[Été 1997]

by Juliet Hotbridge

Still confused with the good and the beautiful, in spite of centuries of philosophical reflections, the truth has the strength of evidence before which humankind bows respectfully, while the false carries the stigmata of its bad reputation and embodies blackness and corruption to the point of being assimilated into absolute evil. However, it is precisely appearance that enables reality to manifest itself, and artifice that gives meaning to the truth. History and experience constantly remind us that what has the face of truth and is revered as such can, from one day to the next, “prove itself” false and send the most beautiful theories tumbling, throwing us into the chaos of uncertainty.

It is more difficult to recognize that, conversely, the false possesses intrinsically the versatile capacity to mutate itself into the true at the first opportunity.

Art is a privileged territory: in it, dream, allegory, mask, metaphor, illusion, and fiction benefit from the greatest possible freedom. Like Dieu trompeur, art enjoys appearing in spaces, at times, and in forms in which it is not expected, as a great strategist of mystery and surprise effects when we are to be seduced or shocked, not with the intention of concealing, but to remind us of its true nature.

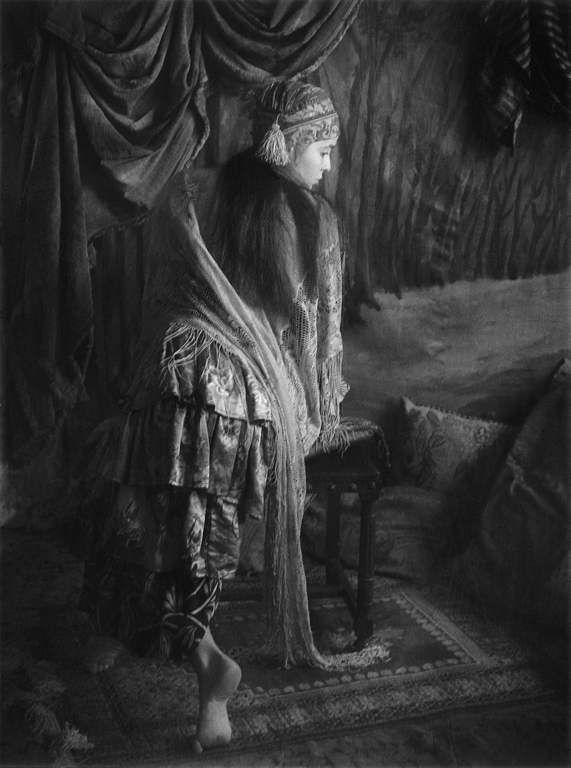

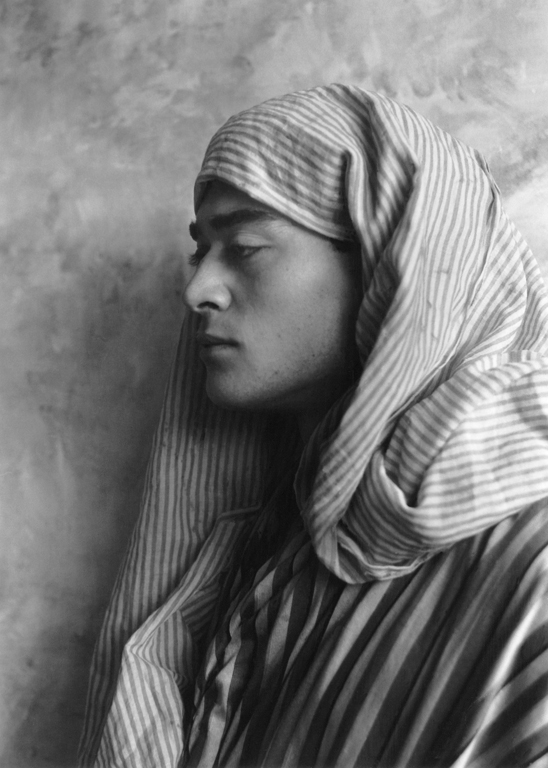

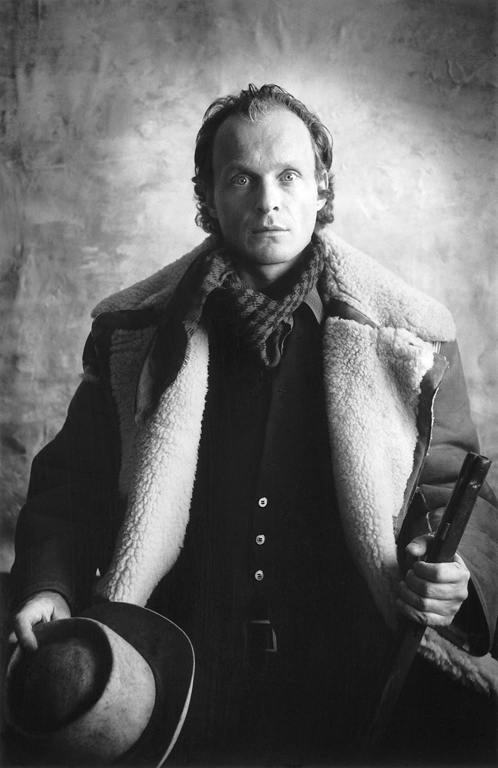

