[Summer 2005]

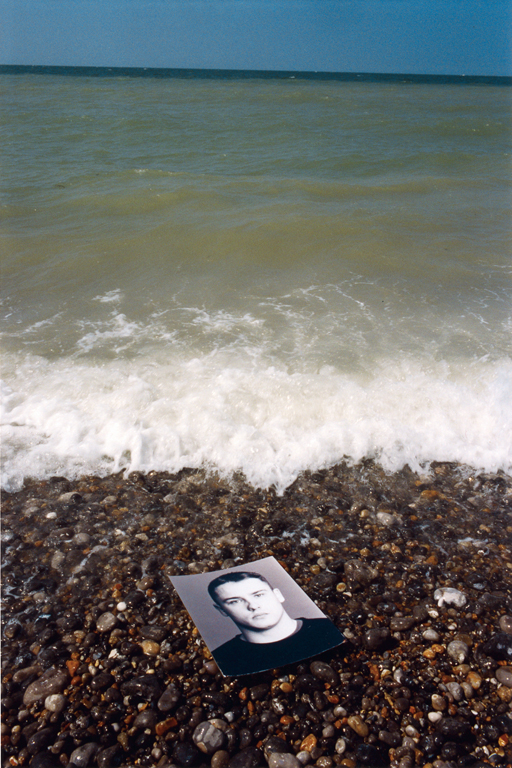

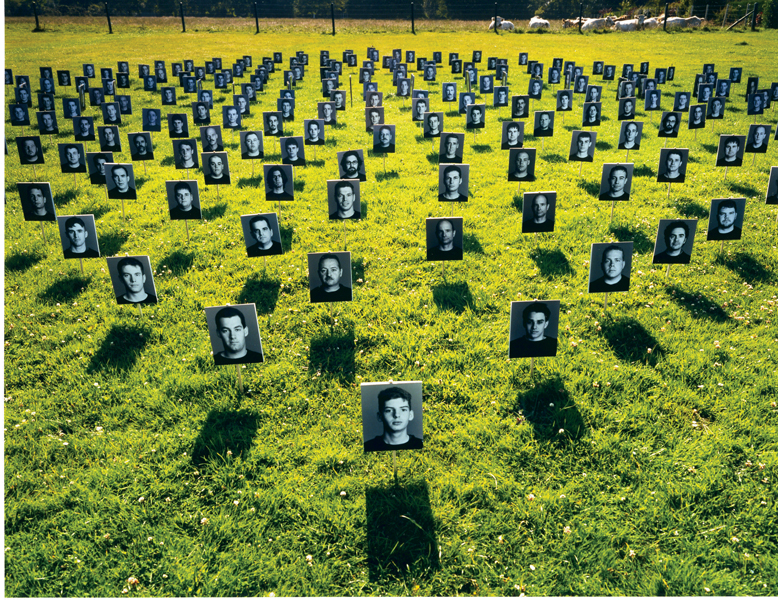

It was preceded by Jubilee, an installation in two parts referred to as “an ephemeral monument” and “a cemetery of images”, in which nine hundred and thirteen photographs were propped up in the stones of the beach to be borne away by the sea and installed on sticks to represent a war cemetery, just beside the chapel. 913, the film, retraces the making of these works while recalling the story of this event.

by Gary Michael Dault

The aftermath of conflict lives forever. Battles end, armies fall or prevail, lives are lost or spared, history stops, adjusts itself, and groans forward again into time. But memory remains – as palpable as the silence in which it is most often embodied.

Bertrand Carrière’s film 913, released in 2004, sixty-two years after the event it memorializes, incarnates the memory and the meaning – or the desperate meaninglessness – of the disastrous Dieppe raid of August 19, 1942; nine hours of ill-planned military madness in which over six thousand Allied soldiers, five thousand of them Canadians, conducted a massively ill-fated operation – ironically named Operation Jubilee – designed to wrest a northern European foothold from the German army by means of a frontal attack on the Normandy beachhead near the seaside resort town of Dieppe.

At sunrise on that dire August morning, the sea-borne assault troops, intending merely to launch a sharply coordinated surprise attack on the German installations (shortly after which they were to retreat again with the high tide), threw themselves at the chalk cliffs of Normandy, which bristled with entrenched German gun emplacements. The Allied soldiers – supported by eight destroyers and seventy-four air squadrons, eight of which belonged to the RCAF – attacked from the sea, and were resolutely mown down by the guns of the German army, an army fully alerted, as it turned out, to this so-called surprise attack. By nine o’clock, two hours after the battle had begun, it was clear that the engagement had become little more than a slaughter. Of the Canadian troops at Dieppe, 3,367 became casualties. Almost two thousand of the men were taken prisoner of war. And 913 died – thus the title of the Carrière film.

The film commemorates these Canadian soldiers fallen at Dieppe in a most arresting and affecting way. Carrière says in the film that he wanted to “leave something tacit” as a way of remembering Dieppe. This he did by effecting an installation at the site in 2002 – the work was called Jubilee, after the military operation – that entailed the conceiving of what the artist refers to in the film as “an ephemeral monument, a cemetery of images.”

The installation explored what Carrière rather cannily identifies in the film as “the links between photography and water” (the molecular chemistry of the photographic image, its development in fluid, its baptismal washing in water) as well as, implicitly, the links between the nature of the photographic image and, in this case, the specifics of the photographic subject – doomed young soldiers released by the thousands from landing crafts, sprung from the sea only to be mown down in the water and on the beaches, a horrifying and demonically compressed replaying of the quintessential act of evolution – in reverse.

