[Winter 2006-2007]

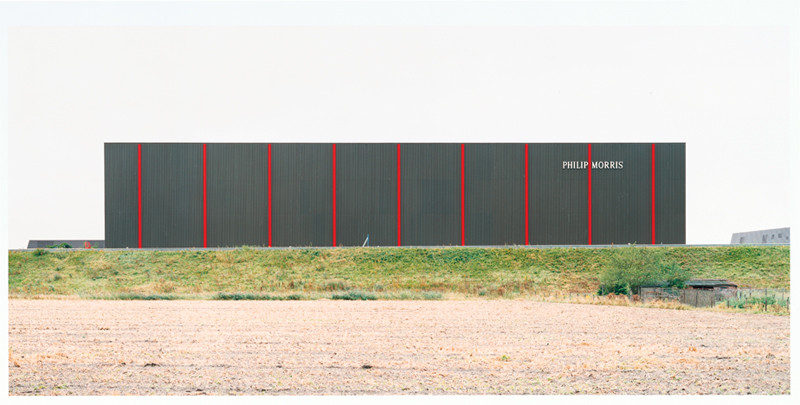

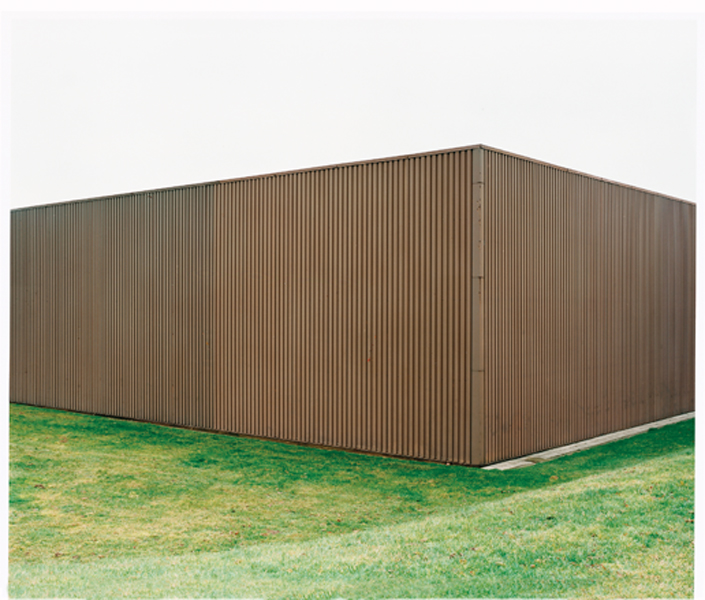

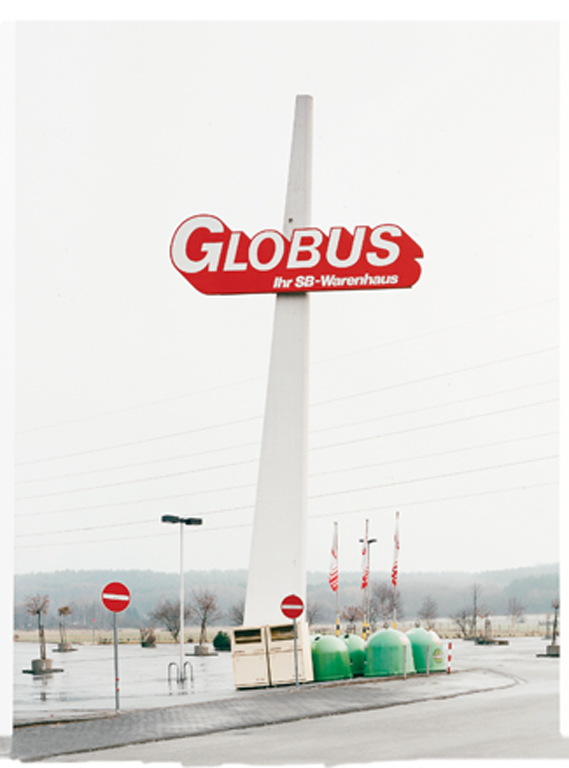

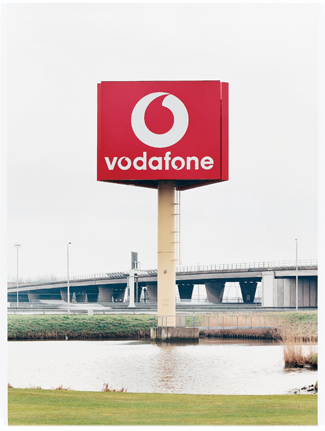

Cologne-based photographer Frank Breuer is a virtuoso of profuse emptiness. His photographs of the bleak but strangely beautiful warehouses and of the logo-bearing, corporate, pylon-like signs that often stand nearby seem largely emptied of discursive, annotative meaning. Because both the warehouses and the emptied sign-structures that are his subject offer no internal articulation, they are essentially scale-less, possessing temporality rather than interiority, and having more to do with duration, extension, and proliferation than with architecture or idea. This leads them toward a role as extrapolated minimalist objects: constant, indivisible, and, being spectacle-free (in the Debordian sense), paradoxically neutral, though imbued with the grace of presentness.

