[Winter 2005-2006]

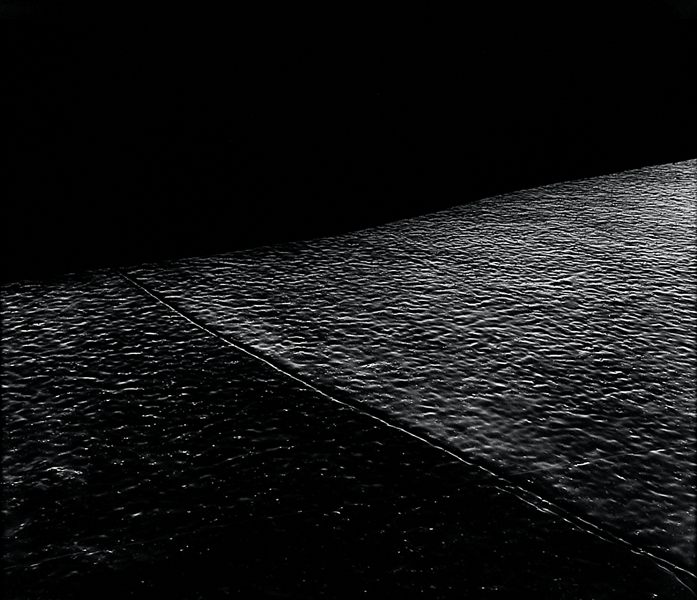

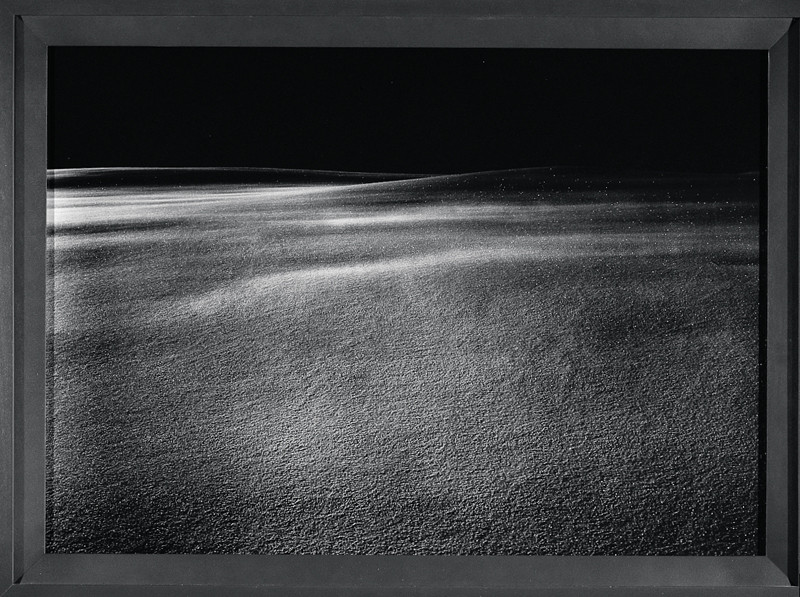

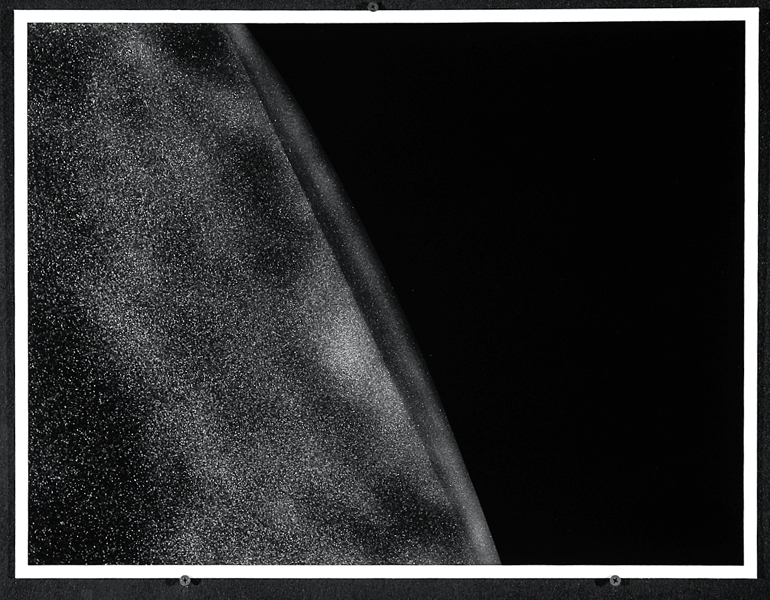

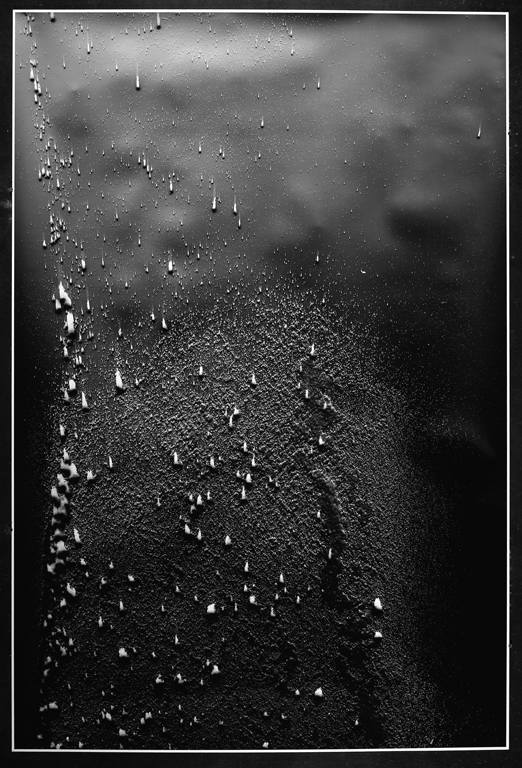

Whether rain and snowfalls registering at night on handmade photograms (Teeming), the evidentiary bioluminescence of fireflies caught on photographic flypaper in the dead of night as they seek to couple and multiply (Higher Ground), or snow-covered landscapes photographed directly in strong sunlight (Rising), his work demarcates the fine line between the visible and the invisible, what is seen and what is unseen, the perceptible and the imperceptible.

by James D.Campbell

Seeing light is a metaphor for seeing the invisible in the visible, for detecting the fragile imaginal garment that holds our planet and all existence together. Once we have learned to see light, surely everything else will follow. — Arthur Zajonc1

