[Spring 2004]

par Dayna McLeod

In “Image #6” of Nikki Lee’s The Punk Project series, two punks are seated on the cement steps of an innocuous building. He has a closely cropped mohawk and wears camouflage pants with a leather jacket thrown across his lap. She wears ripped net stockings over striped tights, and a see-through black blouse with red bra underneath.

She also sports the mandatory studded black leather jacket, spiked chain, and choker, and her washed-out purple-pink hair hangs in her sickly pale face. They are not posing, but caught in casual conversation. The image captures a non-moment – a snapshot that might trigger a time and place in personal memory for the participants or their circle of friends, but for those outside of this circle, the picture is a snapshot of punk itself; an archival image that accounts for thirty years of punk history, from the Sex Pistols’ drug-raging anarchy and middle-class rejection to today’s punk, which seems a sterilized, fashion-plate-industry version of its former self. The image distracts us with these anecdotal, societal, and historical truths, and because it is a snapshot, we do not question the realness or validity of the image – we have seen it or pictures like it so many times before.

The Punk Project is one of over a dozen series of photographs in which Korean-born New York photographer Nikki Lee pushes the boundaries of identity and place, of who we are and how others see us in proximity to the people we choose to surround ourselves with. She places herself within the frame of her images, transforming herself into the documented subject after constructing the context and setting the stage. She performs identity – reinventing herself with the stereotypes, media hype, codes, and clues that look into and out from a given community, infiltrates that community, and presents us with a new version of herself. She is a respectful tourist shopping for who she is within a subculture, stretching the very skin of her own identity to find a fit. Her images dig deep into the construction of community and ego, of social roles and what it means to be self-defined and/or categorized by someone else. She ultimately asks, are personal identity and communal identity fluid?

