[Summer 2004]

His photo and video-based print works cultivate a dual aesthetic of painterly veils and minimalist colour-field grids.

by Elizabeth Menon

Chicago-based contemporary artist Jason Salavon (b. 1970) employs computers and code to transform material appropriated from popular culture and imbues those sources with nostalgia.

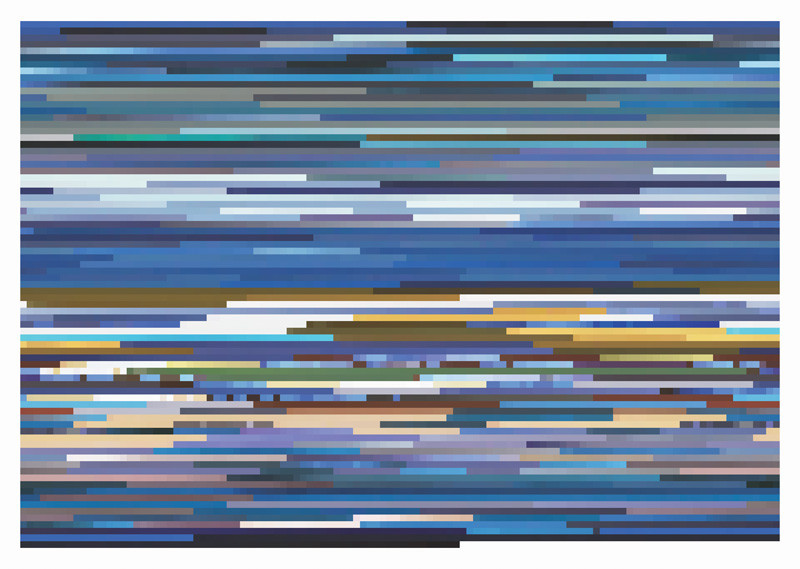

Salavon’s body of work is both distinctive and varied, ranging from digital video installations to Web-based interactive works to collaborations with computers to create paintings that blur the line between manmade and machine aesthetic. In his photo and video-based print work, Salavon similarly cultivates a dual aesthetic, alternately presenting painterly veils and minimalist colour-field grids. In either case, a narrative is simultaneously implied, described, deconstructed, and subverted, as he articulates an aesthetic concept, or a conceptual aesthetic.

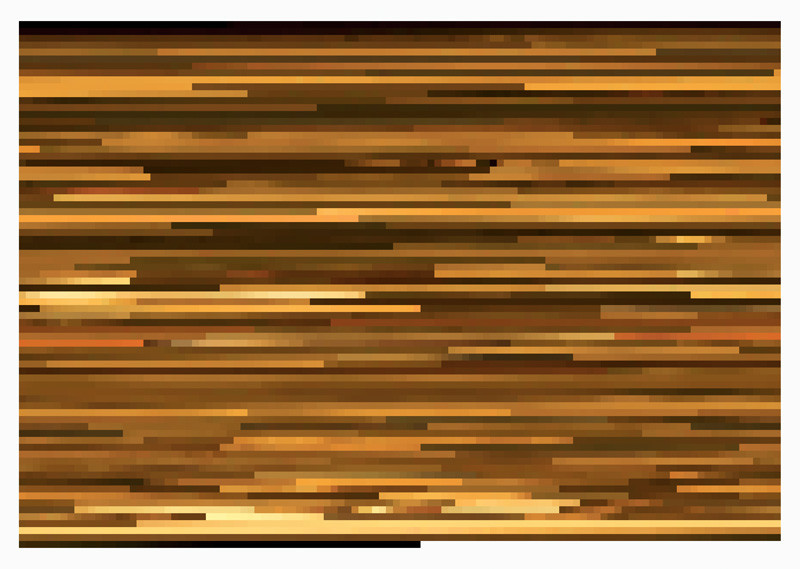

Salavon’s interest in the merging of the concept and the aesthetic has led him to develop processes that allow him to direct computers to create works of art in a collaborative process. The result is database-driven works that reference the apparent reliability of statistical data. The fact is that statistics do not represent absolute truths, and they are consistently subjected to shaping depending on the context in which they are presented. The works in Homes for Sale (1999/2001/2002) are amalgams of realtor photos of single-family homes at the median price range in Chicago, New York City, and Los Angeles. These are sourced directly from the Internet, a vast storehouse of information and images that is easily the most prolific of current popular culture resources today. Inspired in part by the artist’s desire to purchase a home, these works visually reflect the late, form-dissolving style of J. M. W. Turner and the light and weather-effect–driven paintings of the impressionists. This is largely because the same concerns (light at various times of day, weather effects, and seasons, resulting in perceptual colour differences) are manifest in the sourced images, which conform to local particularities (such as lot sizes). Anyone who has searched for a home knows that what is presented in a realtor photograph is unlikely to represent the reality of the property, and that after a while all houses begin to look alike (even more so given the current trend in tract housing). Buying a house, after all, is a romantic dream usually divorced from the realities of home ownership and maintenance. Salavon’s works, produced by mean averaging, layering, and justification (alignment of photographs of an equal size or at equal points), remind us that life is driven largely by averages used statistically to obscure individual results, whether for test scores, gas prices, or waist sizes. Salavon shapes statistical data to yield an aesthetically compelling outcome, simultaneously preventing source material from functioning as originally designed. The information in his statistical works has been reframed as art, much as Warhol and Lichtenstein repurposed prevalent popular culture forms of the 1960s. By inserting a perceptual optical phenomenon in place of traditional presentation of information, Salavon creates a visual experience that preferences the aesthetic over the intellectual. Yet, the work remains reflective of and dependent on the original concept.

