[Winter 2000-2001]

This project marks the first time that Faigenbaum photographed subjects with which he felt no special personal identification or emotional connection. The nature of the assignment and his lack of familiarity with the place prompted him to adopt a novel way of working that was more informal and impromptu than in previous works.

During several visits to Bremen, he explored the city, photographing things and people he encountered.

by Gregory Salzman

Patrick Faigenbaum’s Bremen pictures (1996–97) are the result of a commission by the Neues Museum Weserburg Bremen. This project marks the first time that Faigenbaum has photographed subjects with which he felt no special personal identification or emotional connection.

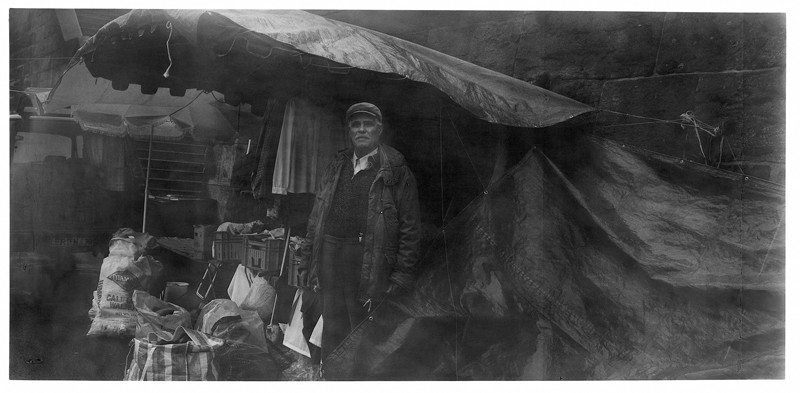

The nature of the assignment and of his unfamiliarity with the place prompted him to adopt a new, more informal and impromptu way of working. In the course of several visits to Bremen, he explored the city, photographing things and people he encountered. Overall, the resulting pictures present a broad sampling of life in Bremen without any sense of an overarching agenda or a priori determination of subject matter. The more open and extroverted character and wide-ranging subject matter of the Bremen pictures in relation to the preceding Prague pictures, is, one suspects, indicative of the vibrant tempo, cultural heterogeneity, and geophysical extroversion of Bremen, given its location and identity as a seaport.

In a Cafe in the Neuen Vahr (1996) is a transitional work that recalls the earlier Prague pictures (1995) and the portraits of the Italian aristocratic families (1985–87), and also reveals a new informality and cinematic character. The composition verges on monumentality yet maintains a personal scale and sense of contact. The tonalities are dense. Detail is almost entirely absent in the coat and woman’s face. The volumetricity of the figures is more fully apparent to the viewer from a certain distance. As one approaches the picture, its plasticity and dual sense of spatial depth and compression are lost. The privacy of the scene is mitigated by the picture’s public character, partly affirmed by the picture’s command of a certain viewing distance. Accents of white in the man’s collar and the woman’s earring endow the picture with impressionistic immediacy and offset its predominant gravity. The picture has additional features reminiscent both of Degas’s and Vermeer’s painting. Compositional stasis and inertial massiveness are offset by the slow passage of light through the picture and by the subtle deviation of the postures of the two figures from an emphatic planarity underscored by the horizontal division of the wall. The woman’s head turns slightly outwards while the man’s torso and head leans and turns inwards, away from strict orthogonality. The man’s shoulder seems to project out from pictorial into actual space, whereas the woman appears to be farther back and firmly planted in pictorial space. The size of the figures, which approximates our own, contributes to the physical connection we experience with them. We interpret the picture phenomenally through a sense of shared embodiment.

In Bremen, for the first time, Faigenbaum began taking colour photographs, and this novel impulse has likely to do with the superior capacity of colour to represent the contingencies and vibrancy of urban life. Also, in Bremen, he began varying his heretofore preferred square format. Some of the Bremen pictures, such as the one just discussed, have a horizontally elongated, although not fully panoramic, format. What further differentiates these from panoramas is that in them there is no panoramic conveyance of the gaze from one point to another. True to Faigenbaum’s aesthetic in general, the horizontally elongated pictures are structured compositionally around the maintenance of a central focus and a lateral balancing of the pictorial elements.

