[Summer 2000]

by Robert Graham

In June of 1998, fifty-year-old Quebec photographer Alain Chagnon undertook a journey. As a man and as a photographer, he was propelled in flight from the “here” of home in search of what must be found away and somewhere else.

From this particular corner of the continent, he set out west and south to roam and photograph in Kansas and eight other of the much-travelled and -photographed southwestern United States, including Colorado, Arizona, Utah, and California.

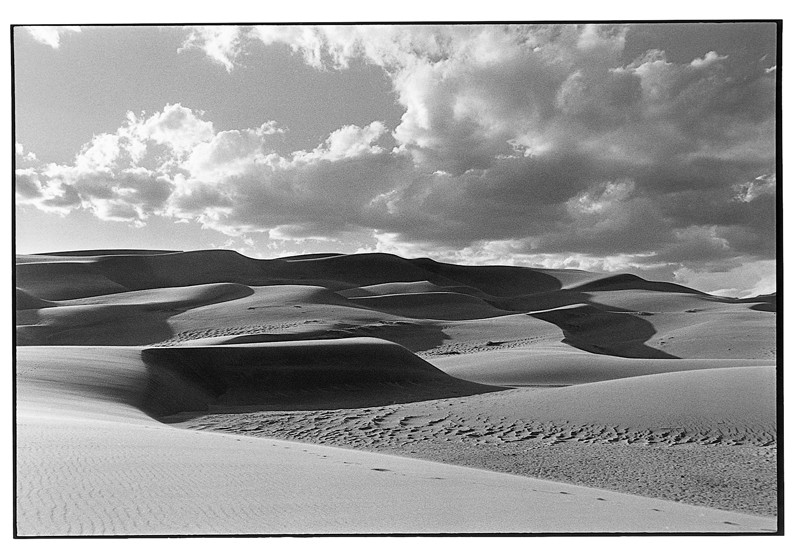

From his travel work, Chagnon assembled a continuous ribbon of sixty-two black-and-white images for an exhibition at Galerie Mistral, in Montreal; presented here, in a slightly revised version, are more than 40 images in long strips. Of uniform height but varying width, the band of photos directs viewers in a left-to-right sequential reading. Not the usual exhibition matrix of discrete images, this arrangement presents a narrative chronicle, an itinerary, of Chagnon’s trip. Within the overarching schema of the work, there are also sub-groups of images that are bound together and display short narrative chains. For instance, in a sequence of four photos from Great Sand Dunes National Mountains in Colorado, we are first shown a pair of shoes in the sand, then a line of footsteps in the sand, then a mid-distance sand dune, and finally a distant peak surrounded by the famous sky of the American West. This sequence, in moving from close to far, displays a cinematic sideways and upward panning motion as well as the trajectory of a human identity being swept up from the grounded footpath to that big oceanic sky. The progress of the sequence is in the path that the string of images describes. And while that path is physical, it is more crucially metaphoric, for Chagnon’s journal is as much personal and spiritual as it is worldly travelogue.

While the street photographer, the photographer of the urban landscape, is a pedestrian, the road photographer is a driver. Chagnon begins with a shot of a Kansas water tower taken from his car. The second image is a self-portrait taken in the car on Route 80 in Wyoming (Chagnon does not title his works, but he locates them, identifying each shot by place, month, and year, and sometimes subject matter). This early inclusion of himself in the project marks the personal turn that he is making here. Besides the usual display of his social sensibility and concern for human particulars, he also wants to show us his own pathmaking.

