[Winter 1997-1998]

by Gary Michael Dault

She wanders the streets of twilight cities, Jocelyne Alloucherie tells me, Montreal and her native Quebec City, yes, and also the early-evening cities of Europe.

She wanders, flâneuse, with a camera, exploring, as the cities turn haptic in the diminishing light and thickening darkness, the absorbing demineralization of a city’s architecture, ruminating with a camera upon the ways in which mass, volume, plane, and edge can be transformed from sublunary states of boundary and accumulation (all enclosed within what Alloucherie calls – albeit in a slightly different context – a “narcissistic perimeter”) to vitally fragile, generatively ambiguous sites for interpretation of the artist’s (viewer’s) selfhood and architecture’s dense and centripetal heart. In the course of a prose epic-in-progress titled On the Nomad Gaze, Alloucherie points out that she is especially engaged by those qualities of the locus of artistic territory that are generated “at the point of encounter, where territory overflows, surges forth, where it withdraws and drowns. When it plays and imperils itself, when it is exchanged in the displacement and beating of its borders.”

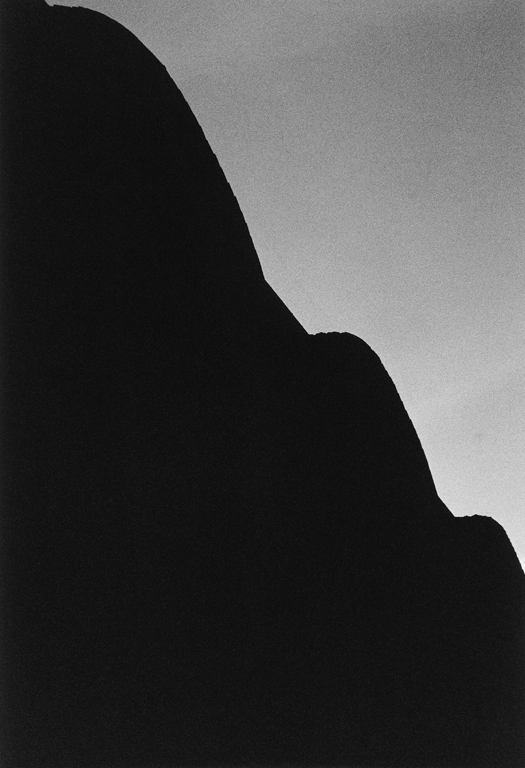

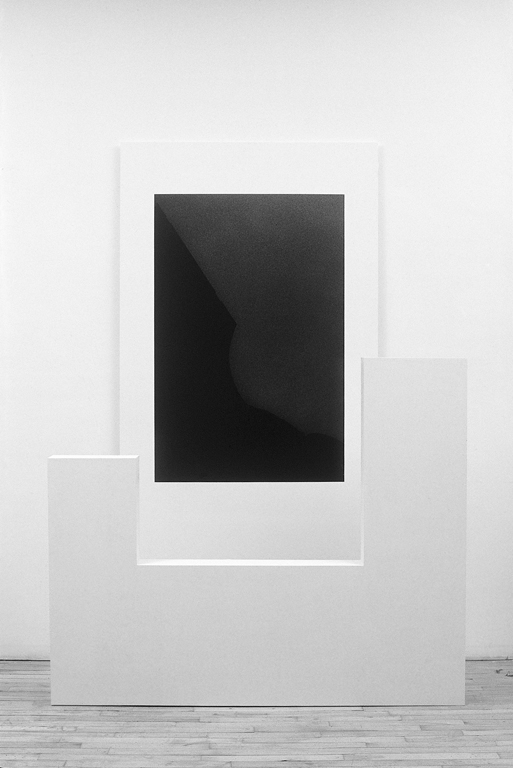

The exquisite photographs gathered here are images – vague images, Alloucherie calls them – of “historic or powerful places,” all of which are ultimately to be sequenced, along with further images, into a forthcoming work in which a majestic procession of these large (36″ by 50″) vertical photographs will attend and provide an eloquent kind of commentary or gloss for or attenuation/elaboration of a vast, eventual block of white plaster – a dense utterance of ur-architecture, or, as Alloucherie puts it, “an architecture which refers to an inner architecture.” Good buildings have always seemed to me to be a sort of structural exhalation; Alloucherie’s massive plaster emplacement will be the opposite – a kind of architectural sucking in of the breath, an architectural “white hole.”

These photographs are remarkable on many fronts, not the least significant of which is the way they bedevil and transcend the figure–ground impasse whereby the built structure takes its conventionalized, authoritative place against the inchoate nonsupport of an unexplorable and therefore limitless ground. The “subject” of these photographs is not the sibilant or sawblade edge of a dark building stark against a still luminous sky, but the tempering, like steel in fire, of the one element at the behest of the other (Jacob wrestling the angel, where the angel is ground). In these photographs, no one matrix bests the other, nothing comes out on top. Even though the dark architectural passages sweeping across the paper sometimes, almost, betray events (a rind of edge, a rasp of flange), and even though the brighter passages of firmament sometimes, almost, betray conditions (a sigh of bright cloud, a glimmer of reflection), neither is privileged to the point where the photograph as a whole falls into time, becoming a kind of stage set upon which two kinds of mutability can be pointlessly (one wants to say even lasciviously or carnivorously) compared. What would become of that but an empty ubi sunt sentimentality?

Alloucherie says she walks around her cities at the end of the day. “Very nomad,” she tells me. Alloucherie moves and her twilight cities move back. (“The gaze of art,” she writes, “is essentially nomadic.”) Note that it is not the photographer who is nomadic, but her engulfing gaze, her travelling attentiveness. This shifting, crossing, doubling, rootlessness of the photographer’s gaze (all of our gazes) results in – try to be patient with the paradox – a fixed linearity of vision. That is, just as the photographer’s gaze moves, floats, circulates (vision is like a flowing river of revitalizing vitality, like an outward echo of the fluid circulations within our bodies) and takes in a great deal of visual territory, so it is, at the same time, fixed within the perambulating given of the photographer’s attentive body.

That is why the photographs sometimes seem oddly long and valiantly uncomposed: they are points of concentration joined smoothly together, many focusings along a line and over a field. And so, these paradox-rich photographs move and are still. They are sharp and pointed, but without a centre. They are epistemological emblems of the way we really see – as opposed to the way we think we see or would like to see. “Being moves,” Alloucherie writes. And that is the fount of their strangeness – and of their disturbing familiarity.

Jocelyne Alloucherie has been an important figure in Quebec contemporary art for a number of years, and her works are exhibited regularly both nationally and internationally. Among her recent exhibitions have been a solo show at Galerie Claudia Delanke (Bremen, Germany) and at the Nova Scotia Art Gallery; coming up are shows at the Canadian Museum of Contemprary Photography and Galeria The Box (Turin, Italy). In 1997, Alloucherie received a DAAD (Deutsch Academysh Austaus Dienst) grant. Some of the works presented here were in an exhibition at Galerie Samuel Lallouz (Montreal) in autumn, 1997.

Toronto-based writer and art critic Gary Michael Dault is an Adjunct Associate Professor at the School of Architecture in the University of Toronto. He is the author, most recently, of Flying Fish and Other Poems (Exile, 1996), and is the Editor of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada’s Architecture Canada 1997: The Governor General’s Awards for Architecture.