[Fall 2006]

Toronto

May 1 – 31, 2006

The CONTACT Toronto Photography Festival’s tenth-anniversary theme was “Imaging a Global Culture,” a reasonable choice for a festival that, like the city that hosts it, likes to underscore perspectives from a range of locales, customs and ethnicities. The theme also has an optimistic, ingenuous ring to it, a possible throwback to CONTACT’s mid-1990s beginnings – to the days when we couldn’t, for instance, take a picture of a cat with a cell phone and email it to a friend overseas (and then, of course, delete it), all in a matter of minutes. Indeed, one wonders if we really, in 2006, need a photography festival to herald the global reach of images when we have digital access to tens of thousands of them every day.

Yet it is in the nature of CONTACT not simply to provide access to images, but to ask viewers to dwell on their conceptual weight – on their heft and mystery. In this respect, the festival, and all gallery showings of photographs for that matter, are still beholden to photographic theory of yore, especially to that classic 1970s Barthes-cum-Sontag prescription: that the photograph is paradoxical, because it pretends to be solely denotative (i.e., instructional, representationally naked) but is in fact loaded with connotation (i.e., ideological impact that arrives through elements like captions, trick effects, and mise en scène). CONTACT’s theme last year, “Questioning the Truth in Photography,” was a call to see photographs in precisely this way.

Such dualism remains hardwired to the image’s form, though one wonders if the Internet has somewhat destabilized it, and, in turn, the relevance of events like CONTACT. Digital images want desperately to furnish unadulterated, unaestheticized proof – arguably more so, and with greater frequency, than any newspaper or magazine photograph of the past. An amateurish snapshot of a product on eBay wants only to convey its basic, material properties; amateurish snapshots of the interior of an apartment on the Toronto rental search engine View It want only to convey the layout of a space. That images on both of these web sites may not be fully trustworthy is, like everything else on the Net, a glib condition of their existence. Our exposure to more images has thus hardly stopped us from “questioning the truth in photography”; rather, it has caused us to become obsessed with veracity – often at the expense of more sophisticated, connotative readings. “True or false?” appears to be the only question we are now capable of asking in the face of images.

CONTACT’s success (or, its redeeming interest) this year was in its uncomfortable, multilayered engagement with this phenomenon. The festival’s deceptively simple theme promised access to different parts of the world via photographs: essentially, to the denotative. There were even little passport-style booklets available to guide viewers through the exhibition, as if a tour of the festival might offer the same edifying experience as an international romp. Yet CONTACT’s exhibitions did not escape the connotative. In fact, its two outstanding feature shows – Imaging a Shattering Earth at Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art and Unembedded at Lennox Contemporary (both of which, in an ironic twist, could be accessed in modified versions online) – faced significant struggles in their respective quests for bald, far-reaching truths.

In some measure, Claude Baillargeon’s curator’s statement for Imaging a Shattering Earth, a project developed by the College of Arts and Sciences at Oakland University, Rochester, Michigan, for its Environmental Explorations program, posits the photograph as a window. The show’s official goal is to bring together photographers – big names such as Ed Burtynsky, Emmit Gowin, and John Pfahl – to elucidate the problem of environmental destruction. Baillargeon tells us he would like Imaging to “foster a collective process of soul-searching” by having it draw attention to “the reckless stewardship of our planet.”

The exhibit brings viewers, in turn, to sites that have become almost unthinkably surreal because of their degradation under corporate exploitation. Images of clear-cut forests, industrial waste sites, and dried-up lakes provide shocking examples of the extent to which greed has quashed nature’s magnificence. John Ganis’s work is especially admonishing: his Site of a Federal Timber Sale, Willamette National Forest, Oregon and Alaska Pipeline, North of Valdez, Alaska are unforgivingly bleak – the natural world figured as humanity’s crack den.

But Ganis’s work stands apart in Imaging. Burtynsky, Gowin, and Pfahl all offer stunningly subjective renderings of a ravaged Mother Earth: they match the manipulated land that they depict with their own manipulations. Beauty, more often than not, is the end result. Much has been written about this effect in the work of Burtynsky, who also employs the sublime, an idea that he lifted from the tradition of landscape painting (notably of the Romantic, nineteenth-century kind); in Imaging, his Bao Steel, Shanghai, China (a.k.a. Bao Steel #8) may show a mill that turns out a literally sickening amount of pollution, but it has the impressive appearance of a lost, ancient city – the coal mounds look like black ziggurats, the distant smoke stacks like obelisks.