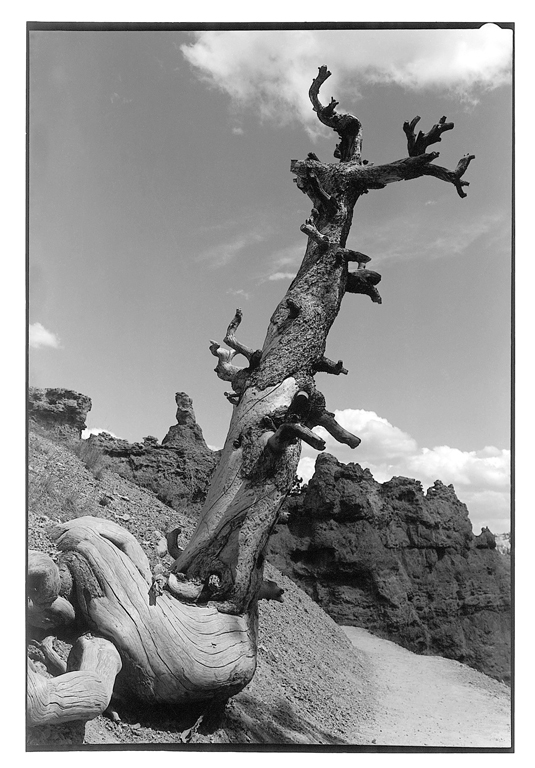

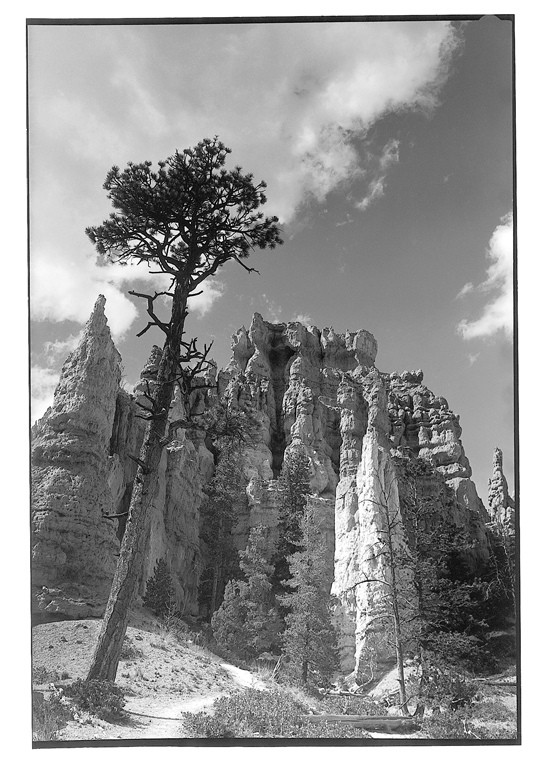

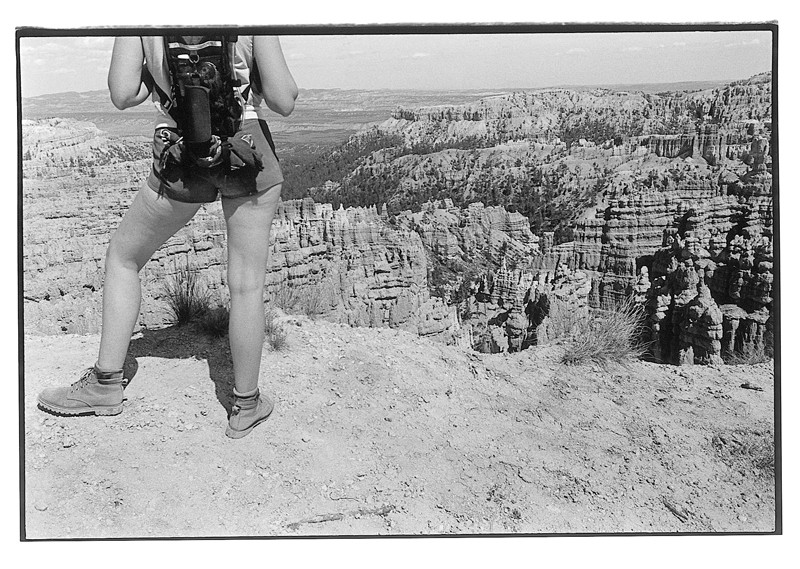

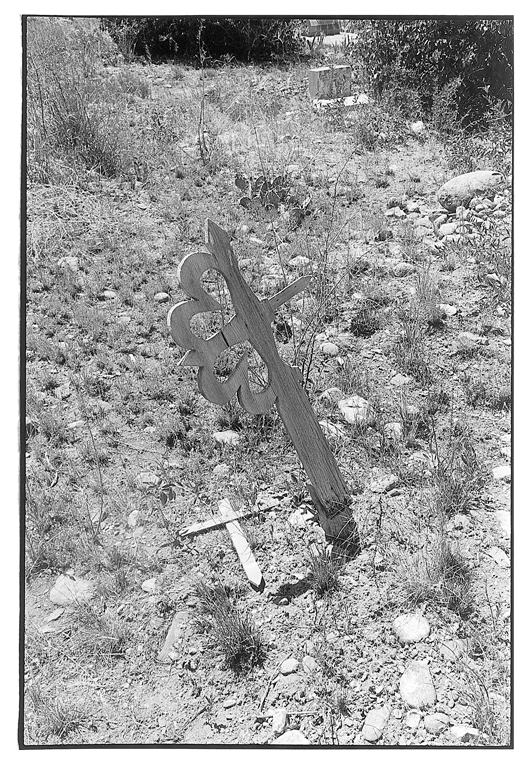

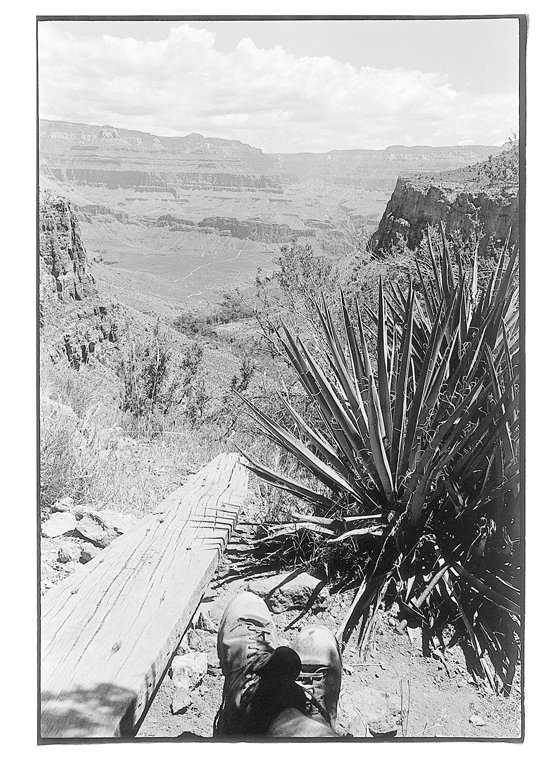

While the tradition of the street photographer is to be curious and outward looking, the road photographer presents a model, or example, of self-seeking. Road work is quest work. Confronting issues of identity and mortality, even for a socially sensitive photographer, the temptation is to turn away from the city and toward the desert: empty, stark, compelling, beautiful, and transcendent.

