[Fall 2005]

Sourkes’s current practice is not one of making images so much as it is one of selecting and editing from the thousands of screen grabs that she has collected. Among these images, some places are immediately recognizable and many others are not notable; they could be virtually anywhere, rendering the technologically enabled world as a relatively undifferentiated and easily legible universe.

by Jessica Wyman

Perusing webcams online is perhaps, at least superficially, far less interesting than one might imagine. Tracking down streaming images from all over the world is a rather mechanical task, and the images and locations that are found with varying degrees of ease seem to blur together at some point, breeding a kind of armchair-tourism ennui.

After all, where can’t one go with speed and relative ease, sitting in front of a computer monitor?

And yet . . . there is a wonderment about surfing webcams that is in some way quaint, old-fashioned. For travelling the world this way, picking a place out of a hat and finding that one can see it, almost no matter how remote, at any time of day or night, does seem at least a little miraculous. And when the miraculousness of the technology has been accommodated, other questions arise: Who sites these cams? Who watches these cams? Why are they considered to be useful? What does it say about our society that in our desire to watch others, we yield ourselves to the camera, to hundreds of cameras, every day, sometimes voluntarily and in our own homes? These questions, unlike the repetitiveness of searching for and finding the cams themselves, are anything but mechanical, and they yield anything but simple and resolute answers.