by Gary Michael Dault

He has photographed the generic warehouses, and other architecturally under-articulated buildings (and structures, such as aggregations of industrial containers), that he has found there with the kind of care that Berenice Abbott lavished in the 1930s upon the skyscrapers of New York,1 and with the precision with which Lewis Baltz indexed American tract houses and industrial parks in the early 1970s.

Breuer, like a number of other now well-known “new topographic” photographers of the last decade and a half, studied in Düsseldorf with Bernd and Hilla Becher. “The Becher students, Candida Hofer, Thomas Struth, Thomas Ruff, Andreas Gursky, and others,” writes Holger Liebs, in an essay titled “The Same Returns: The Tradition of Documentary Photography,” “have captured new levels of artificiality in urban zones that are rapidly succumbing to facelessness, like the man without qualities.”2

In addition to photographing bleak but strangely beautiful warehouses – structures without qualities – Breuer studiously documents the towering, sculpture-like signs that, bearing corporate logos, the bloodless, glacial props for consumer products, punctuate the post-industrial landscape. These logo-centric towers stand alone, proclaiming whatever their often enigmatic, design-compressed word-shapes are supposed to proclaim, or, erected near to the low-lying warehouse buildings and container stacks whose presence and meaning they appear to note and furnish, act as markers, which generate and carry post-industrial – and post-linguistic – utterances. These pylon-like structures, crisply if hermetically designed, and photographed by Breuer in high, almost participatory focus, tend to announce without signifying, thus giving new meaning to the term “empty signs.”

What are these mute warehouses, anonymous stacks of containers and signs that, despite the banality that they clearly embody, nevertheless can be seen to possess – at least in Breuer’s hands – a both compelling and unsettling fascination?

Presumably there are factories somewhere that still manufacture things, but we tend to lose track of where they are (they exist somewhere in that nostalgia-imbued tract of para-experience that Baudrillard and Eco called hyper-reality). Rather, we live someplace on the diadem of consumer goods, the trajectories of our desires leading us back not to reveries of the forge-or-factory wellsprings of our material dreams (where are things made?), but merely to the all-important sites of their stockpiling, their archiving, their holding places and distribution centres (where are things kept?). Production, in other words, has been, if not replaced by, at least occluded by distribution.

These ostensibly characterless warehouse buildings of Breuer’s, with their faceless facades, stretch across passages of banal landscape like giganticized minimalist sculptures by Robert Morris or Carl Andre. In fact, it feels as if they are not so much built on their sites as deposited there, guided into alighting on these evacuated locales delicately, weightlessly. For these warehouses, built as carapaces, as rectangular membranes, seem as vast and light as balloons, not so much constructed upon the ground as somehow tethered to it, like those huge, city-spanning domes that Buckminster Fuller used to posit that generated more lift than they did mass.

What are they? They are big, low spaces (which, by the way, is how Robert Venturi began his description of Las Vegas gambling casinos in Learning From Las Vegas).3 They are, as Breuer himself has described them, in an artist’s statement for Feigen Contemporary (New York, 2001), “industrial system constructions”: industrial spaces covered in monochrome sheet metal, or factories made of pre-cast concrete components. These entities are not so much architected as engineered (the infamous short-circuit of design-build), “propelled,” to use Breuer’s useful word, by computer-assisted design and production programs to the point where “these modular buildings seem to stretch out endlessly and grow ever larger without reference to familiar human proportions.” Breuer cannily identifies the space-inhabiting spacelessness of his structures when he notes, in his artist’s statement, that:

The formal quality of their undefined size may be captured through photography, since it is itself a medium of variable size. The monumental dimensions of the constructed logo or captioned industrial spaces may be reduced once again to the familiar size of a want ad in a newspaper. Irritation, which is brought into focus by the logo’s flat, two-dimensional imagery in interplay with the less familiar landscape context that related to the usual reception context, interests me.

Why are these structures not merely grotesque, then, in their epic emptiness; why not dehumanizing in their disaffection from human scale? How can we contain their state of absence, and re-parse the denial of continuity and conductivity in them that everywhere rebuffs us?