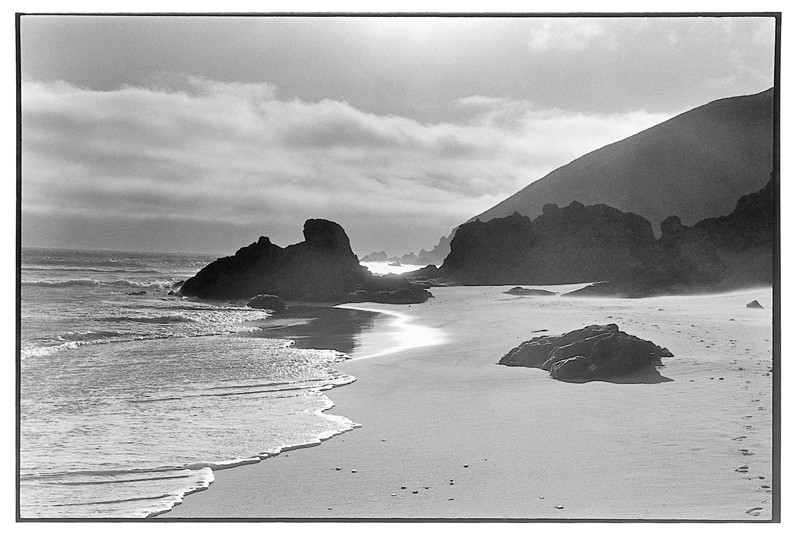

The desert provides the archetypal setting for such life-inquiry. In its emptiness, it is where the self is challenged. It is given the task of being a tonic antidote to civilization. Dry and hard, it is an essentialist, foundational place in which nature is pure, authentic, minimalist, and open. It is also a visually large space that makes us feel our human inconsequentiality, whereas the vast wet ocean makes us feel alone.