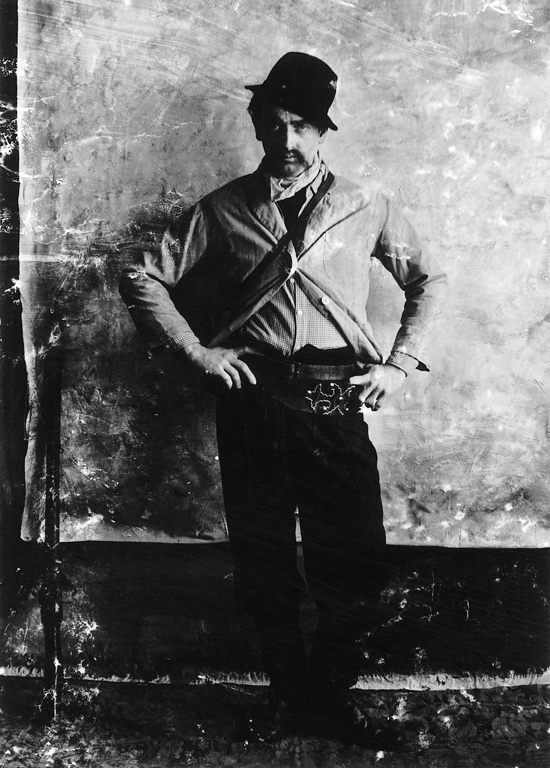

True amateurs will not see the Albums of P.M. Hoblargan merely as a hoax, nor will it occur to them to treat the artists as forgers; rather, they will be struck by the authenticity of the artists’ commitment, their choice to relive the unfolding of another era in the “past conditional,” assembling above a single signature the entire visual and aesthetic evolution of photography from the nineteenth century to the nineteen-twenties, the merging of stylistic features of different photographers revisited becoming the source of their own autonomy.

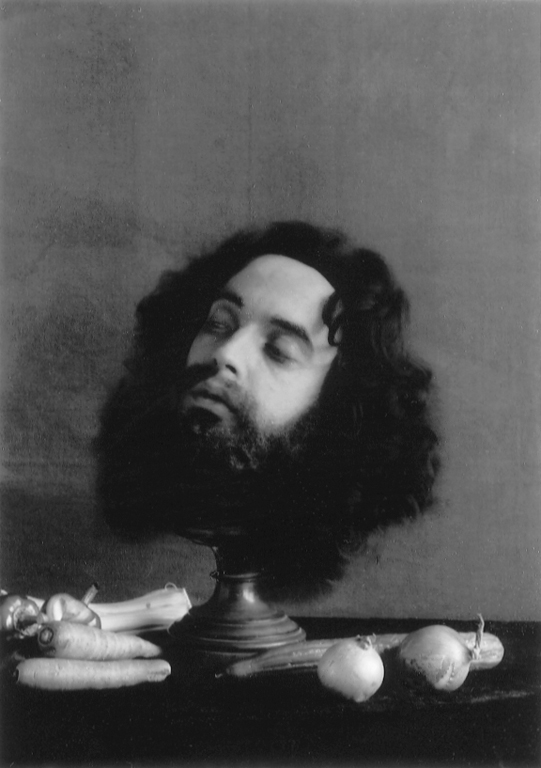

Beyond simple tribute, and without ever falling into caricature or mannerism, the work of Hogan and Amblard is stamped with the sense of the natural, the freedom that proves they are more interested in investing in a past than appropriating its effects and representations. Far from setting a trap for us, they are the ones who have slipped into this bygone era whose aura fascinated them. If, through them, we believe as well, it is only fair, since this world, re-created by bits of fabric, a few objects, and the marvels of imagination, embodies their truth.

Their interpretation extracts the essence of that century, as if it were a perfume that does not attain its ultimate fragrance until after a long period of maturation, and whose most exquisite scents, withheld until then, are finally revealed.

