[Spring 2005]

The Truth Will Be Known when the Last Witness Is Dead: Documents from the Fakhouri File at the Atlas Group Archive

AGYU at Prefix ICA, Toronto,

September 16–November 27, 2004

At the heart of history is a critical discourse that is antithetical to spontaneous memory. History is perpetually suspicious of memory, and its true mission is to suppress and destroy it.

⎯ Pierre Nora, Between Memory and History : Les Lieux de Mémoire, 1989

Lebanese-American artist Walid Raad’s relatively recent rise to global prominence in the art world was significantly spurred by the inclusion of his work in Documenta 11, in Kassel, Germany, in 2002. One result of the critical acclaim that he received from that exposure has been a spate of international exhibitions. Consider as evidence of this his blanket coverage of Toronto in the fall of 2004. While this review concentrates on his exhibition at Prefix ICA, titled The Truth Will Be Known when the Last Witness Is Dead: Documents from the Fakhouri File at the Atlas Group Archive, it was not the only opportunity to consider his work, ideas, and influences. The Art Gallery of York University hosted additional, complementary works by Raad, V-Tape presented a video program selected by Raad, and he spoke in November as part of Ryerson University’s Kodak public lecture series.

The Prefix show consisted of four bodies of work utilizing video, text, and photographic images, sometimes in collage form, drawn from a variety of sources. The operating premise of this extremely layered exhibition is that a Lebanese institution called the Atlas Group has been formed with the intention of collecting, documenting, and constructing a history of the chaotic period between 1975 and 1991 known as the Lebanese Civil Wars. What we see on the gallery walls are “files” from the Atlas Group archives. The archives’ constructive goal takes on a special resonance when the exhibition’s title is considered. Implied is that it is only when the immediacy of memory, as sustained by the living, has disappeared that we will “know” what really happened during those bloody years. It is only when history no longer has to contend with the nuisance of first-hand testimony and the vagaries of memory that we will have our definitive account. The question appears to be asked whether history depends as much on its distance from events for its “authority effect” as it does on the expectations of institutionally supported factuality and truthfulness that we bring to it. This idea of distance finds many expressions in Raad’s work – chronological, geographic, psychological, aesthetic, perspectival, and cultural – as is suggested, of course, when one contemplates Raad’s presentations of his work on Lebanon in “Western” contexts.

The question of the effect of distance begins to insinuate itself when one comes to the realization that Raad has fabricated the Atlas Group and its most important contributor, historian Dr. Fadl Fakhouri, whose documentation as organized into discreet files, comprises the work shown at Prefix. However, it also soon becomes clear that knowledge by the viewer of the so-called fictional nature of Raad’s constructions is not, in itself, a key to the work. This knowledge is not revelatory but simply an entry into far more interesting epistemologically driven questions about the very construction of binaries such as those of memory and history and truth and fiction.