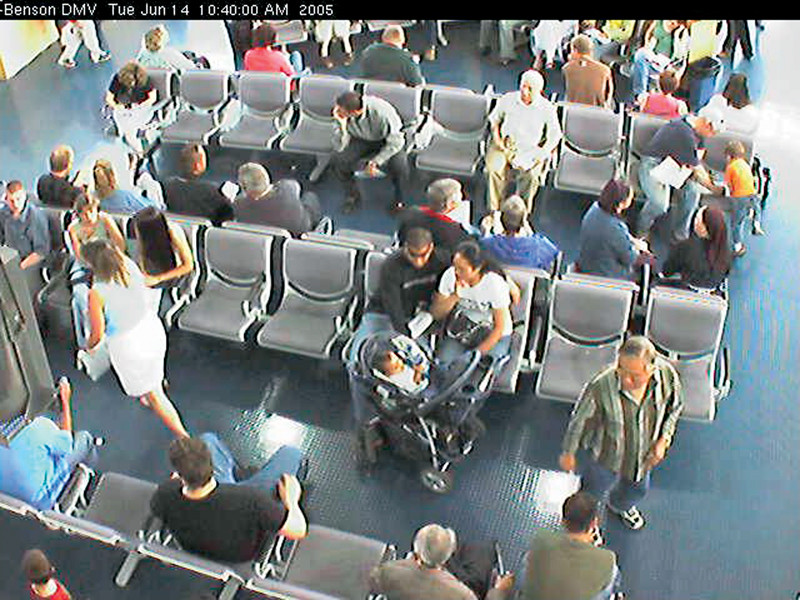

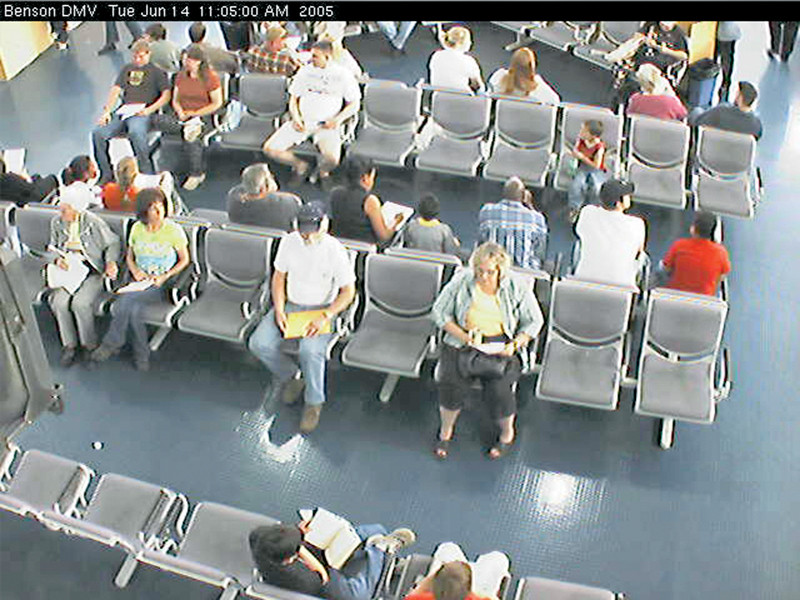

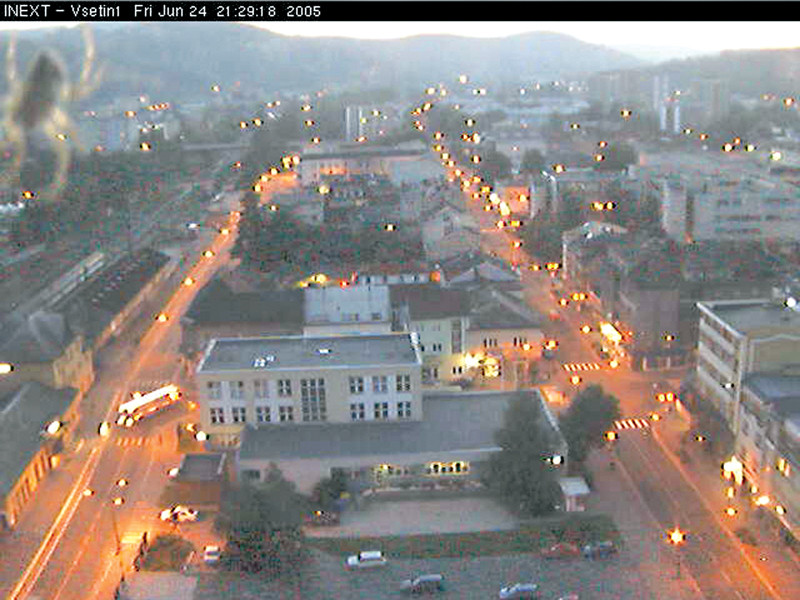

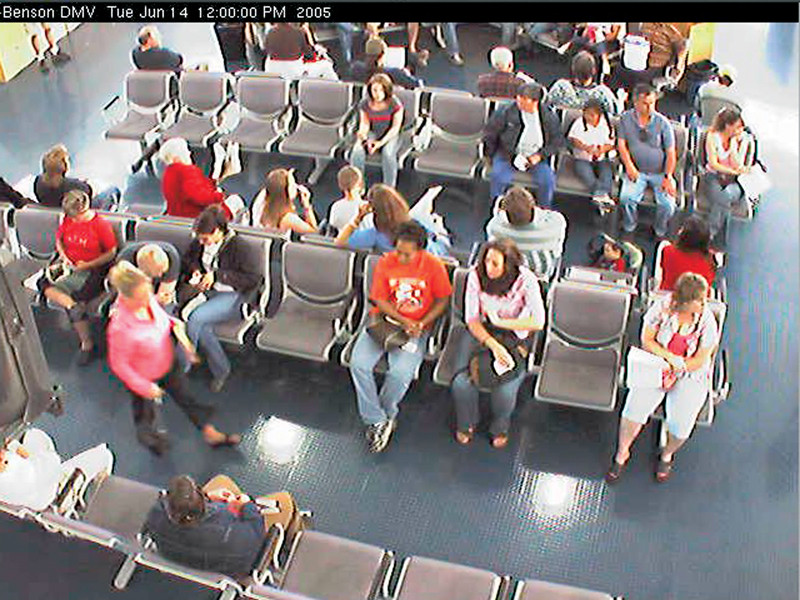

Cheryl Sourkes has been surfing and capturing webcam images for several years, and her work serves to articulate for viewers some of the ponderous questions that emerge in seeing the world differently through this particular technology. Sourkes’s current practice is not one of making images so much as it is one of selecting and editing from the thousands of screen grabs that she has collected, organizing images into such categories as “Locations” (images of particular geographical sites), “Interference” (images in which something, such as precipitation or insects, interferes with the clarity or totality of the image), “Interior” (interior images of businesses, homes, places of leisure), “Convenience Cams” (in which the artist has asked a friend to make a webcam appearance for her), and others. Among these images, some are immediately recognizable – Times Square, the Eiffel Tower – and so many others are not notable; they could be virtually anywhere, rendering the technologically enabled world as a relatively undifferentiated and easily legible universe.

In editing these images and representing them, Sourkes’s work operates somehow not as simple voyeurism, though certainly much of the imagery that is available for viewing via webcam is ready-made for the voyeur. In her categorization of what she finds on the Web, Sourkes serves as an image filter, capturing pictures of pictures, presenting images that have the same resolution and flatness as in their original capture (and the engagement with such images and forms of circulation does raise a multitude of questions about the nature of originality), freezing the moment at which the cam captures the movement of the subject (who may or may not be aware that his or her image is being captured at all).

In thinking through the origin of the image, and maybe in wondering about who the “real” maker of these images might be, it becomes clear that working with webcam imagery raises many questions about how we understand originality and visibility as facets of knowledge. In the instance of the webcam, these epistemological questions seem to hang somewhere between the real and the virtual, as do the images themselves, for there does not yet seem to exist a set of tools with which to make satisfactory sense of webcam signification as more than simple voyeurism, exhibitionism, or technology of surveillance.

Just as none of voyeurism, exhibitionism, or surveillance should be considered simple in itself, the technology of the webcam that enables all of these proclivities in the online universe is simultaneously simple and anything but. Describing the mechanical processes by which images are captured and disseminated on the Web does nothing to address the ways in which such tools speak of the depth of contemporary culture’s dysphoria when it comes to the production and dissemination of images of everyday life and living.