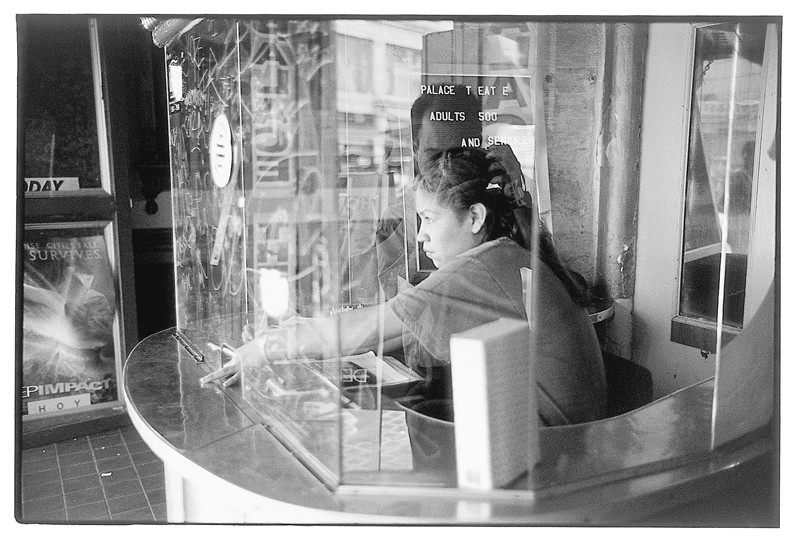

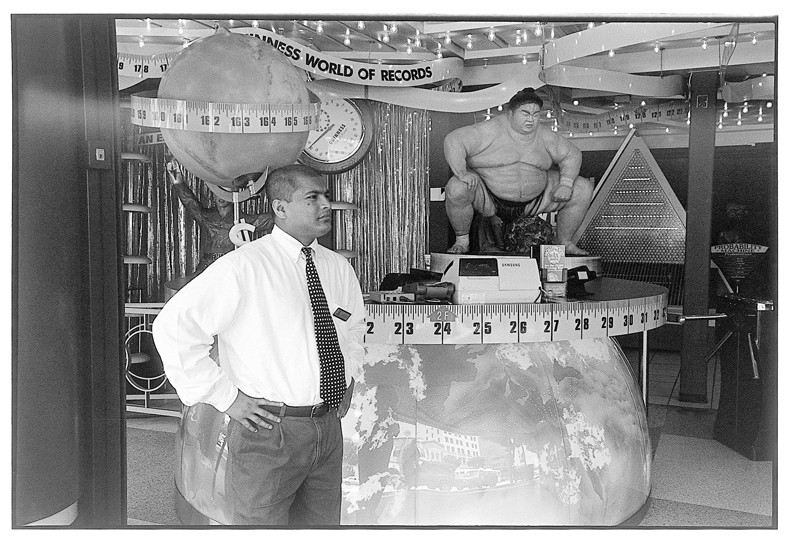

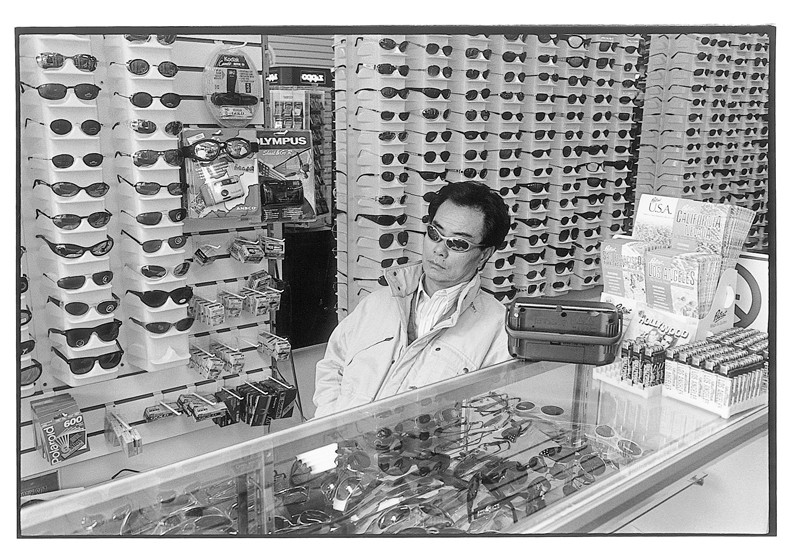

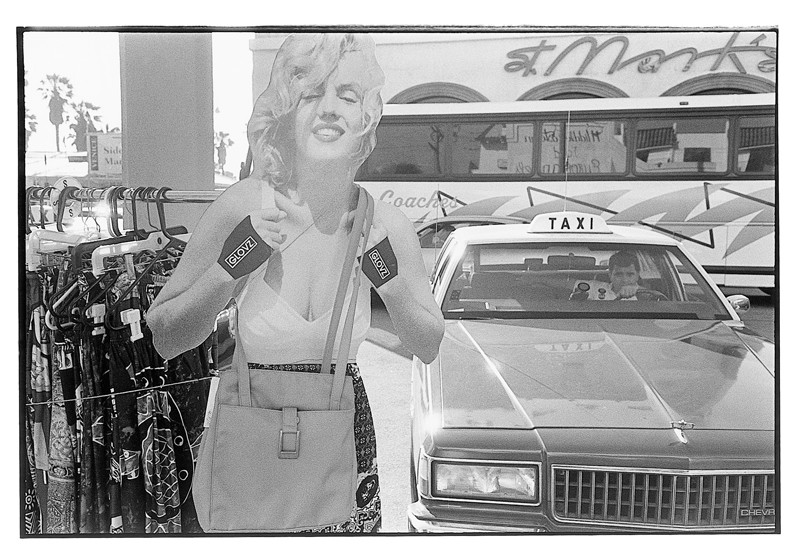

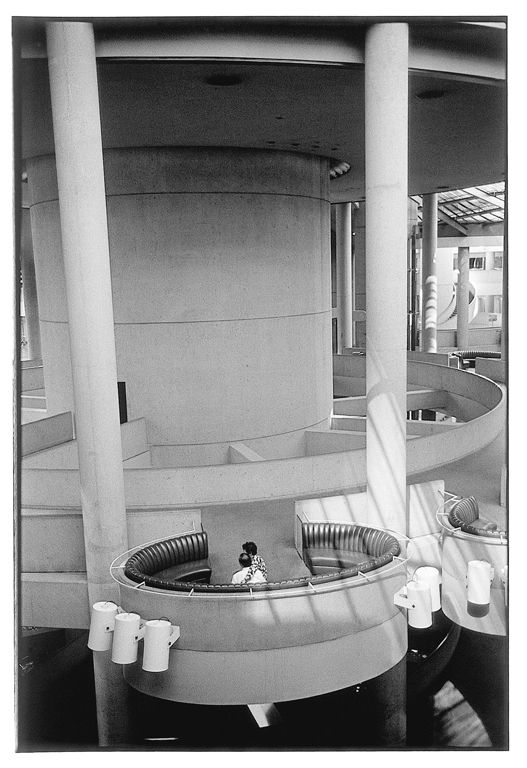

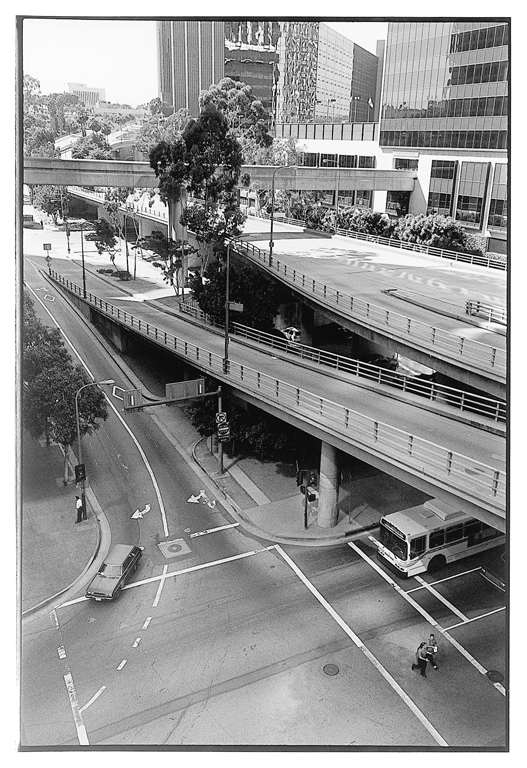

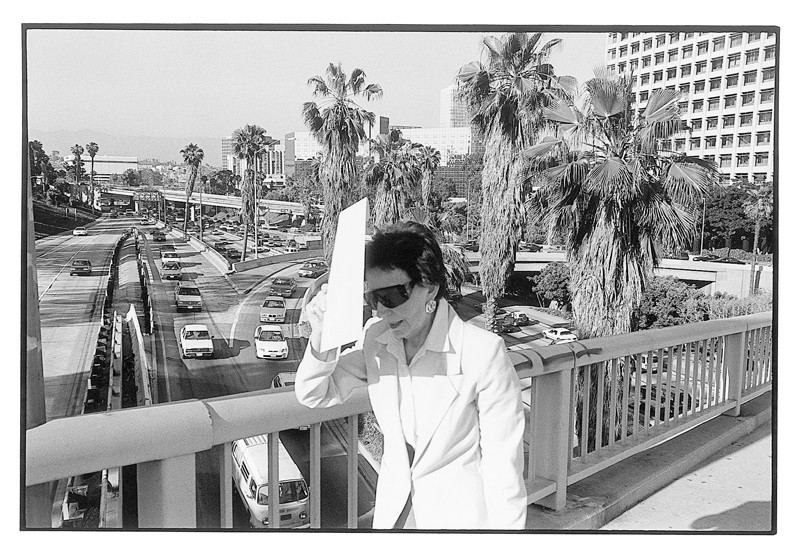