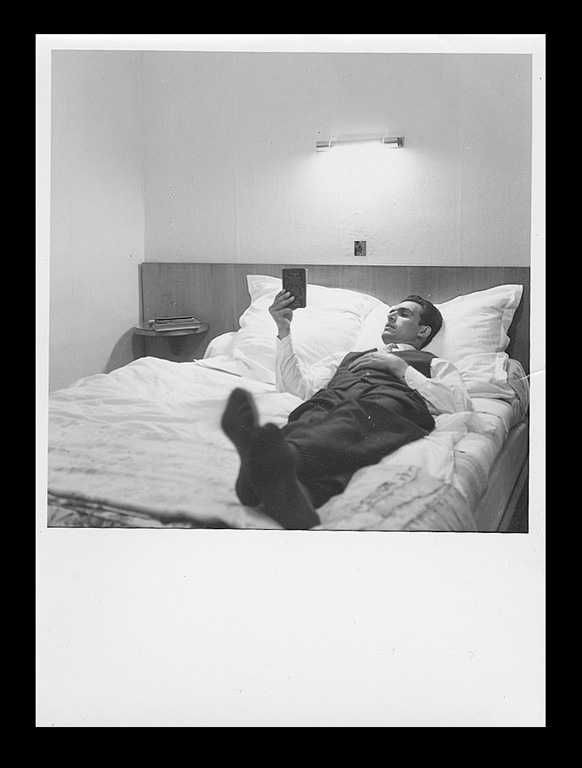

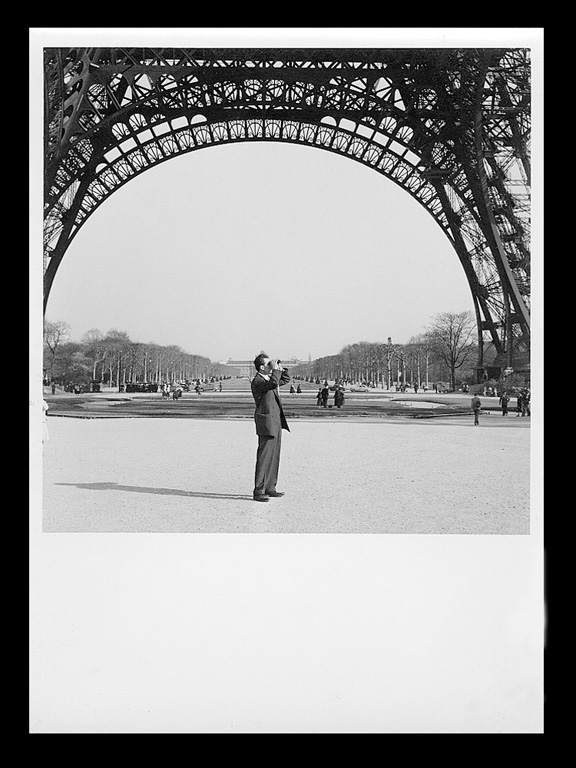

One of the more recent works in the show is identified as follows: Title: Civilizationally, We Do Not Dig Holes To Bury Ourselves; File: AGA_Fakhouri; Date: 1958–59/2003. This work consists of twenty-four snapshot-sized photographs framed to approximately 8″ x 10″ and is presented as a set of self-portraits ostensibly taken by Dr. Fakhouri on his only trip outside of Lebanon, to Paris and Rome, in 1958–59. Again, one is struck by multiple concepts of distance at work – for example, the notion of the physical and psychological distance between home and away and the distance in perspectival space between Dr. Fakhouri and his tripod-mounted camera (he is alone in most of the photographs, usually occupying a relatively small proportion of each frame). The series begins with Dr. Fakhouri in front of recognizable architectural monuments, more or less typical tourist photos. However, as the series progresses, many of the images begin to seem increasingly odd – photographs of Dr. Fakhouri reading a newspaper in his hotel room or anonymous bland outdoors spaces in which we can barely find the man. As we reach these latter images, the question of what they actually signify becomes increasingly pressing. No longer standard tourist fare, they begin to seem more like staged film stills taken by a male Cindy Sherman. Questions of the limitations of photographic documents in explaining their subjects inevitably arise.

Similarly, the piece Title: Missing Wars; File: AGA_Fakhouri; Date: 1975-1991/1999 creates an almost preposterous density of fact. Each of twenty-one framed pages (excluding the two title pages), drawn ostensibly from Dr. Fakhouri’s notebooks, records information about a group of Lebanese historians who go to the racetrack every Sunday. Rather than bet on the horses, they bet, instead, on the ineptness of the racetrack’s photographer, who seems incapable of capturing the actual moment the winning horse crosses the finish line. Small yellowed newspaper photos of galloping racehorses are accompanied by detailed notes on the horses, race distance, average speed, and distance of horse from finish line when photographed. In an additional and particularly absurd touch, Fakhouri’s wife has added handwritten personal assessments of each winning historian’s character (added after Fakhouri’s “death”). Here, Raad’s presentation of the historians’ fixation on instances of evidence that are, once again, incapable of actually proving anything amounts to a satirical reflection on the discipline of history itself and on the contingency of “facts.” In interviews, Raad has spoken of the need to create stories to explain these curious horse-racing photographs he found in Lebanese newspapers. In creating these stories, summoned up are not only the profound contradictions of rationality itself but also the spectre of a day-to-day life that sets itself against Western media representations of the civil wars. These usually comprise images that isolate moments of pain, suffering, or violence, not at all unlike the daily visual fare we are currently being offered regarding life in Iraq.