In the digital C-prints Every Playboy Centerfold The Decades 1960s and 1990s (1998) Salavon explores and exploits the tropes of centrefold photography, while simultaneously creating an abstraction that denies their original function as objects of arousal. The individual original appropriated photographs are subjected to a mean-averaging process, resulting in an amalgamation that resembles the shroud of Turin and Gerhard Richter’s photography-inspired blurred oil paintings more than the nude women that make up their content. At the same time, Salavon alludes to the historical social situation that glorifies the nude as a time-honoured subject of art history while decrying the same subject as pornographic (and thus not art) in a different, more functional context. The four images in this series present a taxonomy of the centrefold, as changes in preferred poses (frontal versus profile), hair colour, and waist, chest, and hip sizes are tracked through four decades in the shroud-like representations.

Salavon also obscures individual identity while preserving anthropological details in the series 100 Special Moments (2004). Graduations, weddings, and even participation in Little League baseball are all markers of time for specific individuals. Yet the professional portrait photographer imposes a standard composition for these life-altering events. In droves, individuals share these private moments by posting the images in on-line photo albums or blogs. Salavon highlights this dichotomy of the collective personal by removing the functional and documentary evidence of the individual. Through the use of his custom averaging process, a different type of documentation is proposed. As in the Playboy series, these works appear lit from within. Bright voids exist where the detailed facial features of the viewer’s own loved ones are expected and not delivered. Salavon calls the result “generalized contours of structure and rhythm” or “ghosts of repetitious structures.” They could also be called the “deep structures” of contemporary life.

Salavon completes the ultimate disruption and reconstruction of self through digital transformation in Flayed Figure, Male, 3277 1/2 square inches (1998/2001). For Flayed Figure, Salavon had the entire surface area of his body digitally photographed. Hundreds of images of skin were then digitally divided into more than thirteen thousand half-inch squares and arranged vertically by luminosity from dark to light. Reproduced to scale, the resulting work reveals both more than and none of what the viewer expects from a self-portrait. The tradition of this genre includes everything from Michelangelo’s self-representation as St. Bartholomew in the Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel to Marc Quinn’s No Visible Means of Escape (1996) and portrait sculpture Self (1991), made from his own frozen blood. The presentation of the artist’s body as artwork has been variously designed to document individual points of artistic achievement (Picasso) or as a record of ageing (Rembrandt). But Salavon presents another, equally valid truth in asserting that there is precious little separating the artist and the artwork on some level. Salavon represents himself in terms of a particular vital (digital) statistic arranged in such a way as to reflect formal concerns as a further expression of the conceptual aesthetic that bridges modern and postmodern. As R. L. Rutsky states in Hich Techné: Art and Technology from the Machine Aesthetic to the Posthuman, “It is in modernist art that a different conception of technology begins to emerge, a conception in which technology is no longer defined solely in terms of its instrumentality, but also in aesthetic terms.”1