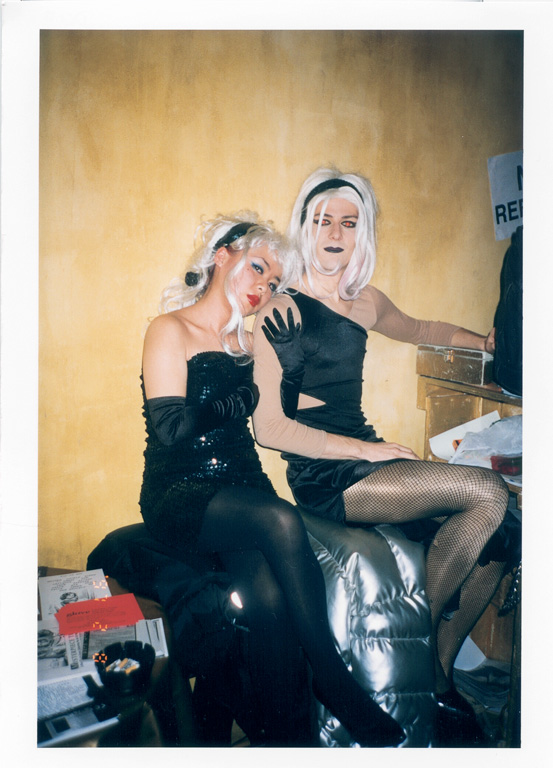

At first glance, there is no question of the authenticity of Lee’s images; we are attuned to this language of image making because we have experienced it. We also know that it is real because it is devoid of the artifice of studio or fashion photography, and the sincerity of the moment captured emphasizes its truth. We are also familiar with artists such as Nan Goldin, who use the snapshot frame with intense, intimate realism. All of these contexts remind us that we are witness to someone else’s memories and are playing voyeur to a stranger’s life. In “Image #5” of The Drag Queen Project, Lee poses in bleached-blonde wig, thick make-up, and tight black vinyl dress with three other drag queens, all dressed to the nines, in front of a bar. In the rest of this series, she struts her stuff to strike a pose with friends – like any self-respecting drag queen, never caught off-guard – always aware of a camera pointed her way. This image and others like it in The Drag Queen Project, in which Lee’s drag queen appears at parties and bars with other drag queens and friends who seem to be on a sliding scale of fun and inebriation, also imply narratives of friendship and community that are universal, and quietly sneak into our subconscious as being unquestionably true. These pictures look like everyday snapshots that may mark an occasion on the personal timeline of the participants, but like an inside joke; those out of the loop miss the punch line. However, our voyeuristic curiosity is tickled and projected narratives fly to figure out the connections between the people in the photographs, to know what fabulous party they were at, to belong to and be included in this narrative, because we all know that these photos and identify with their purpose – to mark a time and place in our own personal histories and to remember the event, friend(s), or experience captured within the frame.

The imagined vision of Lee as artist is egoless outside of her snapshots, as she has built herself many times over from different communities inwards. Lee’s frames are not meticulously constructed: it is the context of her construction that is important. She is not only performing her own subject, she relinquishes control over her frame by handing the camera to a member of her new community, to a friend or passer-by who takes the picture, catching Lee in her new persona complete with context and environment. And Lee does not merely don a costume and play a part like an actress; her practice involves spending time with her new community and experiencing it. Her practice is a performance practice steeped in existential discovery. Like performance artist Tehching Hsieh, “whose medium of expression is not words or sounds or paint, but his own life,”1 Lee’s body of work follows the philosophy of living her content and subject, of respecting and paying homage to it so that she can better understand herself. Hsieh is rigorously committed to his practice, and his most recognized body of work consists of five one-year performances produced between 1978 and 1986. In “Outdoor Piece,” the second piece in this series, Hsieh lived outdoors in Lower Manhattan for one year, where he essentially performed homelessness – becoming invisible and anonymous to those who chose not to see him. Like Lee’s Project series, Hsieh’s “Outdoor Piece” is a performative example of how our environment defines us and how this environment contributes to our personal identity.