In Sourkes’s Interior series, the vast majority of images depict scenes of utter banality, captured by cameras in places that are unlikely to produce anything that most viewers would deem worthy of record. While the “Chapel Cam” works depict, in both still and time-lapse-video form, couples marrying in a Las Vegas wedding chapel – clearly a rite of passage, even if under the most fascinatingly hackneyed circumstances – webcams in barber shops, radio stations, automotive-supply shops, banks, and people’s living rooms or office spaces are unlikely to yield great spectacle – not least because so many of the people occupying these places are either unaware of the camera’s presence or have accommodated it to such a degree that they are oblivious to its all-seeing (and all-transmitting) eye.

What is it, then, that makes us want to watch? Perhaps it is the faux intimacy of online surveillance, the very opening up of a life or a location to scrutiny of its ordinariness. In certain cases, such as that of Jennifer Ringley (she of the famed and former www.jennicam.org), the very ordinariness of an individual’s quotidian reality takes on an aura of the spectacular as it becomes available for viewing, sliding easily into a form of reality television, a similar, if more widely discussed and more thoroughly produced, phenomenon. Webcams seem to circulate, for the most part, images of banality and shame rather than of the fame, beauty, and success with which our society is reputed to be so obsessed. How does this flaunting of imperfection relate to our ostensible desire to obtain perfection? What of the “nothing” that takes place in front of the webcam lens?

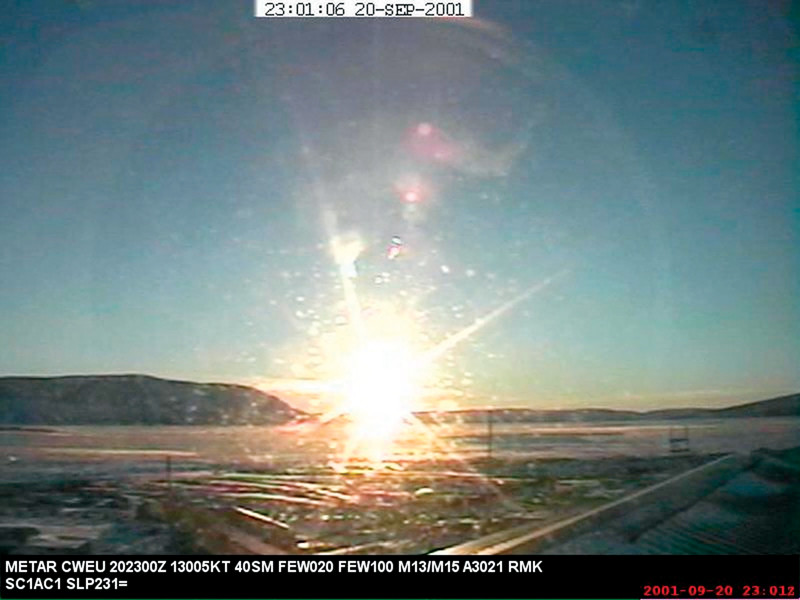

In the Interference series, what happens in front of the lens is interrupted by what happens on it, shifting the locus of interest to the space that announces itself as exactly the blur between visuality and televisuality. In these images, light reflections, weather conditions, or the tenacity of an insect interfere with the exteriority of the image, insisting on the webcam lens as a presence in the image and undermining the authority or neutrality of the surveilling device. While these interruptions cannot be claimed as insertions of any particular positionality, what they do is serve as aspects of incontrovertible reality in the context of images that can be so easily dissociated from the reality that produced them and that they reflect.

Perhaps, ultimately, what Sourkes illuminates with this work is the degree of reality that we consider to be separating us from what is represented in her webcam images. What we see through her work is an aspect of reality to which we may give little thought in its application to ourselves: how do we look from afar as we cross the street? How often are we seen in a day through such devices as these?

Or perhaps, rather than using this work to further insert and insist upon social and cultural divisions, the intention is to connect “‘local gazes’ with the global community,”1 to understand that at the very least we can and do all see the same things when we look at one another, that banality is engaging simply because it is the reality that pertains to all of us in our non-celebrity imperfection. Perhaps, for all of the complications of viewership and authorship, of who is seen and by whom, the frontier that Sourkes crosses with this work is that of realness – that which we already have but which is made new, again, by its mediated lack of mediation.

For the last five years, Toronto-based artist and curator Cheryl Sourkes has used webcam-generated source material for her photographic stills and animated sequences. Her work has been exhibited extensively throughout Canada, as well as in the United States and Europe. She has contributed to or had her work featured in many publications, including Geist, ANGELAKI, Capital Culture, new formations, TESSERA, Public, Blackflash, and The Zone of Conventional Practice & Other Real Stories.

Jessica Wyman is a curator, writer, and art historian who teaches in the Faculty of Liberal Studies at the Ontario College of Art and Design. Her current work considers the subjects of performance art historiography and contemporary art and practices of resistance. She is a member of the editorial committee of FUSE magazine, and she received the Emerging Curator Award in Toronto’s 2004 Untitled Art Awards.