[Summer 2000]

Meeka Walsh, editor, with contributions by Mary Ann Caws, Robert Enright, and Vicki Goldberg

Winnipeg: Bain & Cox

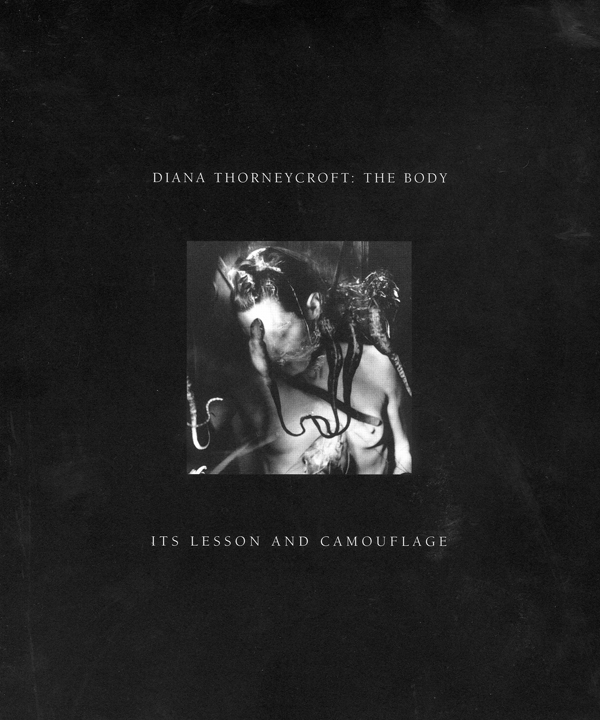

Diana Thorneycroft: The Body, Its Lesson and Camouflage is the first major book by the Winnipeg artist whose psychic explorations have been seen and much discussed in Canada for over a decade.

All of Thorneycroft’s photographic series, beginning with the so-called family pictures, Touching: The Self, are presented in the book, which has been beautifully designed by Susan Chafe and produced to a very high standard by editor Meeka Walsh. Four texts – three essays and a two-part interview – capture the critical and public discussion that has surrounded and, to some degree, shaped Thorneycroft’s production. Walsh deals very systematically with the work, situating it within the discourse of the gendered gaze and picking out key works that can be linked with nineteenth- and twentieth-century female stereotypes. She argues, of course, that Thorneycroft both uses and disrupts them. Robert Enright’s interviews (1996/1999) delve into Thorneycroft’s motivations and her ideas about the reaction to her work. A key question arises from the concept of transgression: is the work/artist transgressive? Thorneycroft wavers in her opinion. The American photographic historian Vicki Goldberg does not. Her review of community standards is detailed and informative, though oddly disapproving of Thorneycroft (odd in a book of this kind). Literary specialist Mary Ann Caws offers a solid counterpoint to Goldberg. Caws is informed by surrealism; she responds eloquently and viscerally to the work.

The look of Thorneycroft’s works is very distinctive. They are all tableaux, created in a shallow theatrical box in her studio or on a borrowed set. Most of the images are self-portraits, though this is not always clear from the title. The compositions are very full, pulling from a repertoire of symbolic objects that she collects or assembles – dolls, stuffed and dead animals, tree parts, and medical and military paraphernalia are her usual props. Her slim body and the use of prostheses blur her sex; in addition, she is frequently masked. In the early works, these were photographic masks, the faces of her family. They were then for a while much more complex, often featuring tubes (or snouts) that covered her mouth. Lately, she has been blindfolded. These elaborate constructions are unified by her lighting technique, which is to paint herself and her surroundings with a flashlight. She thus works mainly in the dark, leaving something of the results up to chance.

Thorneycroft has been actively exhibiting her work in a series of installations that have gained her some notoriety in Canada. This book addresses the controversy without dwelling on it. It offers a welcome opportunity to see, really for the first time, and assess the results of what Caws calls Thorneycroft’s “quest.” Progressing through the series – pictured memories, fantasies, and dream states – we come finally to a relatively simple image of Thorneycroft holding a dead rabbit to her chest. She is cradling it, as Joseph Beuys once cradled and stroked the dead hare; her eyes and mouth are revealed. There are no doubt hidden elements in this picture – Thorneycroft enjoys the secrecy of the hidden decoy – but the face of the subject is naked. She can see now, and she can speak.