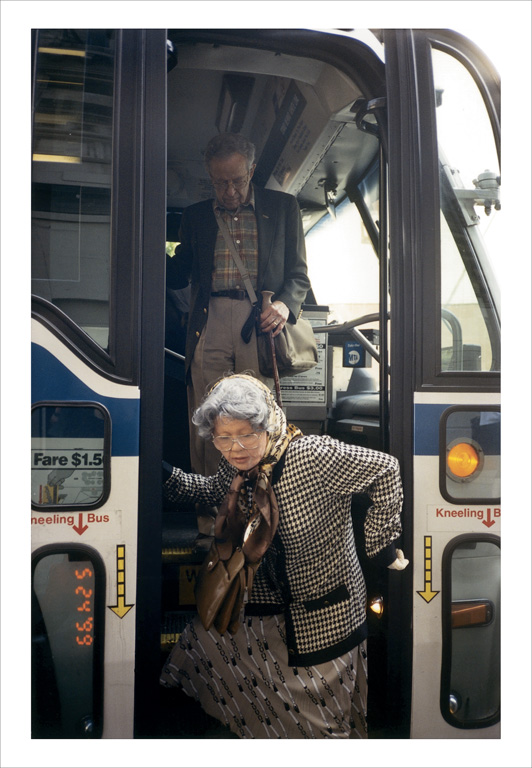

Lee’s Project series are also reminiscent of Cindy Sherman’s meticulously constructed Untitled Film Stills series created between 1977 and 1980. Unlike Sherman, who exploited the visual language of cinema by using single-frame film scenes to re-present and re-contextualize the female subject by fastidiously staging stereotypes of women in film, Lee is not concerned with “woman” or “female” specifically, nor is she particularly focused on deconstructing the place of “other” within her Projects; she is refocusing truth by performing within the truths she creates. When seen together, Lee’s Project series act as parallel universes that expose the complex and constructed nature of identity. Once we look past the frame of one of Lee’s single images, past the images that make up one of her projects, and step back to see groupings of punks, drag queens, senior citizens, yuppies, school girls, skaters, lesbians, young Japanese tourists, or exotic dancers, we start to find Lee within all of these frames. She emerges as a cultural anachronism – a “Where’s Waldo” of identity – simultaneously slipping into and out of culturally identified groups. Seeing a selection of Lee’s selves drives us to pay more attention to the categories and naming of these groups, and to examine our own biases and issues about class, race, culture, and sexual politics. In “Image #2” of The Hispanic Project, Lee performs a Latina who poses with a friend at a parade or some other type of outdoor event. Lee wears lip-liner, sculpted eyebrows, hoop earrings, and flowing locks of hair piled precariously on her head, and poses impatiently with hand on hip and challenging stare. Here, we take Lee as Hispanic, the seams of her transformation showing in our own vision. Do we question that she is in fact Hispanic, or do we accept this labelling and become preoccupied and distracted with the reading of her performance of race? The danger here is that as viewers we bring our own baggage to the photograph and may project meaning onto Lee’s intentions that get tangled up in post-colonialist deconstructions and politically correct analysis. Because Lee readily performs race, class, age, sexual identity, culture, and gender, her work cannot simply be reduced to an ethnographical attempt at depicting “Otherness.”

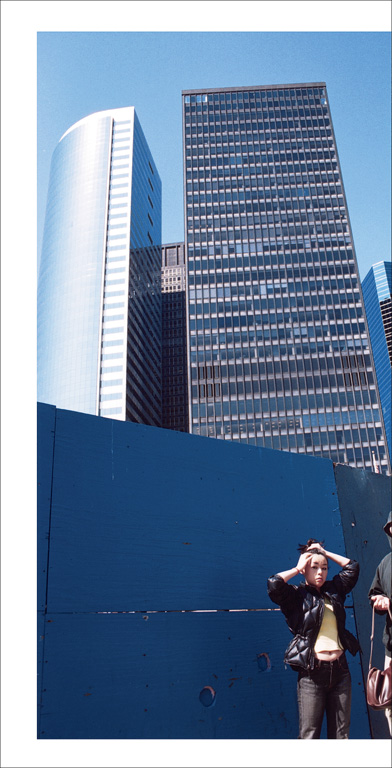

Lee exploits her audiences’ familiarity with snapshot photography at a time when anyone and everyone is increasingly playing the part of photographer – the consumer landscape is flooded with digital cameras, Webcams, and picture-taking cell phones that make models or photographers of us all. Lee is able to sell us multiple lines of truth through the universally understood logics and voice of the snapshot. Her audience can identify with those within the frame and/or the person taking the picture because we have experienced both roles at some time or another. Parts, Lee’s latest series, continues to explore this language of the snapshot and its dependency on narrative. She adds another layer of interpretation and places an importance on the reading of the images by removing sections of them – people, buildings, skylines. Parts are missing from each image, leaving us to wonder about their absence and the significance of that absence. Lee uses the white border typical of snapshot processing to indicate that the image is incomplete. This border allows the images’ content to seep out into a gaping space, where we project and fill in the missing pieces.

In “Part 15,” skyscrapers loom behind a blue construction wall in the background with Lee in the foreground, hands in hair. It is a typical tourist photo that catches its models not at their best – someone with a purse stands beside her – but Lee’s editing line slices through this woman, and half of the picture is removed. What is it that has forced the artist to remove this section? Why hasn’t the whole image been discarded? What is it about the remaining piece that has kept it from being trashed? If we put ourselves in the place of an impartial editor and look at the formal components that make up this image, then perhaps we avoid the temptation of the narrative path and understand the composition objectively. Blue sky frames the two perspectively distorted skyscrapers at the top, and the blue construction wall both contains these buildings and analogously mirrors the sky. The white border mimics the line of the buildings, but the eye leads the mind to the figure at the bottom, and her missing image partner(s). We cannot help but be drawn into imagined narratives, and it is this interactive component that makes Lee’s “Parts” series so successfully intriguing.

