[Fall 2005]

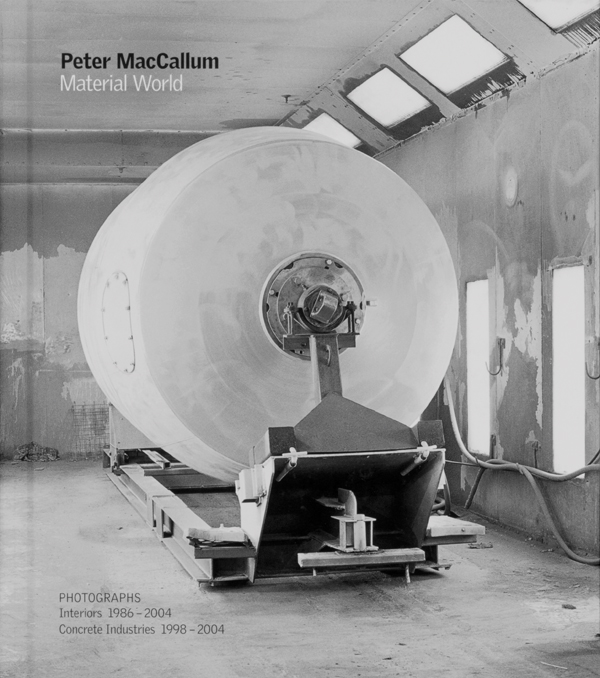

Peter MacCallum:Material World

YYZ Books and Museum London

2004

Since the late 1960s, Toronto photographer Peter MacCallum has been devoting a great deal of his time to documenting the work of other visual artists. It has been a long, exacting sojourn in alternate sensibilities that might well have exhausted anyone less determined than MacCallum to pursue his own photographic interests in parallel to his commercial tasks.

MacCallum’s major subject, over the past twenty years, has been Toronto’s retail, industrial, and construction history and, especially during the last decade, documenting the concrete industry in Ontario. The shape of this photographic progress has recently been incarnated in a handsome book called Material World, co-published by YYZ Books (the publishing wing of Toronto’s YYZ Artists’ Outlet) and Museum London, which hosted a major exhibition of MacCallum’s photographs during the winter of 2004.

The book is divided into two sections: the first part, Interiors, 1986–2004, offers a kind of archaeology of the present – or at least, of the very recent past. Here, the photographs document the old textile shops on Toronto’s Queen Street West, with their teeming clutter, and the visual cacophony of the old family-run hardware stores – both of which being businesses that are now, inevitably, disappearing. As MacCallum notes in his foreword to the book, “The great architectural photographer Robert Polidori has pointed out that ‘the room’ as a photographic subject can be a portrait both of its individual human occupant and of a society. In my interior photography, the emphasis is on the social function of anonymous technical spaces. In some of these interiors, the contents have come to dominate the architecture over time. In others, accumulated grime, wear and tear have softened and blurred its outlines, destroying its purity.”

A second focus of the book’s Interiors section is the sweaty infernos sequestered within such small-scale industrial enterprises as the National Rubber factory (1995–96) and the Wickett and Craig Tannery (1989–90), the factory featured in Michael Ondaatje’s 1987 novel In the Skin of a Lion, and which was finally closed by the city in 1990. Unlike most of MacCallum’s subsequent photographs, which attain their sometimes considerable drama (which often approaches the epic mystery of Piranesi’s Carceri) by means of limning the complex industrial environment without recourse to the personnel therein, these gritty factory photos portray not only the grim, febrile world of industrial process but quite often show the workers labouring in what can still be seen as William Blake’s “dark, satanic mills,” the kind of environments that we continue to think of as Dickensian. Globe & Mail columnist Russell Smith, who provides one of the four interpretive essays included in the book, draws attention to “the archaic quality to the factories to which MacCallum has been drawn” and notes, “Leather, rubber, cement – these are dumbly industrial products we continue to depend on, even in the cybernetic age; they are resistant to digitalization.”