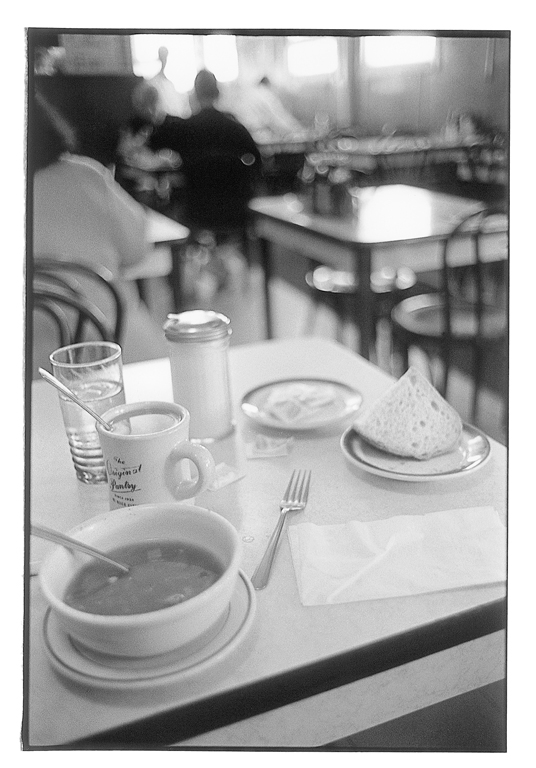

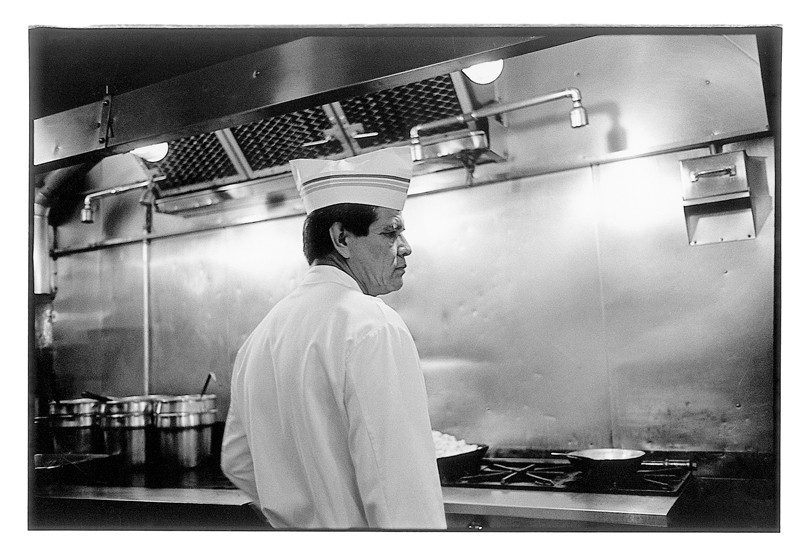

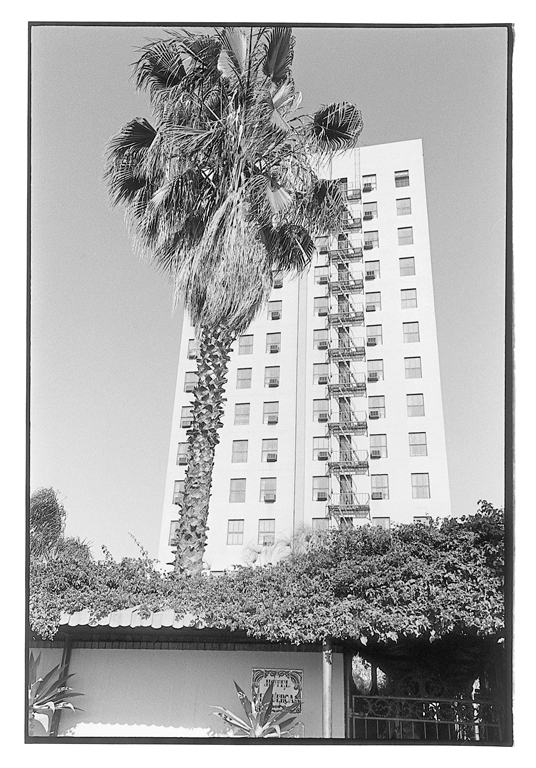

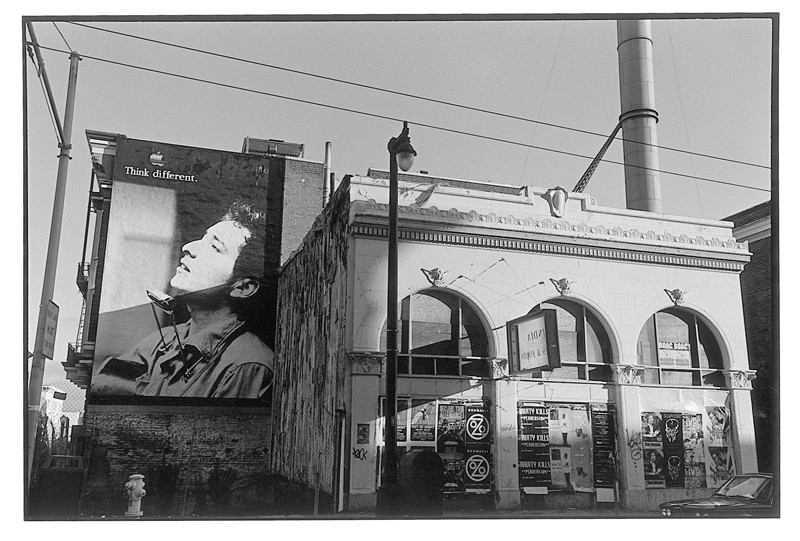

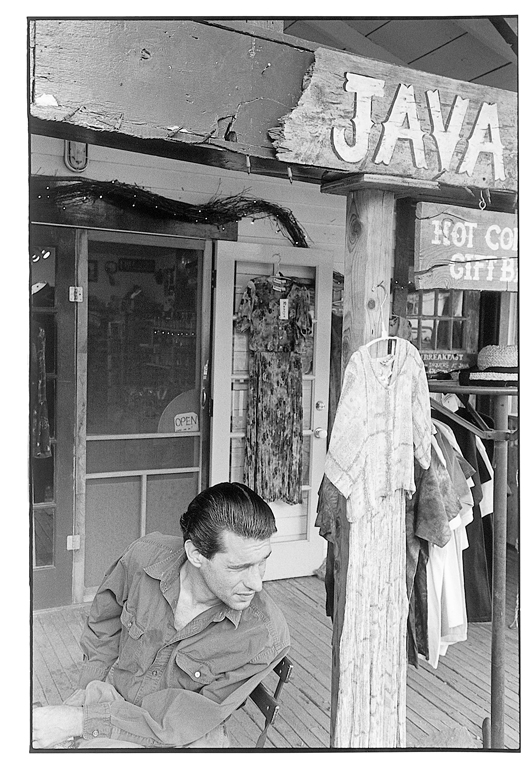

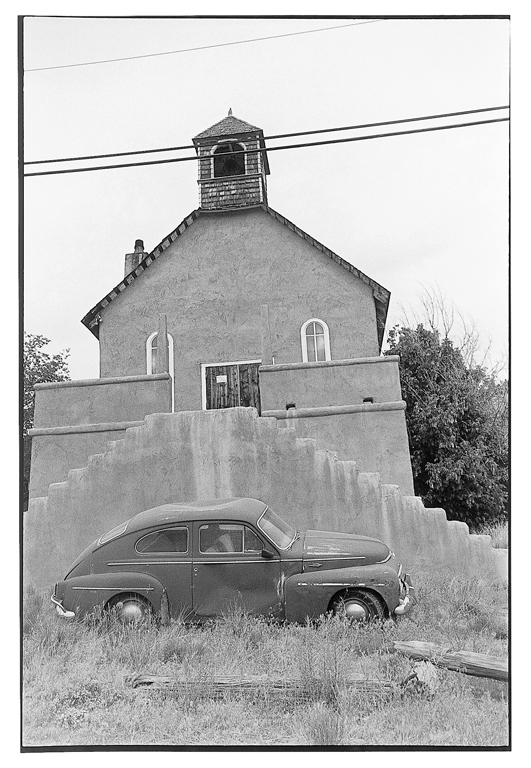

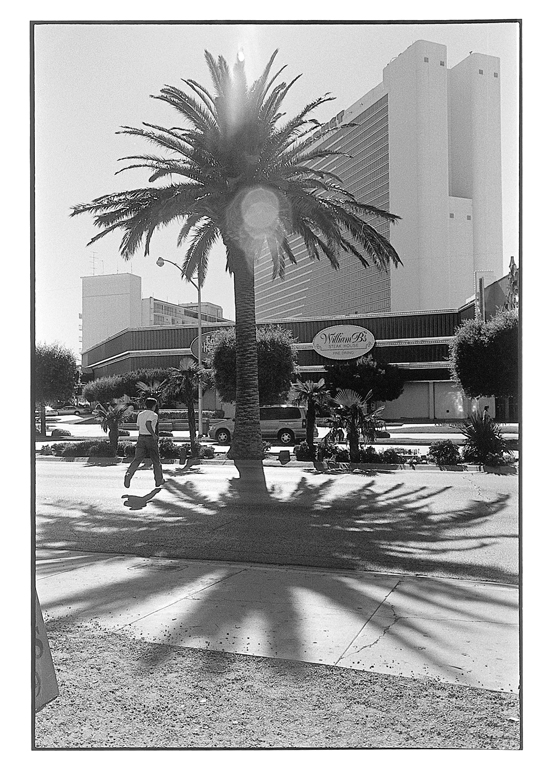

Contrary to the desert itself, the cities of the desert, like Las Vegas and Los Angeles, are highly encultured and aggressively unnatural. Here, Chagnon displays the human encounters a traveler would have while involved in the everyday mundane activities of eating, shopping, driving, sightseeing, going to the movies, and so on.