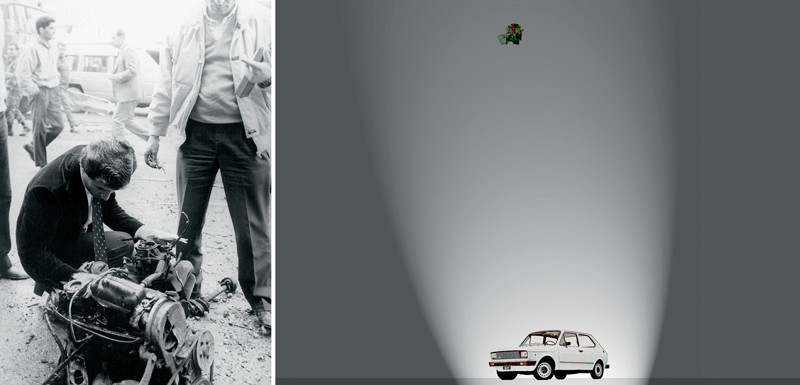

In a third piece, Title: Notebook Volume 38, Already Been in a Lake of Fire; File: AGA_Fakhouri; Date: 1975–1991/1999, Raad, through his principal character, Dr. Fakhouri, investigates the subject of car bombs by producing a notebook that purports to study the 145 car bombings that occurred during the wars. Each page of the nine framed double pages excerpted from Fakhouri’s larger file shows an image of a car of the same model and colour as one used in a bombing. The photographs are clipped from magazines, pasted in a haphazard manner onto the pages, and surrounded by Arabic text that gives the date, place, and time of detonation; make, model and colour of the car/bomb; type of explosives, method of detonation, number of casualties, and, in some cases, even the diameter of the crater created by the bomb. Again, a surfeit of painstakingly gathered detail takes us farther away rather than closer to any kind of explanation for the motivation for this relentless violence.

The fourth work is a pair of approximately ten-second-long 8 mm films that are presented on side-by-side video monitors. Dr. Fakhouri is said to have carried two movie cameras with him everywhere, and on one he recorded a single frame of every doctor’s and dentist’s office sign that he saw. On the other he also recorded single frames, but of where he was at each of the many moments at which he thought that the civil wars were over. The pairing is surreal as, on both screens, images of the utmost banality blink by on the screens – one of office signage and the other of n’importe quoi, a record that manages to quantify phenomenal futility and, yet, express a stubborn hopefulness.

Raad’s strategies of factual over-determination, use of found photographs, and construction of fictional entities have a curious echo in the hyper-realist literature of German author W.G. Sebald (for example, in his books The Emigrants and Austerlitz). Raad’s use of these strategies has been discussed as a way of mounting a critique of attempts to rationalize historically what has often, in fact, been irrational behaviour of a monstrous order – images of which never appear in the exhibition. In spite of similarities in methodology, the motivations for their particular ways of working are inversions of one another. Raad’s highlighting of the quotidian manages to implicitly refer to an “absence” at the heart of his project while strategically avoiding its representation. Sebald’s work, however, seems meant to consciously supplant an absence through its representation – that is, the descriptive vacuum created by German authors who ignored the mundane realities of noncombatants in their postwar writings.

Raad infers that the historicizing impulse is inadequate in the face of the often random-seeming carnage and chaos that erupted for more than fifteen years in Lebanon. While facts can be collected ad nauseam, their accumulation does not in itself guarantee truth. In fact, Raad goes one step further. Seen from a deconstructivist perspective, he appears to posit that the binaries mentioned earlier – of memory and history and truth and fiction – can exist only because they partake of one another. It is for this reason that the point seems not to “understand” that the Atlas Group is a fiction but to grasp that no fiction can exist without some basis in truth and vice versa. And, hence, history’s aversion to memory and the undifferentiated space of the everyday. Even as Raad builds various degrees of distance into his work, the effect appears to be to allow the very nature of such a mode of thinking to be called into question. Ultimately, one senses that Raad’s strategies have resulted in “another way of telling” that tries to embody an awareness of the difficulties and discomfort of doing just that.

Vid Ingelevics is a Toronto-based artist, writer and independent curator. He teaches at the Ontario College of Art and Design.