Liebfrauenkirchhof (1997), another elongated picture, contains both a central stabilizing focus and also something of the haphazard fluidity and (dis)organization of urban life. Like the majority of Faigenbaum’s black-and-white pictures, the tones in Liebfrauenkirchhof are very dark; yet, the picture is luminous. One peers into its darkness and, slowly, it divulges its physical contents. Gradually, as one continues to survey it, the picture appears to brighten.

Among the random groupings and milling of people in the town square, one spots a couple who are set off from the rest of the crowd and are facing each other, stomach to stomach. This odd duo anchors the composition in a firm but subtle way. They are located just off-centre enough to blend readily back into the crowd without fully fixing or claiming our attention. After spotting this curious detail (which is too crucial to the picture to be purely inadvertent but whose understated presence supports the contingency of its composition and attests to the unpredictability of urban experience) one’s eye returns again and again to it in the course of one’s divagations through the picture. The central shaft of light on the building in the background also anchors the composition and, through its irregularity and suggestion of movement, animates it. At the base of this shaft of sunlight one glimpses a statue of Grimm’s Bremen town musicians. Its shape rhymes with those of the two small spires silhouetted against the blank sky in the top right corner of the picture, and this “rhyming” helps to distribute the focus of attention throughout the picture. The top right section of the picture, via its opening and deepening of the pictorial space and peripheral pull of attention, contributes to compositional flow and eccentricity. The arresting shaft of sunlight on the building also marks time and invokes a creeping movement that matches the tempo of our apprehension of the picture. Fortuitously or otherwise, the generally crepuscular tonality of the picture merges with the time at which the picture was actually taken, dusk.

The luminous gravity of Faigenbaum’s black-and-white pictures, together with their ambiguous compositional stability and contingency, entails a slowing down of the mind and conversance between inwardness and alertness of mind. The enveloping semi-darkness of these pictures has a similar effect upon us as dusk itself, which stills, gathers and focuses the mind and intensifies perception, especially of colour and atmosphere.

Typically, Faigenbaum’s palette in his colour pictures includes black as one of its elements. Thus, the black-and-white and colour pictures, despite their unequal vibrancy, both possess a certain gravity and interiority. Faigenbaum’s colour schemes tend not to be vibrant, but to depend on a subtlety of contrast and closeness of value that corresponds to the tonal gradation and fullness of the black-and-white pictures.

The unobtrusive, natural mise-en-scène of Faigenbaum’s pictures supports their dual, ambiguous character of separateness (compositional self-containment) and closeness (contiguity of and continuity between pictorial and actual space). Their statuesque immobility and solidity is accompanied by their confirmation of flatness. Immobility and physical tangibility are undermined by the passage of light through them and by their dimensional spatial inflection away from and toward flatness. The exceptional gravity of Faigenbaum’s art is accompanied by its luminous fullness and exhalation.

The juxtaposition of colour and black-and-white works in Faigenbaum’s exhibitions and books, beginning with the Bremen project, underscores a novel cinematic character that unfolds in Faigenbaum’s art at this juncture. Juxtaposition of the black-and-white and colour pictures encompasses the sudden and manifold transitions between inwardness and extroversion that exemplify urban experience. As a consequence of the increasing disparity (of structure) and diversity (of subject matter) evident in the Bremen work, Faigenbaum sensed both an opportunity and a need to articulate relationships on all levels (thematic, formal, emotional) among these heterogenous pictures and across their differences. This new interest and scope is especially evident in his careful juxtaposition of the pictures on the gallery walls, where the spaces between neigbhbouring pictures constitute breaks or gaps in space/time and the elements within the pictures and of all the pictures in relation to one another are co-ordinated through a principle of cinematic montage. The heightened tension between the interconnectedness and the discreteness of individual pictures and their internal elements evident in the Bremen and more recent work appears to be the topos that will inform and propel his future work.

Gregory Salzmanis an independent curator and art writer living in Toronto. His current exhibitions include a solo show of paintings by Moira Dryer (AGYU/Toronto), a solo show surveying Raoul de Keyser’s painting (Goldie Paley Gallery/Philadelphia & Renaissance Society/Chicago), and a solo show of new wall paintings by Jessica Diamond (AGYU/Toronto).

Patrick Faigenbaum was first known for his series of portraits of large Italian families, produced over a seven-year period. He then began to depict human presence in the context of specific locations (including a village in Sardinia, Prague, Barcelona, Paris, and Bremen). Since 1985, his works have been largely exhibited in France and abroad. In 1997, his work was included in Documenta X. He lives and works in Paris.