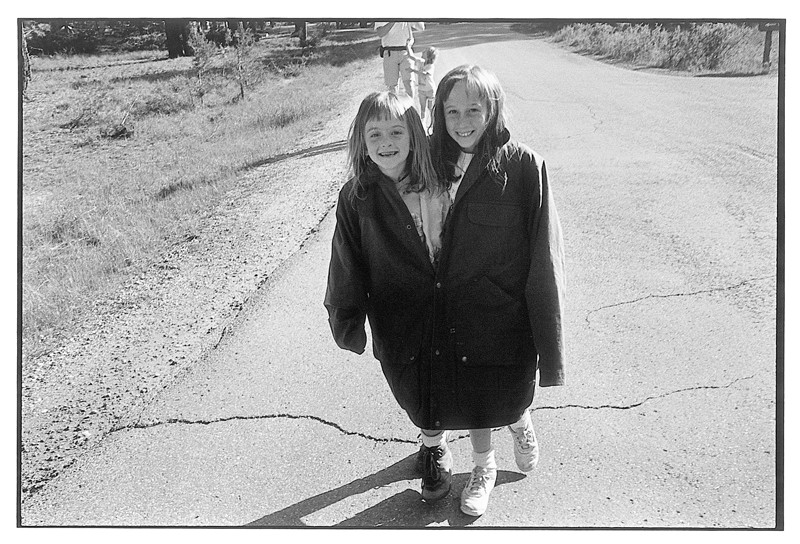

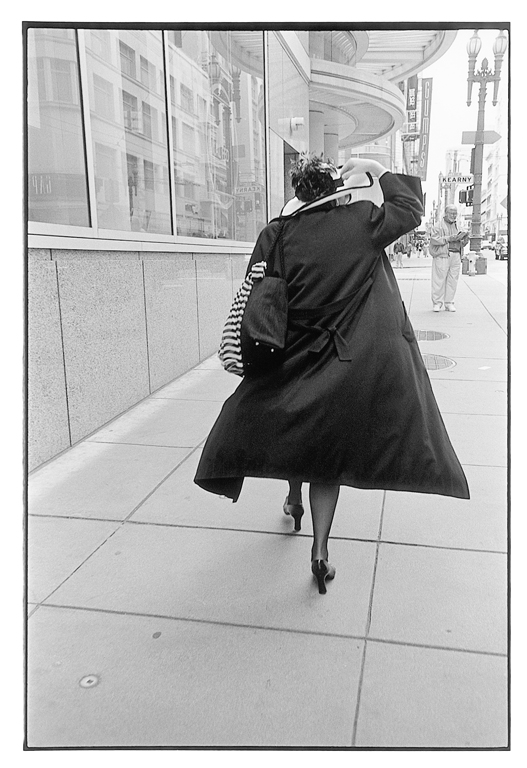

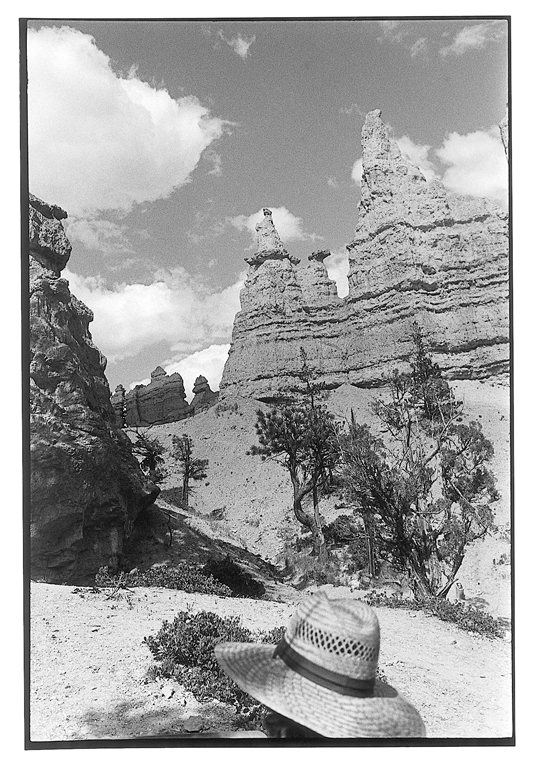

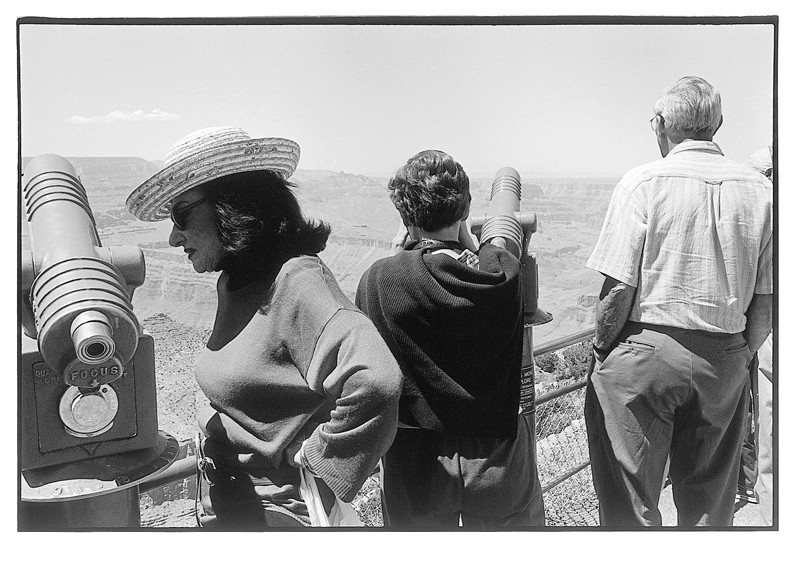

Chagnon favours the metonymies of body parts: truncated figures show just their cut-off feet, legs, their turned backs, or their straw-hatted heads (he has a particular fondness for women in straw hats). He even has a photo of just his own feet setting out on a mountain trail. Yet his human figuration remains sympathetic and democratic. His interest is sincere and open and not patronizing.

