[Spring 2000]

by Gary Michael Dault

Power Plant, Toronto

from December 11, 1999, to February 20, 2000.

Given the scope and ambition of the two photo-works that Angela Grauerholz presented recently at Toronto’s Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery (which extend the inventiveness of her photo-installations for Documenta IX and the 1995 Carnegie International), it is clear that the Montreal-based photographer is intent upon solidifying and expanding her examination of the role that photography can play in the highly directed act of codified looking – especially as that act is generated by the museological experience.

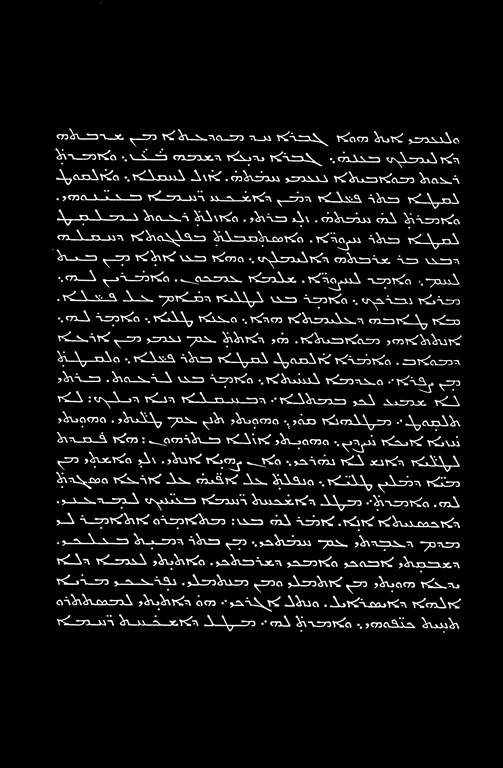

In Schriftbilder (1999), Grauerholz shows a series of severe black-and-white photographs of text samples (aphorisms, fragments) from a number of historically remote and thus exotic languages (Babylonian, Syriac, Mandaean, Cypriote, and so on). These are harvested, as Power Plant director Marc Meyer points out, “as 19th-century transcriptions made for l’Imprimerie Nationale de France,” a fact that “explains their incongruous homogeneity; the artefacts of many cultures, they have been processed to suit the purposes of one society, only to be distilled further until they have become empty metaphorical vessels for use by a single artist.” Because these handsome, inaccessible (that is, incomprehensible) text-photos – now simply pleasing calligrammes in white on black grounds are no longer employable as messages, they are poignant echoes of the act of cognition. What saves them from being more than noble nonsense is their positioning within the museum? Here, they are orphans of context, like so much writing, écriture, in the museum-of-the-book.

The extraordinary Sententia I-LXII consists of a tall, beautifully crafted cherry-wood cabinet within which is a hanging rack system for storing and displaying photographs – Grauerholz’s own, in this case. The racks, which pull out one at a time, are made so that they hold photographs on both sides (thirty-two racks, sixty-four images). The images available on one side of the racks are, as Grauerholz pointed out in her talk at the gallery, “thresholds windows, doors, and so on,” while those available from the other side provide “what you might see looking through those former threshold views” (other windows, an interior of another room, a railway yard, a carnival at dusk, and so on). The act of pursuing, sequentially, first subject (on one side) and then context (on the other) in these large, impressionistic black-and-white photographs (typically Grauerholzian in their soft, cinematic muzziness), necessitates a certain amount of prolonged trafficking with the cabinet now a switchboard or transformative centre for, as the artist put it, “lengthening the description of a moment.” The cabinet is now an incarnation of pivotal experiences. The word sententia apparently means both an aphorism and a feeling or opinion; Grauerholz’s mystic cabinet, as reminiscent of the magician’s cupboard as of the arcade or museum vitrine, is thus a sort of palpable swinging door hinged between suggestion and conviction, a bounded, detachable museum of the memory, a small, perfect shard of the architecture of doubt.