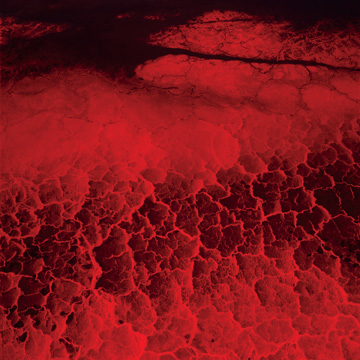

And so if Imaging’s sole purpose is to move us to revulsion and, accordingly, to polemical action, it doesn’t quite come off. Are we actually supposed to feel fear and indignation when looking at David Maisel’s gorgeous no. 9273-8, a photograph of the toxic Owens (Dry) Lake in California that, with its swirling red veins, resembles an expressionist painting? If photography has political power in Imaging, it is dependent on the connotative effect of captions – that is, of text. What is seen is not enough. As an object, the Maisel photograph merely gives us lines and vibrant colour (the work’s numeric title, moreover, betrays nothing). The image must be shaped by words, and by other works in the show (like Ganis’s, which more clearly denote environmental crisis), in order to trigger the “soul searching” that Baillargeon intends. Yet Imaging is not an exhibit of press photos, a fact that jars its curatorial agenda. One yearns to appreciate the loveliness of these images – all of which declare themselves as high art – but wonders, after reading the text that guides the show, if that is allowed.

Loveliness was certainly not allowed at Unembedded, Lennox Contemporary’s grueling show about the war in Iraq, which featured four photographers not officially sanctioned by, or “embedded” with, the U.S. Army. A show of this sort makes an implicit, and potentially dangerous, promise of authenticity – that is, these are images that other people aren’t showing you. Consequently, Unembedded is committed to careful, strict denotation: to minimizing, as much as possible, the various ideological treatments that the mainstream media is accused of foisting on photos – which includes suppressing them as much as it does girding them with editorial bias.

What is immediately noticeable about the show, then, is its lack of distinctive titles and, at times, captions: photographs are organized by places and dates only (e.g., Baghdad, 02/05/05). A handful of quotations, in enlarged, adhesive lettering, are visible above the photos; one reads, “War wounds are always multiple wounds … It’s not as simple as a bullet,” a doctor’s statement that affirms the show, in the most general sense, as anti-war or, more accurately, as anti-violence (who could deny such a statement?). Moreover, the work of the four photographers – Kael Alford, Thorne Anderson, Rita Leistner and Ghaith Abdul-Ahad, the only Iraqi of the bunch – is characteristic only to a point. Photos are rarely organized by who took them; rather by incident or subject, heightening Unembedded’s anonymous, reportage-oriented tone (there is one grouping of night scenes, for instance).

“Unembedded” radiates strife. Barthes’s idea in Image-Music-Text of trauma being the sole thing that can traverse the trappings of the connotative is, arguably, proven here. Kael Alford’s Baghdad, 04/26/03, which shows a mother and her blood-covered boy, is predictably unbearable. Yet one of the most remarkable moments of the exhibition – Rita Leistner’s series of photos taken in Baghdad’s Al Rashad mental asylum, a place ransacked by American tanks and, in turn, by looters during the invasion – does not show corpses or mortar-round explosions. Leistner’s focus, as it is with her images of Kurdish separatist guerrillas, is on women. Here, trauma suffuses faces; events may be unseen, but the psychological stains soak right through.

Another of Leistner’s Al Rashad photographs is of an inmate, in profile, passively seated on a chair while above her, in a cage, a television broadcasts a speech by American general Richard Myers. The woman is oblivious to Myers’ address – the no doubt vague content of which, one presumes, is barely reaching her in her current, distressed state. This is not a simple, denotative scene; it is about emotional and political containment, and about messages not doing their jobs. Similarly, a show such as Unembedded cannot do what we might expect it to; it cannot reach us unfiltered; no image can. And yet what these images capture is irrefutably dire. That we would turn away from them, or choose instead to point our fingers toward their slight formal contrivances, seems a belligerent luxury – we are, after all, nothing like that woman under the television set in Al Rashad. We are on the other side of the photograph.

David Balzer writes for eye Weekly in Toronto and has contributed to Canadian Art, Cinema Scope, Maisonneuve, and cv ciel variable.