[Spring 2005]

Subject movement is minimal and unpredictable, defined as it is by the capriciousness of the natural phenomena pictured, and yet, paradoxically, the long, uncut take makes time seem unnatural and delayed. As such, Denniston’s ‘stills’ give rise to a complex and contradictory temporal experience, positioning the viewer somewhere between the long, eternal movements of natural history and the sense of urgency that attends modern life.

by Cheryl Sourkes

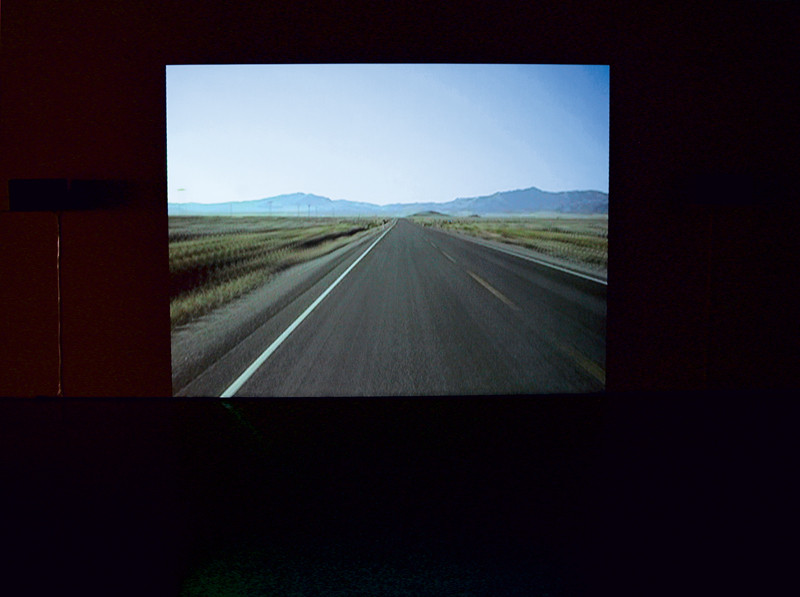

Normally, photographs and film/video engender different types of capture and different modes of reception from one another. Stan Denniston came to a juncture in his practice where he wanted to explore a boundary zone between these genres.

In 1997-98, he had produced a series of large inkjet prints called billboards – diptychs pairing American cold–war-era civil-defence sirens and skies. After contemplating billboards, Denniston decided that he would shoot his next body of work with a video camera to add the dimension of duration to the viewer’s experience. Because he approached time-based technology with the sensibility that he had developed as a still photographer, these works are a hybrid product that resides somewhere between the two forms. He made this confluence apparent by naming the work stills.

In the first manifestation of stills, in 1998-99, Denniston utilized a stationary video camera to shoot the type of air-raid siren first seen in billboards. The second manifestation of stills (2001) used this same approach to natural wonders. Although these pieces were composed as traditional photographs might be, subtle movement rewards the patient viewer’s attention. Because Denniston shoots in the natural world, unplanned events manifest – a cloud morphs, the light alters, a moth or a person meanders through the picture plane, and so on. There are no pans, zooms, or edits in stills, only minor changes uncontrolled by any person’s will. These fixed-focus movies create a sense of perpetual immanence and, at the same time, perpetual distance.

But not only is Denniston’s technical approach situated in a liminal region; his subject matter falls between categories as well. He films natural forms with cultural overtones, such as hoodoos and balanced rocks, or cultural forms that time has naturalized, such as the defunct and rusting civil-defence sirens.

Stills may be located within the lineage of structuralist films, including those made by such seminal artists as Andy Warhol, Jan Dibbets, and Michael Snow. However, while Warhol made use of looped footage to create protracted movies, such as Sleep and Empire, Denniston’s stills unfold in real time. And while Warhol’s and Snow’s films tend to be exhibited in the context of art-house cinema, Denniston’s works are mounted on television monitors within the gallery context, where viewers are free to choose their own length of engagement with each piece.

Traditionally, photographs and movies have enjoyed different conventions of reception. The photograph tends to be first perceived as a whole and later scanned for detail. When the viewer’s fascination wavers, the experience is complete. On the other hand, a single-channel work is normally seen from beginning to end. The eye tracks movement rather than detail. The viewer synthesizes the whole only when the piece is over. Reception of stills problematizes these viewing conventions. The single-channel presentation of Denniston’s almost-still movies creates a convergence of form and content that destabilizes reception habits. It challenges the viewer to find new viewing rhythms while opening up a different type of attention. There is no one story, no one emotion leading the viewer, as one might find in other contemporary or more popular film and video experiences. Rather, this work tends to deconstruct the viewing experience, opening through narrative space into contemplation and speculation.

According to Jonathan Crary’s1 reading of Anti-Oedipus, Deleuze and Guattari propose, “Modernization is the process by which capitalism uproots and makes mobile that which is grounded, clears away or obliterates that which impedes circulation, and makes exchangeable what is singular.” Denniston’s work resists this tendency by impeding the process of turning its subjects into mobile signs. His lens’s long, nervous gaze re-presents his material as uncanny and obdurate. These contrary, hybrid subjects passively resist mobility and circulation. The longer the viewer chooses to stay with the movies, the more their subjects recoil into their inhuman indifference. The viewer’s sense of time and perception becomes mobilized in a way that thwarts capitalism’s desire to transform the world and all its contents into circulating signs ripe for manipulation and consumption. In the end it is phenomena, resistance, and mystery that cleave.

Stan Denniston has exhibited extensively in Canada and Europe. He began his NOMo video project in 1997, inspired and mentored by Montreal artist Jacques Perron. In 2003–2004, he worked as cinematographer on Peter Lynch’s feature documentary A Whale of a Tale. Denniston is represented by Olga Korper Gallery, Toronto, and by Galerie les filles du calvaire, Paris and Brussels.

Canadian artist Cheryl Sourkes has been based in Toronto since 1993. Her work has been exhibited extensively throughout Canada, as well as in the United States, France, Italy, Great Britain, Germany, and Belgium. She has contributed to or had her work featured in many publications, including Geist, ANGELAKI, Capital Culture, new formations, TESSERA, Public, Blackflash, and The Zone of Conventional Practice & Other Real Stories. She has also curated extensively.