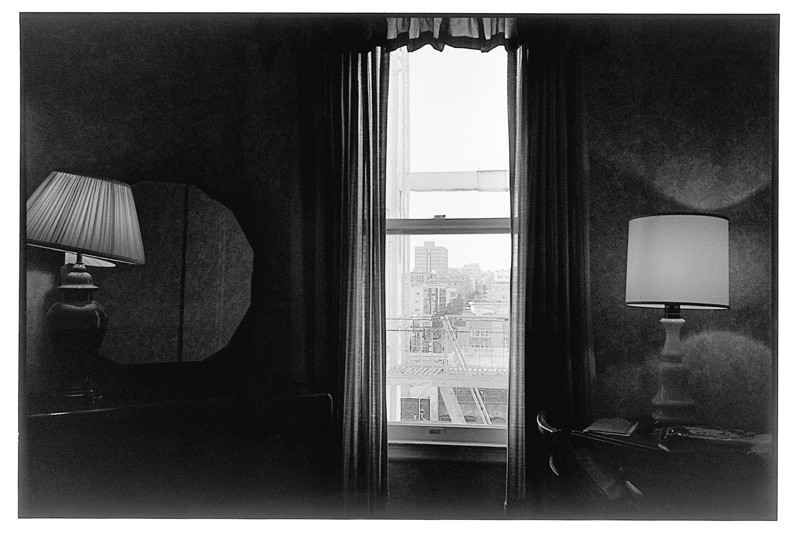

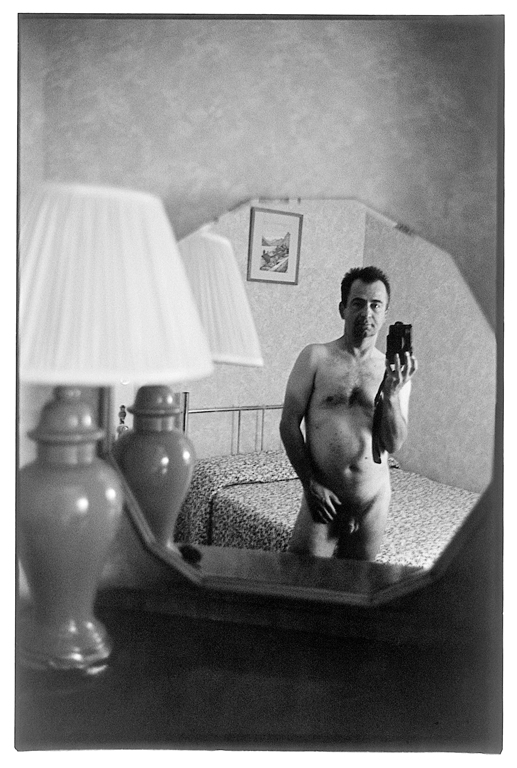

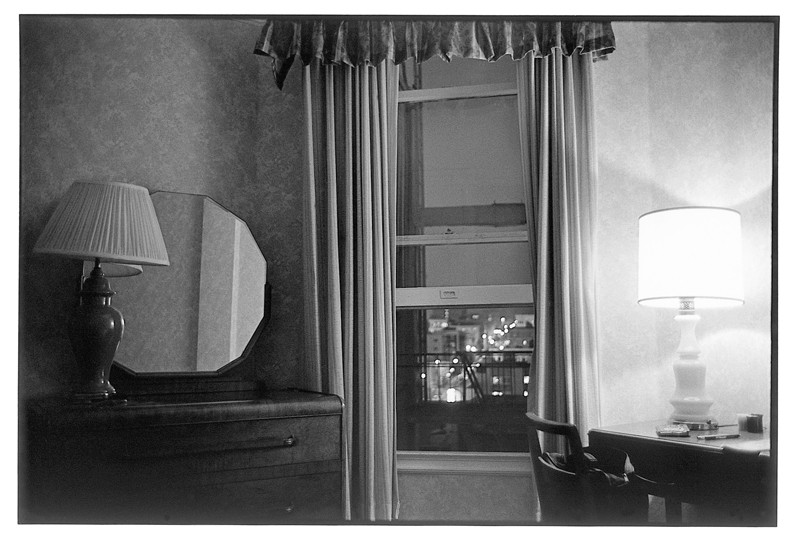

Near the end of the work, Chagnon presents a nude self-portrait taken in the mirror of a slightly shabby-looking San Francisco hotel. While presenting a bold picture, by itself, his nakedness only tells us that Chagnon is a man of a certain age. Yet the trope does suggest the kind of self-discovery that comes after stripping away the arbitrary and external covers we use to clothe ourselves. Nudity as honesty and revelation. This picture maintains and concludes that personal, solitary search aspect of the journey. What gives the image a nice twist and enrichment is that as a link in one of those narrative chains it has on each side of it a windowscape from that same hotel room showing the city outside, by day and by night. Chagnon continues to demonstrate the tension between the mandates of his self-inquiry and his exploration of the external world, between mirrors and windows.

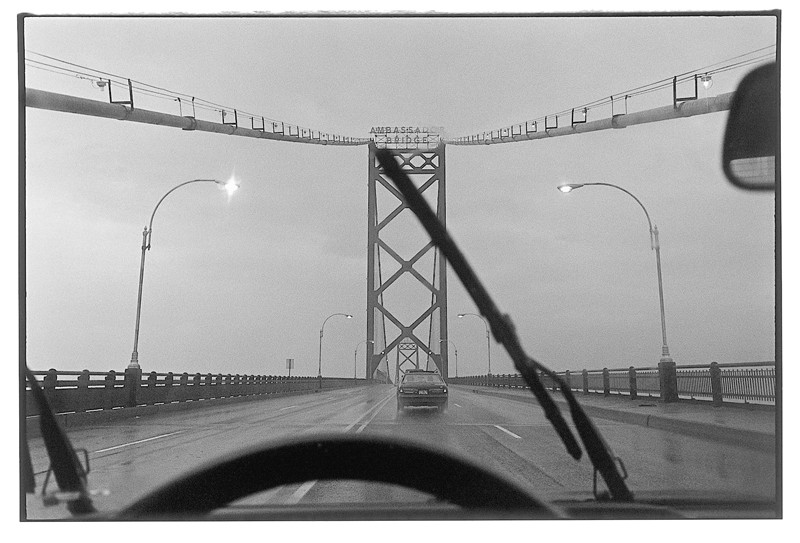

In the final image, Chagnon leaps across the continent from California to Detroit, Michigan. Like a poem’s envoy, it marks the end. Occitan troubadours called their envoys tornadas, or returns, and that is what we have here: the road photographer driving in the rain across Ambassador Bridge in his return home. Returning is part of the journey we bring back what we’ve gained from our going to illumine our home condition. Photographer voyagers bring back disclosures from which we can all benefit.

Robert Graham was born in 1950 and lives in Montreal. Since 1980 he has been writing on art, architecture, and photography for various art journals (including Parachute and C), and for publications of museums such as the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography in Ottawa and the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal.