey James, and Ian Paterson, dating from 1978 to 1992, challenge to varying degrees the conventional approach to the most long-standing tradition of their discipline: travel photography.

These artists’ images have less to do with a positivist or so-called objective translation of reality than with the photographic accuracy of their own subjective outlook when encountering the places to which they have traveled. While Baillargeon’s colour and formally articulated diptychs of Egypt, annotated with fleeting descriptions of sites unseen in his photographs, could be compared to a clever exercise in style, Bourdeau’s gold-toned prints of architecture and monuments, generally shot at close range in Sri Lanka, Spain, Mexico, and southern France, are quite plainly about surface, texture, and, one could surmise, cultural erosion.

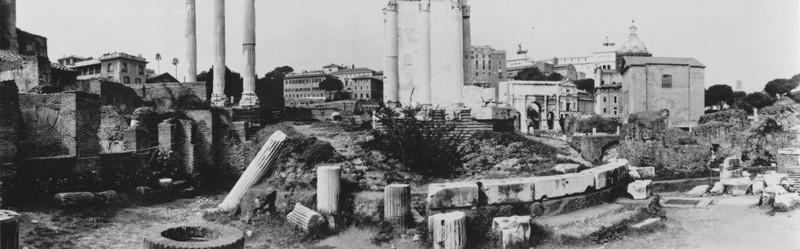

With the exception of the romantic, at times symbolist, haze that he purposely integrates into his black-and-white compositions of French gardens, Paterson appears to take a back-seat approach to his subject matter. As a result, his images, for the most part, have a rather anonymous air about them. James provides the most engaging images of this otherwise all too impassive exhibition. Although indisputably classical were it not for their unnecessary enlargement, his black-and-white panoramic views of Roman sites subtly stress the dissonance between past and present civilizations, between the reminiscence of order and the reality of chaos.