[Spring 2005]

International Center for Photography, New York

17 September – 28 November 2004

From its earliest days, photography has been used to bear witness to acts of violence and inhumanity. Its strength lies in the power to capture events as they transpire, to cast these events in a mantle of truth, and to circulate this evidence. At the heart of this activity lies the photographer’s desire to provoke a response from the viewer. Seeing is believing. This effect can result in a call to act and promote change – or the shock value of what is presented can create paralysis.

In the same way that photography has been used throughout its history to document tumultuous events, it has responded to the photographer’s desire to connect with the action. In times of war, the lines between soldier and photographer are distorted, or at least blended, depending upon the context. Soldiers have been tasked with documenting their surroundings and those they encounter, for the purpose of bringing home images of places and people that the larger public might never otherwise have a chance to see. There are official, sanctioned images, and there are others that are made for private consumption, as tokens for collection and exchange. Thus captured, such images do more than prove that an individual has been a participant in events in a specific and sometimes exotic place. They mark rites of passage and elicit shared memories. They build bonds.

Often, it is only through the distancing effect of time that some images can be made in any way palatable to those who did not participate in the events. A critical context requires that time elapse. If the images are presented too soon after the events, or even while they continue to unfold, the experience can be simply too close for comfort.

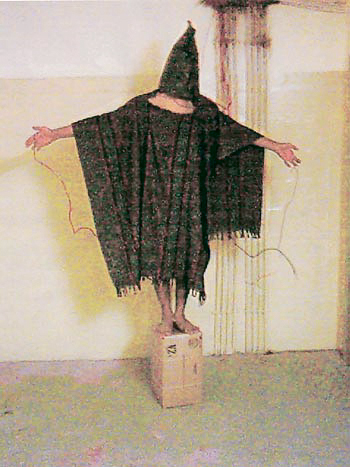

In the exhibition Inconvenient Evidence, the viewer is confronted by images that dwell somewhere within this sphere of circumstances. The installation features a selection of twenty digital photographs, tangible confirmation of the infamous degradation and torture by American soldiers of Iraqi prisoners held at Abu Ghraib prison. Neither were these photographs conceived of as a photo essay, nor are they the product of a documentary photographer’s assignment to cover a particularly newsworthy event. There is no pretext of objective distance. They were not taken in secret and smuggled out with the purpose of letting the world know about atrocities committed, by all indications with the knowledge and tacit approval of higher-ranking officers, although they do just that. Instead, according to the evidence of the digital time-stamp, they are the work of at least two of the soldiers who willingly and actively participated in the violence. During the brutality that transpired, the soldiers took photographs and made videos. They later transmitted images via camera phones and kept personal copies, whether as collateral insurance or, perhaps, as trophies.

Once the images began to circulate as digital files, there was no way to contain their proliferation, and they subsequently found their way onto Internet sites and finally into the mass media via broadcasts such as CBS’s 60 Minutes II, before being exhibited in their current context. It is estimated that hundreds of digital photographs were made during the course of events at the prison. When the Washington Post ran its coverage of the Abu Ghraib aftermath, the executive editor issued a statement in defence of his newspaper’s decision not to publish a large number of the photographs, stating that the content was simply too graphic for its readers.

In the context of the exhibition, the digital prints, presented without mats or frames, are mounted on the exhibition walls with pins. Nonetheless, a careful selection was made and each photograph is beautifully lit against the dark-grey walls of the small space – evidence that some careful design work went into the installation. Along with the two short essays in the publication that accompanies Inconvenient Evidence, the viewer is provided with a timeline of the incidents at the prison, spanning from when the U.S. military took over to the investigation of charges against one of the named perpetrators in the incidents, Private First Class Lynndie England.

The desire to record, commemorate, and, ultimately, share participatory acts of violence is by no means new territory for photography. Likewise, the photograph as fetish object remains a key theme in popular culture. These images share some characteristics with pornography: they exploit the powerless and offer up proof that accepted modes of conduct have been transgressed. Both the content and the desire to explore the dissemination of such images evoke undeniable parallels with the recent presentation of historical postcard images at the New York Historical Society in the travelling exhibition Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America.

Inconvenient Evidence is presented in conjunction with two exhibitions of documentary photography: Looking at LIFE, selections from a gift to the International Center of Photography by the Time Inc. Picture Collection of over one thousand prints from the magazine’s archive, and JKF for President: Photographs by Cornell Capa, in memory of the ICP’s founding director. This juxtaposition is an interesting play of contrasts in terms of the time periods, the photographers’ intentions, the modes of dispersal for their photographs, and the reception by the public of what is presented.

The exhibition is troubling on a number of levels. First and foremost, the content of the images is extremely disturbing. In spite of the fact that the Abu Ghraib images are so pervasive in the mass media as to have become ubiquitous to a desensitized public, when each image is isolated in the context of an exhibition the museum effect takes over, rendering the photographs new and shocking once again. Viewers are asked to slow down and to look closely at something that they may be aware has happened, but that in all likelihood they rather consciously ignore. But evidence is inconvenient precisely because it gets in the way of complacency. We wonder what other caches of photographs are lurking beyond the borders of our daily lives. Like the photographs in Inconvenient Evidence, they may have been created for a purpose in complete contradiction with how they will be judged.

Johanna Mizgala is the Curator of exhibitions for the Portrait Gallery of Canada, opening in 2007.