We work for that part of our vision which is uncompleted. — Frederick Sommer2

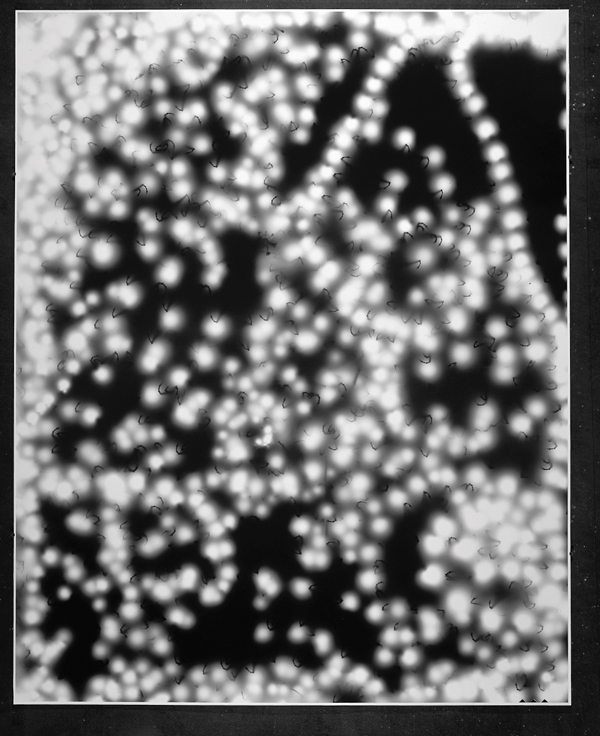

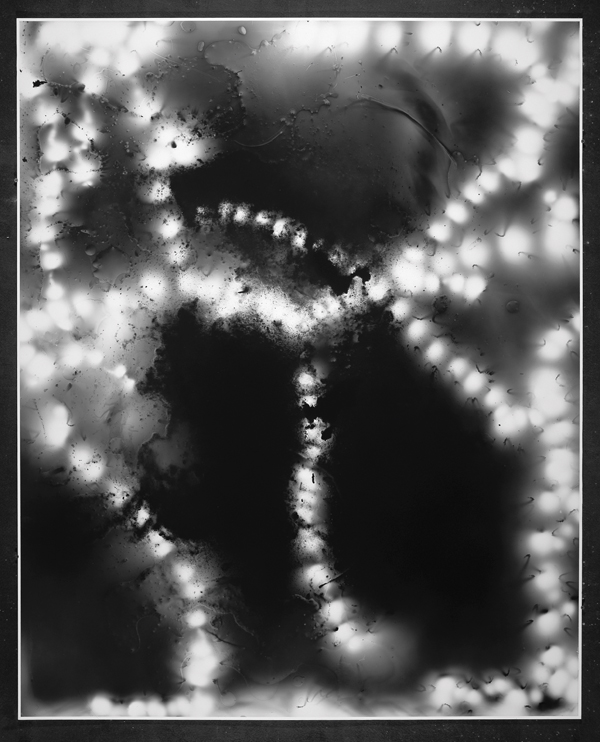

Fireflies have a way of lighting up the night with their flashings, making us nostalgic for those moments in early youth when, come a sultry summer evening, they would superimpose on the night sky their own incandescent constellations that were wont to blink on and off incessantly, enrapturing the eye. The transient spectacle afforded by those peripatetic versions of celestial maps never failed to induce in us a welcome state of startled wonder. Fireflies light up Michael Flomen’s photographic work as well, and to equally exalting effect. He freezes the movement and the form of a firefly on photographic paper with alacrity, and creates a seductive fantasia of the heavenly firmament, with web-like traceries of pale fire left on the face of the deep.

In his large-format, exquisitely printed, and beautifully framed black-and-white photographs, Flomen captivates our optic and draws it toward what is hidden in plain sight, sequestered between the darkness and the light. He draws our attention to the liminal spaces that exist between tenses, conditions of matter, and even states of being. By making visible parts of a world previously unseen, and even unsuspected by many of us, he places us squarely on the threshold of an ineffable visual space that dwarfs, seduces – and promises to swallow us whole.

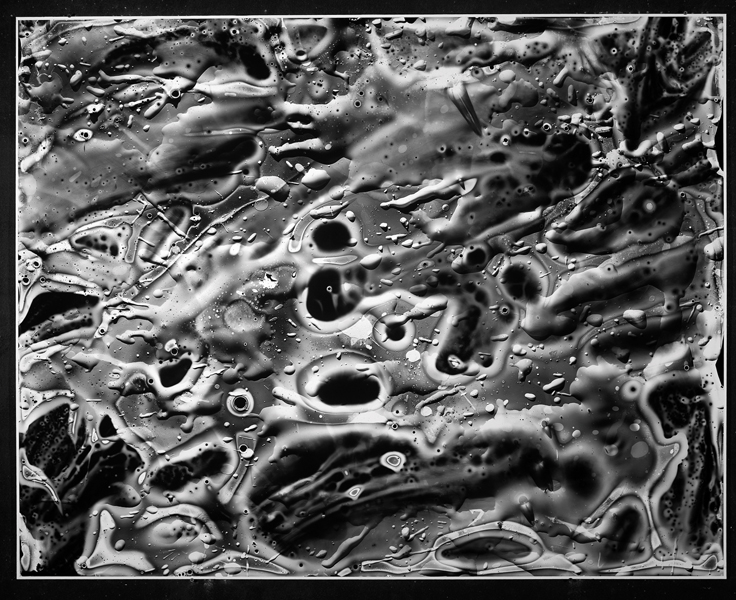

We become like little children again, beggars on the precipice of infinity, as we find ourselves standing on the doorstep of the Milky Way galaxy, say, or squarely ensconced upon a vast ice-age glacier in summer clothing, Book of Genesis close at hand. Whether it be the mating dance of fireflies, or the metaphorical interaction of “oil” and “water,” or the seeming birth of galaxies somewhere strangely other in the night sky, we are transported to an arresting elsewhere that remains the everlasting promise of Flomen’s most uncompromising of abstractions.