In order to construct Jubilee, Carrière first photographed Canadian soldiers – 913 of them – making black-and-white, head-and-shoulders portraits of the faces of young men no older than their forebears who were killed at Dieppe over a half-century earlier (it is one of the many disturbing moments in the film that none of these young men appeared to have a clue as to what Dieppe was or what it meant).

These photographic portraits were then erected on the beach at Dieppe, Carrière and a squad of assistants diligently working to prop up each portrait in the loose stones of the shore so that, in the end, they formed a strange and stirring amphitheatre-shaped aggregation of implacable faces waiting silently in the endless outwash of historical meaning. There was only one chance to make the arrangement and to get it right (“913 portraits on the beach on a single low tide and no wind”), for it was to be the fulfilment of the work, its dénouement, that the incoming tide would soon dislodge each photo and carry it out to sea. And so it was to be. In a single directorial action linking the past and the present, Carrière marshals what he calls “these silent faces now come to die again on this same beach,” and it is poignant to watch them, in the film, as the waves take the photographs, one by one, and bear them away.

This large-scale curatorial act became what Carrière calls “a way to put a face to history.” And it did that consummately well. But the historical moment of the Dieppe raid was searing, convulsive, and bounded. And history has a surround, as well as an epicentre.

The photographs that comprise Carrière’s Caux (Chalk), made, for the most part, in 2003, after the staging of Jubilee, explore the environment that cradled the cataclysm. The photographs are of the beaches themselves, of their soft, moss-tinctured stones, stones oxidizing through time, burning in infinite slowness with nature’s rust, of the sea wall, the barbed wire; of the residual – the shell-broken structures of combat, the tide pools, the massive boulders, and the façades of the chalk cliffs themselves (the hollows that were gun emplacements dark now like empty eye sockets in the skulls of rock); of the whole bruised and aching environment of war, still slowly healing in the grey, ocean-overcast air of Normandy sixty years later.

“Mon intérêt s’est fixé sur cet endroit où l’histoire sombre des lieux s’oppose constamment à la lumière des ciels côtiers,” writes Carrière about Caux. “L’espace y est ouvert, vaste et lumineux. J’utilise l’image photographique pour explorer la mémoire profonde de cette région et la topographie singulière de ce littoral. J’interroge les aspects sourds, parfois silencieux de l’histoire, inscrits dans le paysage.”

The Caux photographs are timeless in the sense that they limn a landscape, an “inscribed” landscape, that seems to face both forward and backward, Janus-like, at the same time. How strange it is now to look at a painting such as J. W. Morrice’s Dieppe from 1906, in which the sea wall separates an assortment of sunlit couples, chatting under striped umbrellas, from the deep cold blue of the North Atlantic. Or, for that matter, to gaze upon J. M. W. Turner’s The Harbour of Dieppe from 1826, now in the Frick Museum, a painting widely regarded at the time as “a splendid piece of falsehood” because of the way the golden luminosity of the picture seemed untrue to the cloudy imperatives of a northern port. It is not possible to see these paintings now without knowing what is to come. And to see them, therefore, as a part of what Maurice Blanchot has called “the language of awaiting.”

By contrast, Carrière’s Caux photographs embody a language of oceanic recollection, a deep discourse of memory – which is similar in its intensity to a language of awaiting, but differently valenced. Carrière’s Dieppe photographs are also about waiting – but about waiting as a means of accumulating understanding. As such, they “keep watch over absent meaning.”1

There is an insistently elegiac quality in most of the Caux photographs, which is the result both of the grey, veiling light of the North Atlantic, with its suspended luminosity, and of Carrière’s exquisite responsiveness to the burden of meaning borne by recollection. Here, at the site of a profoundly misbegotten military action, the fallout of its folly has imbued the very landscape with an eternally lingering aura of grief and regret – embodied in Carrière’s dark rocks stained by time as if by dried blood, in his softening stone steps that lead nowhere, in his broken windows, his coils of purposeless chain, his wanton grasses, his cold breaking waves. In this place, writes Carrière, “Profondément minéral, sanctuaire d’une mémoire douloureuse, l’histoire y semble en suspens, pétrifiée dans les espaces.”

The Caux photographs are the long, eternal corrective to the sharp pang visited upon us by the sight of his 913 portraits washing out to sea. Those photographs are gone. These remain.

Bertrand Carrière’s photographic work is characterized by a search for intimacy, availability of the gaze, and a constant capacity to have restive signs emerge into the visible. His works are arranged in serial groups that explore memory and history inscribed in the landscape. His work has been exhibited in Quebec, Canada, and Europe. Born in Ottawa in 1957 and currently living in Longueuil, he is represented in Montreal by Galerie Simon Blais and in Toronto by the Stephen Bulger Gallery, and his works are distributed by the VU Agency in Paris.

Toronto writer, art critic, and painter Gary Michael Dault is the author or co-author of ten books, including Cells of Ourselves (with artist Tony Urquhart), and two recent books of poetry, In Smoke and Odes and Removals. His weekly art review column appears each Saturday in The Globe & Mail. Dault’s Alice in the Orchestra (with composer Gene Di Novi) is to be performed by the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra in September of 2006.