[Spring 2003]

Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography

21 September 2002 – 12 January 2003

Ken Lum Works With Photography. The title of a retrospective exhibition of Lum’s photographic works at the CMCP in Ottawa this fall mimics the way Lum uses text and aptly describes his practice. Lum works with photography. Rather than exploring the medium as a way to relate and give meaning to the world around him, he consistently appropriates photographic practices of commercial portrait studios and advertising agencies to create an artificial reality closely resembling the world of advertising. The only difference appears to be that nothing is offered for sale.

Lum learned the trade from a commercial portrait photographer, Boon Hui, whom he honours in this exhibition with a large “business card” proclaiming Boon Hui Photography (1987) in red-and-black signage on a yellow board twice as large as the portrait itself.

Lum learned the trade well. The subjects in the early portraits, all gussied up for the occasion, smile at the viewer in overly familiar portrait poses. Rich colours, clear lighting, and fine detail provide a perfect “likeness.” In most photographs, the figures are foregrounded in shallow spaces that do not allow the eye to wander off into the distance. Backgrounds and props – a huge tree in A Woodcutter and His Wife (1990), the backdrop of a city for Nancy Nish Joe Ping Chau Real Estate (1990) – appear to be singularly chosen to add information about the people in the foreground. Texts on boards at least as large as the photographs themselves add to this information. Their content changes with the different series: from names, to a descriptive sentence, to snippets of monologues in the newest works.

Lum distances himself from photography as a tool to make sense of the world and instead treats the medium as the message. Photography and graphic design become a state of being, a one-dimensional world of signs in which private selves become redundant. He made this point early and powerfully in a performance piece titled Entertainment for Surrey (1978), which is shown in a fuzzy video in this exhibition. For four days in a row, during morning rush hour, Lum made an appearance on the side of a ramp feeding into the highway to Vancouver. Drivers quickly began to recognize the still figure and started waving at him. On the fifth day he placed a white cut-out of a figure, representing himself, on the ramp. The real Lum had vanished and was replaced by an empty sign.

He never came back. Rather than reflecting on a postmodern reality of intermingling private and public realms, Lum creates a romantic opposition to an artificial reality that serves as a shield to protect almost invisible private selves. Such a division inevitably creates an adversarial relationship, a struggle between the private life and the public construct, in which the personal is bound to be suppressed. To mingle with Lum’s larger-than-life plexiglass characters is a depressing experience despite the bright colours and the often humorous texts. Signs of real life are minimal.

Graphic design is as close as one comes to personal expression. Barely dressed and blond, the woman in Pamela Gloggins is Candi Sweet (1989) gives the viewer a pouting look from her plush red wing chair. The letters of her name are as curvy as her body, while those that spell “Candi Sweet” have a candy-cane hardness to them. Steve (1986) spells his name in a fan of solid letters crowning his head. Show me your fonts and I’ll tell you who you are! But the vernacular design forms an impoverished personal expression, a sign of fake liberty in a fake world.

In opposition to the artificial, public façade, signs of private lives only sporadically leak through. Melly Shum Hates Her Job (1989) shows a smiling office worker at her desk. It is less choreographed than other portraits, and the text emphasizes that another Melly Shum exists, one not completely reduced to a happy peg in a well-oiled machine. Private lives are also hinted at in the Photo-Mirror Series of 1997, plain mirrors with snapshots from private collections stuck in the frames. They form a relief amidst the glaring, dispirited photographs, but their profound lack of aesthetics also seems to suggest that our private lives belong to a realm of utter banality. Hardly a match for the glossy, colourful lives of the plexiglass people.

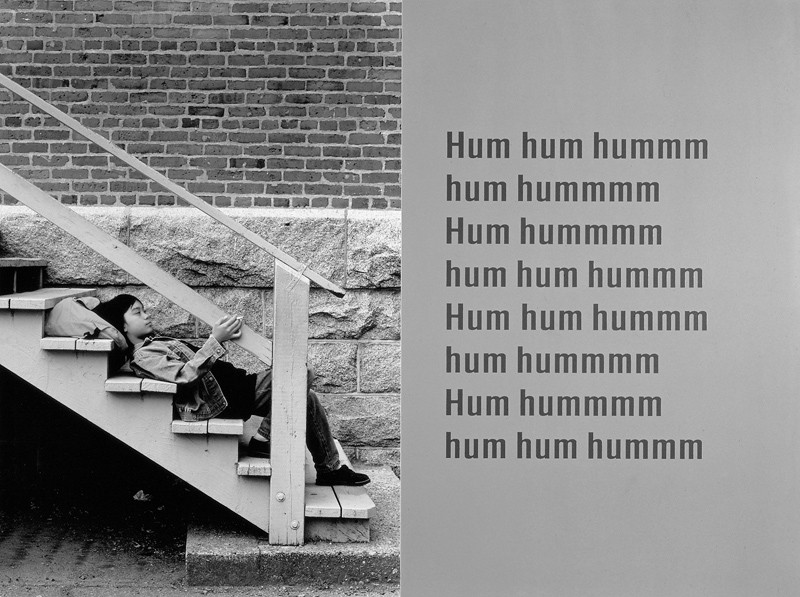

A sense of desperation to break through the artificiality and feel, feel anything at all, pervades the series Portrait Repeated Texts from the nineties. People shown in highly charged slice-of-life situations appear like soap characters mouthing cliché expressions of anger and distress such as Fuck you! you ass-hole! (1993). That’s It, You’re in Pain (1994) shows a drama coach urging a naked man to portray suffering. Conversely, prescribed feelings are shown in Don’t be Silly, You’re Not Ugly (1993), in which a standard pretty blond tries to convince a homely girl of the non-existence of such prescriptions.

Positing the private and public realms as opposing entities leaves little room for political change that depends on infiltration, adaptation, compromise, and transformation. Perhaps this is why Lum’s recent work There Is No Place Like Home (2000), which purports to have real-life political import, falls flat. The work consists of five portraits of ethnically diverse people spouting stereotypical expressions about feeling at home (or not). The most in-your-face is perhaps the redneck shouting, “Go back to where you come from! Why don’t you go home?” How can one expect to create a discussion on the intricate problems of displacement starting from the billboard realities of these actors? Unless Lum is prepared to investigate the complex entanglement of private and public realities, and to leave romantic ideas of opposition and absorption behind, the political relevance and aesthetic interest of his work will remain minimal.