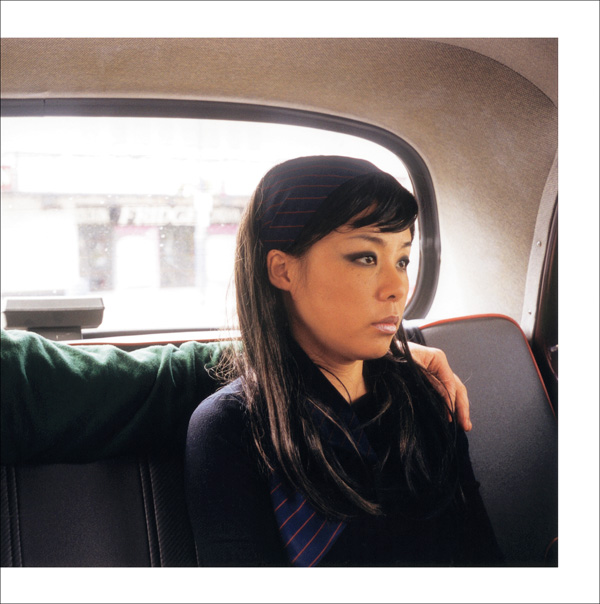

“Parts” plays with missing narratives and actively engages the viewer, exposing a triangle relationship between who is in the frame, who has been removed or excluded from the frame, and the viewer. We become forensic detectives looking for narrative clues to the story that Lee is withholding from us. In “Part 14,” a stoic Lee sits in the back of a car staring ahead. Her hair is styled, her make-up is fresh but not overdone, she wears black and has a patterned scarf thrown stylishly around her neck. An arm extends from outside of the image around her neck; the hand rests on her shoulder. This is all we are allowed to see of this person, the rest having been cut out of the presentation. Lee is controlling what we see but tells us that we are missing something, teasing our voyeuristic curiosity to know the full story. “Part 14” stimulates narrative projection because of the intimacy implied in the mysterious arm around Lee, and her stiff posture and expression. What has happened to this woman? Who does this arm belong to? Is she compromising herself in a relationship with this person (whom we confirm to be a man after accumulating and speculating on the heterosexual clues dropped inside and outside of the frame), and where is she going?

A frame slows a moment to a standstill – capturing the essence of experience – and promotes it as memory. Snapshot photography is all about this essence and the spontaneity of its capture, of transforming the banal and everyday into instant markers of time and experience. Lee manipulates our nostalgia for snapshots, our voyeuristic curiosity, and our desire to fill in the blanks – to know the full story, to see the entire picture. She exploits assumptions implied in the personal leaving us to grapple with what is inside and outside the frame, and how that frame became a reality in the first place. Lee’s images encourage us to question the artifactual integrity of snapshots, culture, and community while allowing us to enjoy the many faces of constructed identity and memory.

1 Steven Shaviro, “Performing Life: The Work Of Tehching Hsieh,” www.one-year-performance.com, February 5, 2004.

Nikki S. Lee is a Korean-born artist living and working in New York. Since 1997, she has been exploring multiple dimensions of social identity in series of “snap-shot” self-portraits based on immersions into disparate communities (lesbians, drag queens, yuppies, Ohio trailer-park dwellers, skateboarders, senior citizens, Hispanic and Japanese street kids). Lee received a master’s degree in photography from N. Y. U., after training and working in commercial fashion photography. Her work is now exhibited and collected widely. She is represented by Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects, in New York.

Dayna McLeod is a freelance writer and video and performance artist working in Montreal. She has written extensively on art and travelled greatly with her performance work, and her videos have played in festivals internationally. McLeod has just received her first grant from the Conseil des arts et des lettres du Québec for a video production that critiques the pornography industry.