MacCallum himself is “resistant to digitalization”; he is among the most deliberate and exacting of artists, carefully making his “straight photographs” (that is, without employing digital correctives or Photoshop enhancement of any kind) from large-size negatives, which he (naturally) prints himself. His photographs are everywhere imbued with an exquisite technical care and an elegant sense of quiet deliberation. And this is especially true of the photographs making up the second part of the book: the Concrete Industries photos (1998–2004).

Having begun, as MacCallum explains to fellow photographer Blake Fitzpatrick in an interview included in the book, with individual sites in Toronto “that were related to concrete production or use, or recycling” and then branching out “to photograph limestone quarries and cement powder manufacturing plants,” MacCallum eventually began moving beyond the city to document the province’s cement plants, many of which had fallen into disuse and, thus, disrepair – sites that in some cases were little more than ruins. As I noted in a discussion of these photographs in The Globe & Mail, “It is the documenting of these outcroppings of dead industry, in particular, that MacCallum’s photographs are positioned where historical research, social history and the pleasures of pure visuality intersect.”

Almost everyone who has written about MacCallum’s Concrete Industries photographs has eventually found it necessary to discuss the juxtaposition, and even the congruence, of the documentary objectivity (or apparent objectivity) in his work and the luminescent beauty of his prints. As I wrote last year in the Globe, “Crisp, lean, subtly composed and aglow from within, as if the pearlescent cement dust that floats through the photographs were made up of particles of airborne light, MacCallum’s Concrete Industries photographs are effulgent with radiance – albeit in the service of documentary truth.”

What appears to be a potential conflict of methods and meanings, however, in fact lends MacCallum’s photographs much of their distinction. He writes, perhaps a little bemusedly, in his foreword to the book, “There is often a somewhat comical misunderstanding between myself and those who are interested in my photographs as art. I want to talk about the subject all the time, while they would prefer to hear how my personal approach led me to represent the subject in a particular way.” MacCallum cheerfully recognizes that the viewers of his exhibitions “are not completely uninterested in knowing the difference between chrome tanning and vegetable tanning in the manufacture of leather, or the distinction made in the building industry between cement and concrete, or how the activated sludge process is used to clean water in a sewage treatment plant.” Indeed, he almost grudgingly allows that “they are also interested in the light, form and texture of my photographs, characteristics which I consider to be dictated by the nature of the subject.”

And yet one feels that MacCallum is being just a little ingenuous here. He has a superb eye that subtly captures the delicacies of form and the creative vagaries of light, and, although he appears to regard it with some suspicion, he is remarkably attuned to the impress of what we may as well have the courage to call beauty in his own prints and in the art of others. In the best of his Concrete Industries photographs, for example – and it is difficult to decide which these might be, since his level of photographic excellence is invariably high and consistent – there is a sense of the anthropomorphic, entrail-like interiority of a factory complex, with its slices and layers of increasing distance lending a mythopoeic, Leviathan-like majesty to what can be interpreted both as a document clarifying a process or its site (see, for example, his Finishing Mill Department, St. Marys Cement, Bowmanville, Ontario, 1999, or his [perhaps inadvertently] psycho-sexualized Interior of Rotary Kiln During Brick Repairs at the same plant and same time) and, simultaneously, as a lambent ode to the wonders of the built industrial environment, the honouring of the exoskeleton-like extrapolation of our roles as man-the-maker. It is not to accuse MacCallum of inconsistency, but merely to underscore the fact of what Walt Whitman called the “multitudes” that inhabit us all, to note that the photographer, peerless recorder of external reality that he is, has admitted (to Blake Fitzpatrick in Material World), “I’m not a historian, I’m an artist.” At the same time, a good photograph, he observes, “has to stand for what cannot be shown, because you can’t show everything unless you want it to be in a non-artistic way.” And I cannot imagine Peter MacCallum, even at his most archivally acute, doing that.

Toronto writer, art critic, and painter Gary Michael Dault is the author or co-author of ten books. His art review column appears each Saturday in The Globe & Mail.