It was Henri Bergson who called disorder merely an order that we cannot see, and I surmise that the obverse is equally true: that order is merely a disorder that we cannot see. As viewers of Breuer’s extremely orderly photographs, we must remain, with him, entirely outside of the warehouses, factories, and containers that make up his works, witnesses only to the morphological imperatives that deliver the structure’s interior to its exterior. Who knows (who cares?) what is stacked and housed – or, if it is a factory, engendered – within these unenlightening, deadpan walls? What we see is constructed implacability. One of the paradoxes operating within the monolithic structures that Breuer photographs rests on the fact that no matter what is contained within one of these near-buildings, its interior will always be essentially interchangeable with its exterior: each is a kind of rhomboidal Möbius strip.4

What is beautiful, moving (is anything beautiful, moving?), about these Breuer-indexed structures? Well, there is a stirring nullity about them that is like an intake of breath. Because these cost-efficient, hyper-conceived industrial buildings have no articulation, architecturally speaking, they therefore offer no inner clausal subordination or subdivision-as-design – which means that they really do not possess or inhabit scale. Instead of interiority, they possess temporality: duration, extension, proliferation. Because, as design, as presences in the world, Breuer’s warehouses, signs, and containers are all centreless surface, they partake, along with certain classic works of minimalist sculpture (by Judd, Andre, Lewitt, Morris, Tony Smith) – and as extrapolations from them – qualities related less to architecture than to objecthood (the allusion is to Michael Fried’s groundbreaking essay “Art and Objecthood,” which first appeared in Artforum in 1967). What Fried had to say forty years ago about works of minimalist sculpture can now be said with equal validity about warehouses – as long as we acknowledge that we are talking morphology here and not sculptural desire. Speaking of the “endlessness and inexhaustibility” of a minimalist work’s shape and of the materials of which it is made, Fried quotes sculptor Robert Morris in his discussion of the ways, in such works, in which their material confronts the viewer in its literalness (all those uninflected metal walls which are walls which are walls . . .), in its absence of anything beyond itself (think about the receding landscapes in a Breuer, and the total disconnection from them effected by his chosen structures): “Characteristic of a gestalt,” Morris writes, “is that once it is established all the information about it, qua gestalt, is exhausted. . . . One is then both free of the shape and bound to it. Free or released because of the exhaustion of information about it, as shape, and bound to it because it remains constant and undivisible.”5

Presumably Breuer’s constant and indivisible ur-buildings, hermetic signs, and piles of containers are essentially spectacle-free – in the Debordian, Society-of-the-Spectacle sense – which is what lends them a blazing visual and sociological neutrality, their huge impassivities coming to us as inescapable and, indeed, as almost oceanic pauses: structure-as-hiatus. We are all literalists for most of our lives, notes Fried, and for that reason, he suggests, in structure, “presentness is grace.”6 Frank Breuer’s photographs of the post-industrial Other are composed of just such a benign and disorienting equivalence.

Two books about the work of Frank Breuer were recently released: Logos Warehouses Containers, Fiedler Contemporary, Cologne / Jousse Entreprise, Paris / schaden.com, Cologne, 2005; Poles, the Faulconer gallery, Grinnel, Iowa, 2006.

1 “The challenge for me has first been to see things as they are, whether a portrait, a city street, or a bouncing ball. In a word, I have tried to be objective. What I mean by objectivity is not the objectivity of a machine, but of a sensible human being with the mystery of personal selection at the heart of it. The second challenge has been to impose order onto the things seen and to supply the visual context and the intellectual framework – that to me is the art of photography.” – Berenice Abbott

2 Holger Liebs, “The Same Returns: The Tradition of Documentary Photography,” in Elizabeth Janus (ed.), Veronica’s Revenge: Contemporary Perspectives on Photography (Zurich: Scalo, 1998), p. 106.

3 Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and Steven Izenour, Learning From Las Vegas (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1977), p. 50.

4 “In Nausea Sartre said ‘a circle is not absurd, it is clearly explained by the rotation of a straight line around one of its extremities. But neither does it exist.’” Toby Mussman, “Literalness and the Infinite,” in Gregory Battcock (ed.), Minimalism: A Critical Anthology (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1968), p. 248.

5 Michael Fried, “Art and Objecthood,” in Battcock, Minimalism, p. 143.

6 Ibid., p. 147.

Frank Breuer studied photography at the University of Applied Sciences in Cologne and at the Düsseldorf Academy of Arts, where he received the graduation certificate and the distinction of master student under Bernd Becher. Breuer received fellowships and grants from the Stiftung Kunst und Kultur NRW, Düsseldorf and the Wüstenrot Stiftung, Ludwigsburg. His photographs are in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; the Photographic Collection of the Museum Folkwang, Essen; the ZKM Karlsruhe; and the Manfred Heiting Collection, Amsterdam. Frank Breuer is represented by Fiedler Contemporary, Cologne.

Toronto writer, art critic, and painter Gary Michael Dault is the author, or co-author, of ten books. His art review column appears each Saturday in The Globe and Mail.