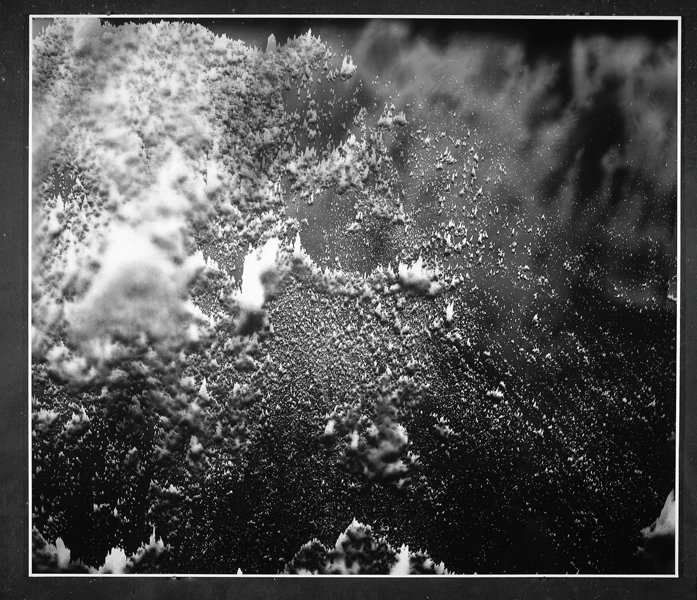

Flomen shows series of photograms that effortlessly demonstrated once again just how wide the metaphoric reach of his art is. It is all the more remarkable given that he wields no camera, no state-of-the-art digital imaging equipment or magical studio stunts or tricks, only the most inquiring of minds and a savant’s take on the history of photography, both technical and aesthetic, mastered over long years. His photograms, using the unlikeliest of source imagery in order to seize upon those moments in and out of time that seem fraught with all the surreal indeterminacy and ambiguity of the dream, open up new terrain for photographic practice at a time when the digital image enjoys uncontested hegemony. One such work exhibited at Bain Mathieu, and auspiciously titled Breakthrough (2005), embodies a gnomic topography that suggests a dust storm in some mysterious Sahara of the mind. It is a welcome leech on the imagination of the viewer.

For over three decades, Flomen has tried, as the American poet Elizabeth Bishop once said, to “look and look our infant sight away.” In her magnificent poem “Over 2,000 Illustrations and a Complete Concordance,” she articulated her desire to achieve the truth of seeing without the old censure or taxonomic restriction as she compared steel-etched illustrations of the Holy Land found in a Bible with a random catalogue of her travels.3 The intensity of said regard would mean, for Michael Flomen, putting paid to the jadedness of the old ingrained, literalist photographic vision and reacquiring a pure, unadulterated optic on the full array of things seen. This is precisely what he has achieved in his extensive body of photographic work – redeeming photography of the historicist and revisionist nature of its project and rendering it new and vital once again by seizing on the unlikeliest possible source imagery – and relinquishing, for the most part, the camera and its lenses and the “lazy eye” of old ways of thinking.

Michael Flomen’s black-and-white photographs and photograms resemble light-inflected shadowlands of lunar landscapes, or Hubble-like images of previously unknown galactic clusters being birthed, or forms barely glimpsed under the surface of desert sands worn down by relentless attrition of wind and thus becoming increasingly complex and abstract. His photograms encompass an abstract, oneiric space that we cannot easily reference, for it is openly ambiguous, hovering somewhere between the dream and the waking moment, superluminal and indeterminate yet strangely local. His photograms never alienate the eye that would assimilate them. They only entice, interrogate, and gather us into their uncharted spaces as willing captives to his poetics of hypertrophied vision. Onomatopoeic in their formal beauty, they transport us effortlessly to uncharted galaxies ordinarily beyond our ken. Whether images of snow-covered landscapes, photographed directly in strong sunlight, or the evidentiary bioluminescence of fireflies caught on photographic flypaper in the dead of night as they seek to couple and multiply, the finished works demarcate the fine line between the visible and the invisible, what is seen and what is unseen, the perceptible and the imperceptible.

In his earlier series, Rising, Flomen referenced the light of the sun and reflected light on snow in the creation of ambiguous tableaux that frustrated easy identification even while seducing the eye and mind with their beauty and indeterminacy. In his firefly-inspired works, he has moved on to a purely organic interior light suggestive of life, gestation, survival – and self-knowledge.