If there is a trap, the only ones who fall into it are those who place their vanity as “connoisseurs” above art, and the loss of sacrosanct historical references leaves them unable to deal with the profusion of images from nowhere and everywhere at the same time. And worse, if they are curators, merchants, or collectors, they have been confused by photographs that, in contempt for the “serious” market, present the unpardonable error of not existing (and for good reason) except as modern prints from 1988 and 1990.

Others would seek no further than the pleasure of appreciating the artistic quality of images and the stunning mastery of this unknown, suddenly discovered photographer. Some – just a few (twelve during the forty days of exhibition of Premier album 1855–1923 at Galerie Michèle Chomette in Paris in 1988) – understood the sleight of hand that was being presented; hunting down anachronistic details, they exclaimed, “This horse is not from the nineteenth century!” or “This gun didn’t exist in Texas in 1900!” But beyond this jubilant game of “find the error,” they recognized the true value of the works exhibited, without making intention an issue: the share of resurrection of the past, embodied in the fictitious character of P.M. Hoblargan, and that of the free creativity of the real Hogan & Amblard – even though they were made outside of the advertised time frame.

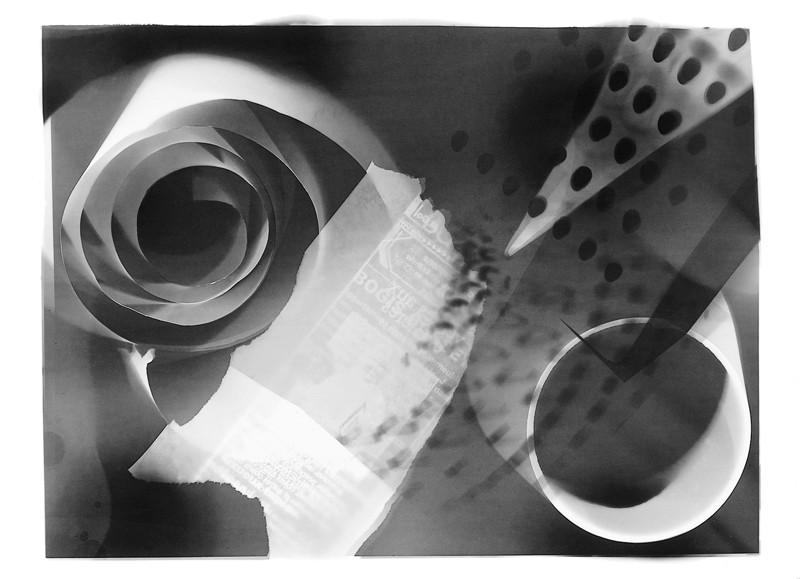

Bringing together the archetypes of genre photography – primitive, pictorialist, and finally modern, from the portrait to the composition, via the architectural view, the landscape, the still-life, the nude – the duo of photographer-models (since most of the time they are their own models, barely recognizable from one image to another and impossible to recognize in their photographs) vary the portrayal – the figuration – to infinity, travelling while rarely leaving the studio, and, as an authentic, unique man and woman, giving birth to hundreds of other people, all of them different. From Voyage en Italie to Orientalist exploration, from an excursion to the country for “landscape painting” (since Switzerland, where they live, also has its Barbizons) to the luminous statements of the urban “new modernity” and the true beauty of things, the recurrent themes that they address with a spontaneous mastery find their sources not only in old photography but in the painting, literature, theatre, even cinema, of bygone times. P.M. Hoblargan lived a long time, until 1923, and his travelling curiosity took him both to Hollywood and to Berlin, where he was able to capture the famous chiaroscuro-on-tortured-face of German expressionism.

Unique and multiple, like the rose of Saint-Exupéry’s Little Prince, the Hoblargan experience is read and lived differently by each individual. By situating themselves outside of time as did the artists, viewers of these scenographies will discover, like Epicurus, the accidental nature of time and, like da Vinci, that artistic activity is first a cosa mentale, whatever relationship to the real world the photograph implies.

P. M. HOBLARGAN

Melissa Hogan an American by birth, studied photography in the southern United States . She lives in Geneva, where she works as a photographer and painter. Patrick Amblard was born in France and now lives in Geneva. He began his artistic career as a painter, although he was interested in photography. In 1986, Hogan and Amblard began a photographic collaboration, while pursuing separate careers as painters. They have produced two series together: Les albums de P.M. Hoblargan 1855–1923 (1987–90) and Meurtres au musée (1992–93).

Juliet Hotbridge was born in 1974. She lives Paris. A university student, she is writing a thesis on paradoxical reality in film and has a column on a culture radio programme.