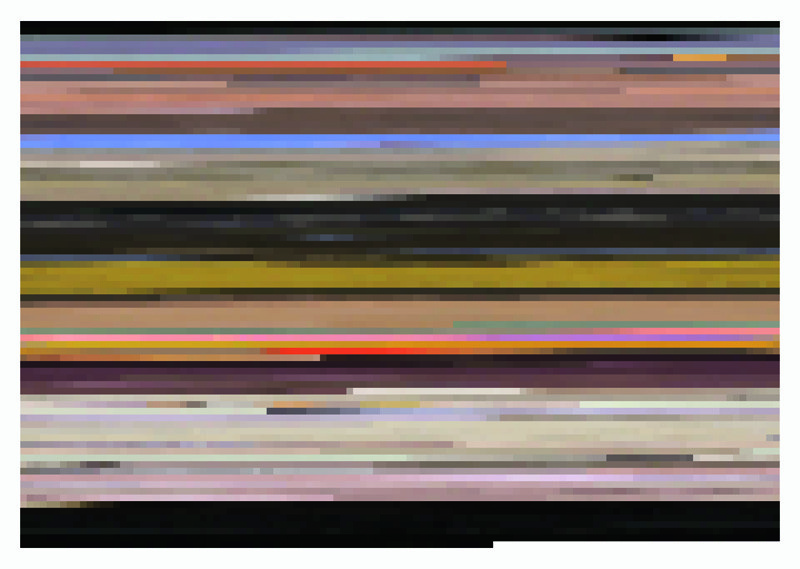

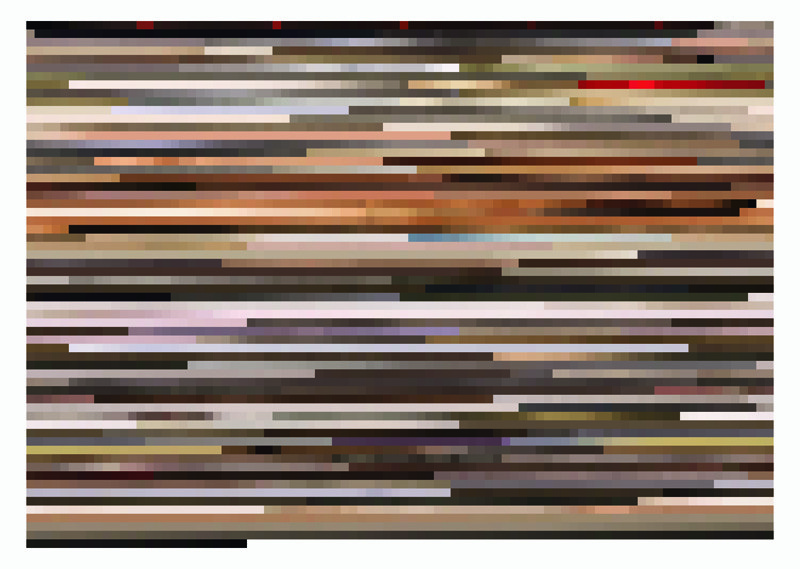

Salavon’s works might also be seen as a type of artistic interference applied to existing imagery. In other works, he manipulates appropriated video, replacing the original narrative content with pure colour arrived at through mathematical averaging. The resulting works “read” as purely visual abstractions, as the soundtrack that not only underscores the narrative progression but enhances it has been removed. In MTV’s 10 Greatest Music Videos of All Time (2001), Salavon has appropriated both the ranking and the music videos from MTV, removed the soundtrack and digitized each video’s visual content, and simplified each individual frame to a mean average colour, which is then presented in its original sequence. The resulting abstractions (which nonetheless carry what could be called a latent narrative content) exist without the two components that make up music videos: pictures and music. The original “function” of the video is removed, leaving pure aesthetics (art) in its place. In a sense, Salavon has appropriated the content of pop art and the form of minimalism. The appropriated material becomes the site of an exercise in perception and focus, demonstrating not only that anything can be art, but that anything can be formalist, modernist art, arrived at through postmodern means of appropriation and manipulation.

Despite the “popular” and frequently non-aesthetic source material that he uses and the ease with which social or political ideas can be extracted from his works, Salavon’s stated approach to his work is aligned closely with parts of Theo van Doesburg’s manifesto Art Concrete: Basis of Concrete Painting (1930) – in particular, that the work of art should be fully conceived and formed in the mind before its execution and that constituent pictorial elements (as well as the final finished work) have no significance outside themselves.2 The mechanical, “anti-Impressionistic” technique advocated by van Doesberg is accomplished by the action of the computer. Unlike concrete art (or, more generally. constructivist principles), Salavon’s work derives its formal qualities from nature and is presented with sensuality and sometimes sentimentality. Using digital technologies, he has transformed and filtered the reality of his appropriated material, creating meta-fictions for viewers to experience in new ways. The clutter of contemporary life is transformed into the rare work of art, a source of abstract beauty and aesthetic contemplation nonetheless reflecting the structures – both deep and shallow – with which society is preoccupied.

2 Theo van Doesburg, “Manifeste de l’art concret,” Concrete (Paris, 1930), reprinted in Joost Balijeu, Theo van Doesburg (New York: Macmillan, 1974), pp. 181–82.

Jason Salavon earned his MFA at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and his BA from the University of Texas at Austin. His work has been shown in museums and galleries throughout North America and Europe and is included in a number of prominent public and private collections. Previously, he was employed as an artist and programmer in the video game industry. His web site is www.salavon.com.Upcoming: Jason Salavon’s work will be featured in upcoming solo exhibitions at f a projects, London (May 13–June 12, 2004), Earl Lu Gallery, Singapore (July 28–August 29, 2004) and The Project, Los Angeles (September 11–October 9, 2004).

Elizabeth K. Menon, assistant professor of contemporary art history at Purdue University, has published in Gazette des Beaux-Arts, Nouvelles de l’estampe, and Art Journal. Her current research addresses new media and technology-driven art. Recent publications include “Ut Pixel Poesis,” in Selected Readings of the International Visual Literacy Association (2003) and “Web Installation Art, Interactivity and User Connectivity‚” in Image and Imagery (2004).