As Peter Sibbald Brown once wrote, “In this latest work, Michael Flomen presents an anonymous wilderness of magnificent ambient beauty – an atmospheric space without specific representational form. We become involved – steeped in the dreams of Seurat, Turner, Rothko; submerged in the light absorbing surface of Thoreau’s pond, and confronting the ‘eternal silence of these infinite spaces’ as the seventeenth century writer philosopher Pascal described the heavens while peering through Galileo’s telescope.”4 This is a fitting tribute to Flomen’s accomplishment, for, whether with solitary snowflake or firefly taillight, Flomen has taken nature’s fingerprints and imprinted them for all to see on simple photographic paper, bringing us into close proximity with the writing in the Book of Nature by holding up his own prosaic but telling mirror to it.

It would be no exaggeration to state that Flomen the photographer without a camera is an unabashed fabulist. If that suggests the making of fictions, well, Flomen has created some lovely fictions out of nature’s own whole-cloth handiwork, bounty, and progeny. In this respect, his work calls to mind an earlier pioneer of photography, Frederick Sommer, and we sense that the aesthetic impulse is as central to his existence as it was to that of the great (and sadly deceased) master. And his work shares a similar transformative, alchemy-driven compulsion to create works of art never seen before.

The works in the Bain Mathieu exhibition specifically recall for me Sommer’s images of smoke on cellophane and glass supports. In Golden Apples (1961), Sommer conjured up ethereal genies from the smoke-fraught residue the way that Flomen evokes unknowable terrain in works such as Breakthrough (2005) and Site (2004) and, for that matter, all the works that chronicle the mating dance of fireflies. Both photographers seize upon the unforeseen and run with the ineffable and bring into play a vast array of possible worlds.

It should be no surprise that the lightning traceries of fireflies’ seductions move us still. It is interesting to note that the unique light in question is generated by male fireflies eager to mate. They flash patterns of light to females who signal in response from hideaways in or near the ground. When the male sights the female’s reciprocal flash he continues signalling and heads toward her at full throttle. They trace out one another’s location through a rhythmic series of flashes, and mate. The luminescent tango of this mating ritual results in luminous hoops in Flomen’s photographs that the optic is enjoined to jump through with alacrity.

Like the male firefly of the species Photinus pyralis, Michael Flomen seduces the eyes wide open – and with the recorded light given off by fireflies during their abdominal flashes. The bioluminescent remnants of the “glow worms” and “lightning bugs” that populate Flomen’s photograms with wild abandon are integers of the ineffable – and unlikely emissaries of wholesale aesthetic truth.

The Aztecs used the term firefly metaphorically, meaning a spark of knowledge in a world of ignorance or darkness, and this understanding is perfectly in keeping with the luminosity of Flomen’s photographic work, for the latter is truly a beacon of light that keeps flashing at us whenever we become too jaded and indifferent in negotiating the deep and difficult waters of contemporary art.

2 Frederick Sommer, Aperture 10, no. 4 (1962), quoted in The Art of Frederick Sommer: Photography, Drawing, Collage (Frederick and Frances Sommer Foundation, Distributed by Yale University Press, New Haven, 2005), p. 50.

3 Elizabeth Bishop, “Over 2,000 Illustrations and a Complete Concordance,” in The Complete Poems 1927–1979 (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1984).

4 Peter Sibbald Brown, “Introduction,” in Michael Flomen, Still Life Draped Stone: The Photographs of Michael Flomen (Paget Press, 1984).

Michael Flomen lives and works in Montreal. His concrete approach to photography results in works that define the limits of representation, at the very threshold of abstraction. Since the late 1970s, his work has been frequently exhibited in Canada, the United States, and elsewhere. He is represented by the Hasted Hunt Gallery in New York, Diana Lowenstein Fine Arts in Miami, Thérèse Dion in Montreal, and the Artcore Gallery in Toronto.

James D. Campbell is a writer on art and independent curator based in Montreal. The author of over a hundred books and catalogues on art and artists, Campbell contributes frequently to art periodicals such as BorderCrossings, Parachute, Canadian Art, and Etc. He has taught history of photography at the University of Ottawa.